by Terry L. Mingee, RDH

The mouth-body connection, or focal sepsis theory, is proved through numerous published research articles and books on the subject. Plaque is one of the major causative agents in periodontal diseases. Periodontal diseases are the direct precursor of physical diseases associated with heart diseases; stroke; pre-term, low birth-weight babies; chronic degenerative diseases; pneumonia; uncontrolled diabetes; and many other metastatic infections.

Since the early 1900s, there has been investigation into the theory of mouth-to-body infection. The most common theory of that time was devised by Dr. William Hunter in 1909. His "Focal Infection Theory" stated that dental (septic) infection was the most important cause of, and complication of, medical diseases. The concept was highly regarded in what is now known as the "Focal Infection Era in Dentistry," from 1909 to 1937. It was believed that microorganisms spread from distant chronically infected sites, such as the mouth, to target organs. The most common treatment was the therapeutic edentulation of the infected individual.

Effects of an unhealthy mouth

To have a thorough understanding of the concept of focal infection, the cause of the initial infection should be reviewed. Research shows that the body's reaction to infection — whether it's a mild irritation or a full-blown infection with bone and tooth loss — could be life-threatening. As mentioned above, a host of metastatic infections have been linked back to the mouth, specifically periodontal disease.

The percentage of people in the United States who actually visited the dentist on a regular basis was 73 percent in 1997. In the year 2000, it fell to 67.9 percent. What people don't realize is that these regular preventive visits may help save their lives. Therefore, it is of utmost importance that everyone practices the prevention of dental disease. The healthier the mouth, the healthier the body will be. By simply flossing alone, one can expect to extend their life expectancy by at least six years. In fact, one's oral health is indivisible from total health. As a case in point, signs and symptoms of many potentially life-threatening diseases appear in the mouth first, when they are most treatable. Brushing and flossing one's teeth are at the core of prevention. Through current research, the importance of prevention and oral health will be established. And it all starts by removing the bacterial plaque and other materials attached to the tooth by brushing and flossing daily.

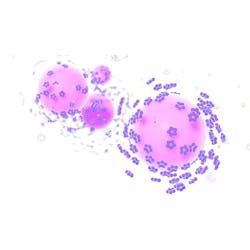

More than 300 different species of organisms are found within the periodontal pockets around the teeth. However, the ones that are closely allied to periodontal disease can be divided into two major types. The first type consists of densely packed, colonized, and colonizing microorganisms, which grow on and attach to the tooth. This type may be supragingival or subgingival. The second type of bacterial plaque is "free floating" or loosely attached subgingiva between the teeth and gingiva.

The attached bacteria is not easily removed by forceful water spray, but is readily removed by other mechanical means. Some of these bacteria produce byproducts of toxins or enzymes that can irritate the tissues that support the teeth. These byproducts can damage the attachment of the gingiva, other periodontal tissues, and the bone of the affected teeth.

Food debris, unless impacted between the teeth or within periodontal pockets, is usually removed by action of the oral musculature and saliva, or as a result of rinsing or brushing. That which is impacted between teeth and in periodontal pockets is of concern. Food lodged into sites of periodontal infection may stimulate the body's defense mechanisms to get rid of the invading material. A worse infection may result and accelerate the already present infection.

Lastly, calcified plaque, or calculus, resides supra- and sub-gingivally on the teeth. Because of its rough and porous surface, calculus irritates the gingiva. Also, because of the surface texture, bacterial plaque is able to form a soft layer over calculus to further irritate the gingiva. Approximately one third of all adults have calculus.

The book, Periodontology for the Dental Hygienist, states that after plaque and calculus accumulate and reside on the teeth for more than 10 to 21 days, gingival infection results. The longer the plaque and calculus are on the teeth, the more harmful they become. It is estimated that 80 percent of American adults currently have some form of periodontal disease.

Most of the early onset and rapidly progressive forms of periodontitis are associated with systemic disease. Severe periodontitis has been observed in blood dyscrasias and in primary neutrophil disorders. Acquired immunodeficiency diseases also have been associated with rapidly advancing forms of periodontitis. Generally, the systemic diseases for gingivitis can be referred to for periodontitis as well.

Periodontal diseases are no longer regarded as infections to which everyone is equally susceptible. Because some groups are more "at risk" than others for destructive periodontal disease, current research is rapidly identifying and determining the relative importance of these risk factors. Some known risk factors for developing disease are:

• Smoking — Smoking is one of the most significant risk factors associated with the development of periodontal disease. Smoking can also lower the success rate of many treatments.

• Diabetes — People with diabetes are at higher risk for developing infections, including periodontal disease.

• Stress — Research shows that stress can make it more difficult for the body to fight infection, including periodontal disease.

• Medications — Some drugs, such as antidepressants, contraceptives, and some heart medicines, can affect oral health because they lessen the flow of saliva.

• Poor nutrition — A poor diet, especially one low in calcium, has been shown to lower a person's resistance to gum disease.

• Illnesses — Diseases such as cancer, AIDS, and other viral infections and their treatments can affect the health of the gums.

• Genetic susceptibility — Some people are more prone to periodontal diseases.

Surgeon General's report

When a patient has any of the previously discussed periodontal infections, or believes that he or she may have symptoms of periodontal infections, a dental provider and regular medical doctor should be seen as soon as possible. The reason to seek medical and dental attention was stated in a report by the Surgeon General, Donna E. Shalala, in 1997.

In her report, Oral Health in America: A Report by the Surgeon General, she states, "The major message of this Surgeon General's report is that oral health is essential to the general health and well-being of all Americans and can be achieved by all Americans ... What amounts to 'a silent epidemic' of oral diseases is affecting our most vulnerable citizens — poor children, the elderly, and many members of racial and ethnic minority groups ... The terms of oral health and general health should not be interpreted as separate entities. Oral health is integral to general health; this report provides important reminders that oral health means more than healthy teeth and that you cannot be healthy without oral health."

Also in the report were praises for many successful preventive measures adopted by communities, individuals, and oral health professionals that resulted in marked improvements in the nation's oral and dental health.

Ms. Shalala said, "We are fortunate that additional disease prevention and health promotion measures exist for dental caries and for many other oral diseases and disorders — measures that can be used by individuals, health care providers, and communities."

A thorough oral examination can detect signs of nutritional deficiencies, as well as a number of systemic diseases, including microbial infections, immune disorders, injuries, and some cancers. She reported that new research is pointing to associations between chronic oral infections and heart and lung diseases, stroke, and low birth-weight and premature births.

The following will explore the associations or connections between systemic diseases and periodontal diseases.

• Periodontal disease and heart disease — Current studies are finding an association between periodontal disease and heart disease. In one study, men with extensive periodontal disease had over a four-fold greater risk for heart disease than men without periodontal disease. Some experts believe that, in people with periodontitis, normal oral activities, such as brushing and chewing, can cause tiny injuries that release bacteria into the blood stream. The bacteria that cause periodontitis may stimulate factors that cause blood clots and other proteins that contribute to a higher risk for heart disease. In some rare cases, periodontal bacteria can cause an infection in the lining or valves of the heart called infective endocarditis. The condition is more likely to occur in valves that are already injured or abnormal.

A study by Loesche et al. was performed on 320 U.S. veterans in a convenience sample to assess the relationships between oral health and systemic disease among older people. This resulted in a cross-sectional study confirming that a statistically significant association exists between a diagnosis of coronary heart disease and certain oral health parameters, such as the number of missing teeth, plaque benzoyl-DL-arginine-naphthylamide test scores, salivary levels of Streptococcus sanguis, and complaints of xerostomia. The oral parameters in these subjects were independent of, and more strongly associated with, coronary heart disease than were recognized risk factors such as serum cholesterol levels, body mass index, diabetes and smoking status.

Genco, Offenbacher and Beck performed statistical research of the current data from various studies and surmised that there was a moderate association — but not a causal relationship — between periodontal disease and heart disease. They had researched the data and found six longitudinal studies with positive relationships between periodontal disease and heart disease, compared to three that found no relationship at all. Some of the research found that the odds of having a history of a heart attack increased with the severity of periodontal disease. Some data support the notion that specific pathogenic bacteria found in cases of periodontal disease also may be associated with heart attack. Another sample of data was readjusted to account for the inability to quantify severity of periodontal disease and still came out with an affirmative relationship regarding a tooth lost to periodontal disease and incidence of coronary heart disease.

The follow-up of this particular group 15 years later showed a relationship between periodontal disease and subsequent heart disease. People with periodontal disease are one and a half to two times more likely to suffer a fatal heart attack than a healthy person. There are ongoing studies to establish a correlation between periodontal disease and heart disease that will result in a clearer picture; however, it would be safe to say there is a very strong relationship between the two thus far.

• Periodontal disease and stroke — In the research of data by Genco et al., there also was a remark that stood out above the rest: "The studies that focused on stroke appear to demonstrate stronger relationships with periodontal disease ..."

Armin J. Grau, MD, reported that as the natural barrier between the tooth and gingiva erodes, bacteria from the inflammation and infection might be able to enter the bloodstream. Those bacteria can increase plaque buildup in the arteries, leading to hardening of the arteries and stroke.

In one study, one-third more people who had a stroke were found to have severe periodontitis, compared to the control group. The odds for this group tended to increase when compared with other stroke risks such as previous stroke, high blood pressure, diabetes, current and previous smoking and even childhood socioeconomic status. The author of this study also found that people with severe gingival disease were twice as likely to have the type of stroke brought on by clots than people with good oral health. They surmised that the relationship was stronger between periodontal disease and stroke than with heart disease. People with periodontal disease are three times more likely to suffer a stroke than healthy people.

• Periodontal disease and low birth-weight babies — In some studies, oral bacteria have also been associated with pre-term, low birth-weight babies. According to Dr. Drisko, the presence of antibodies to certain oral bacteria identified in the amniotic fluid and fetal cord blood suggest that mothers with periodontal disease may be six to seven times more likely to have a pre-term, low birth-weight baby.

In addition to the antibodies in amniotic fluid, Dr. Drisko reports that microbes in the female lower genital tract may ascend to produce a pelvic infection or inflammation that may result in a portion of pre-term births. Current research is underway to determine if treating the periodontitis of pregnant women will decrease the number of pre-term, low birth-weight babies. Current research states that mothers of prematurely born babies were seven times more likely to have advanced periodontal disease than mothers whose babies were normal weight at birth.

• Periodontal disease and chronic degenerative diseases — There have been findings that people with periodontitis appear to share genetically determined risk factors with several other chronic degenerative diseases such as ulcerative colitis, juvenile arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus.

Recent research points to specific genetic markers associated with increased production of the pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin-1 and TNF as strong indicators of susceptibility to severe periodontitis. This recent finding could lead to early identification of people at most risk for severe periodontal disease and initiation of appropriate therapeutic interventions.

• Periodontal disease and diabetes — People with diabetes have periodontal disease more often than people without diabetes. The destructive inflammatory processes that define periodontal disease are closely intertwined with diabetes. Persons with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus [NIDDM] are three times more likely to develop periodontal disease than non-diabetic individuals. An increased risk for destructive periodontal disease also holds for persons with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus [IDDM].

A new finding is that there is evidence that a history of chronic periodontal disease can disrupt diabetic control, suggesting that periodontal infections may have systemic repercussions. Currently, investigators are examining the interplay between periodontal infection and metabolic control. These studies have come out with some information already yielding some evidence that chronic infections, such as periodontal disease, worsen glycemic control and that eliminating these infections could enhance metabolic control in persons with diabetes.

• Periodontal disease and other metastatic infections — In a lecture by William Morgan, DDS, at Great Lakes, Ill., there were listed many of the additional infections that are recorded with correlation between periodontal diseases and physical diseases: Bacterial endocarditis, myocarditis, prosthetic joint infection, paraspinal abscess with paraplegia, toxic shock in Down Syndrome, febrile episodes in lymphoma patients, death from sepsis of dental origin, multiple brain abscesses, arthritis, uveitis, glomerulonephritis, meningitis, Bell's palsy, fevers of "unknown" origin, leukocyte dysfunction, and gastritis.

Paul Luepke, DDS, in a continuing education seminar in Great Lakes, Ill. in 2001, listed even more metastatic infections, including peptic ulcers, appendicitis, bacterial pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and osteopenia.

• Periodontal disease and osteoporosis — Recently, another disease correlated to periodontal disease has come to light — osteoporosis. Numerous studies have been conducted on the relationships between the two diseases. While a relationship between the two events in older Americans has been demonstrated, the researchers have not yet discovered whether they both happen because of age, or if there is a periodontal infection produced because of osteoporosis.

Oral hygiene and prevention

Now that there is an understanding of the relationships between periodontal diseases and diseases of the body, the concept of oral hygiene should be of interest. The mouth-body connection should be the motivating factor toward the goal of total oral health. An important fact to remember in attaining oral health is that mouth care depends on brushing and flossing techniques more than on the use of any specific product.

Removing plaque and food debris from between the teeth is just as important as it is on the other brushed surfaces of the teeth. Flossing began in the early 1800s. Parmly, in 1819, recommended that waxed silken thread be used for flossing the teeth.

He stated, "Silken thread which, though simple, is most important. It is to be passed through interstices of the teeth, between their necks and the arches of the gingiva, to dislodge that irritating matter which no brush can remove and which is the real source of disease."

The objective of flossing the teeth is to remove plaque and debris that adhere to the teeth, restorations, orthodontic appliances, fixed prostheses and pontics, gingiva in the interproximal spaces and around implants. It aids in identifying the presence of subgingival calculus deposits, overhanging restorations, or interproximal carious lesions. It also reduces gingival bleeding, which is a sign of periodontal disease. Lastly, it may be used as a vehicle for the application of polishing or chemotherapeutic agents in interproximal and subgingival areas.

Michael Roizen, MD, states that his research has found that flossing every day can reduce the burden of oral and systemic disease in percentages comparable to quitting smoking. He has also developed a system called RealAge. It is said that flossing regularly can increase a person's life expectancy by six years. Lee Fitzgerald, DDS, states, "Flossing has now been shown to add years to your life."

Research shows that with brushing and flossing of the teeth and gingival tissues, one will improve not only oral health, but physical health as well. The information reviewed about focal sepsis, or the mouth-body connection, is just the tip of the iceberg when researching physical diseases and their correlation to periodontal diseases. Until there are more results from the ongoing research, one must assume that there is a strong connection between the mouth and body and, therefore, care should be taken to maintain a clean and healthy mouth for the benefit of overall health.

Terry Mingee, RDH, graduated from Parkland Community College in Champaign, Ill., in 1987.He has been practicing at Great Lakes Naval Base for 14 years.He is enrolled full-time at Southern Illinois University, earning a bachelor's degree in health care management. He has also taught clinical skills at College of Lake County.His plans include teaching and working toward a master's in public health.

Women and younger females are at higher risk and have many risk factors of their own. The rapid hormonal changes that women go through on a monthly cycle can make the gingival tissues more sensitive and make it easier to develop gingivitis. Also, during the cycle, the female may notice lesions, canker sores and swollen salivary glands. Many women notice no changes at all during this time.

Through the teen years, the production of the hormones progesterone and estrogen exaggerate the way the gingiva reacts to the irritants of plaque. The gingiva may become red, tender, swollen, and likely to bleed easily during tooth brushing. Usually, after the teen years, there is a decrease in the inflammation and bleeding of the tissues.

During pregnancy, the hormone levels of the body increase dramatically. Gingivitis is especially common during the second to eighth months of pregnancy, and may cause red, puffy or tender gums that tend to bleed when they are brushed. This particular sensitivity is caused by an increase in the progesterone level of the body.

Inflamed gingiva is seen also in women who take oral contraceptives. Prolonged use of birth control pills may cause the gingiva to turn red, bleed and swell in response to any local irritants in the mouth, such as food or plaque.

Finally, during menopause, the female may notice several changes, including some that occur in the mouth. These may include a burning sensation, altered taste sensations, a decrease in salivary flow that can result in dry mouth, and greater sensitivity to hot and cold foods and drinks.

If women already have periodontal diseases of some kind, they may find their problem worsening during any of these situations.

ReferencesAmerican Dental Association. (1997). Scaling and root planing: Treating periodontal diseases [Brochure]. Chicago, IL: Author.American Dental Association. (1998). Gum disease: Are you at risk? [Brochure]. Chicago, IL: Author.American Dental Association. (1998). Taking care of your teeth and gums [Brochure]. Chicago, IL: Author.American Dental Association. (1998). Women and gum disease [Brochure]. Chicago, IL: Author.American Dental Association. (2000). Periodontal diseases: A major cause of tooth loss [Brochure]. Chicago, IL: Author.American Dental Association. (2000). Spread the word: Periodontal disease care is for everyone [Brochure]. Chicago, IL: Author.American Dental Association. (2000, July). For the dental patient [Electric version]. Journal of the American Dental Association, 131, 1095.American Dental Association. (2002, May). Women and periodontal disease [Electric version]. Journal of the American Dental Association, 133, 671.American Dental Hygienists' Association. (2002). The future of oral health: Trends and issues. Retrieved September 11, 2002, from http://www.adha.org/profissues/future/page1.html..The Centers for Disease Control. (2002, March 12). Dental visits: Percentage of people who visited the dentist or dental clinic within the past year. Retrieved September 14, 2002, from http://www2.cdc.gov/nohss/ListV.asp?qkey=2.Fedi, P. F., Verano, A.R., & Gray, J.L. (2000). The periodontic syllabus (3rd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.Fitzgerald, L. (n.d.). Preventive dentistry: Flossing. Retrieved September 10, 2002, from http://www. Dallasdentist.com/Fitzgerald/pages/jpages/prevention-patients.html.Floss.com (1999). Flossing: A new secret to good health? Retrieved September 10, 2002, from http://www.floss.com/flossing.htm.Floss.com (2000, December). Periodontal disease and its effect on your heart. Retrieved September 10, 2002, from http://www.floss.com/periodontal_disease_and_its_effe.htm.Genco, R., Offenbacher, S., & Beck, J. (2002, June). Periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease: Epidemiology and possible mechanisms. Journal of the American Dental Association, 133, 144-210.Harris, N. O., & Garcia-Goday, F. (1999). Primary preventive dentistry (5th ed.). Stamford, CT: A Simon & Schuster Company.Healtheon/WebMD (2000). Flossing and brushing may be food for your brain: Further evidence that dental disease leads to stroke. Retrieved September 10, 2002, from http://www.webmd.lycos.com/content/article/1728.55046.Hester-Seckman, C. (2002, July). Osteoporosis: The periodontal connection. RDH, 46-48.Hodges, K. (1998). Concepts in non-surgical periodontal therapy. Albany, NY: Delmar Publishers. IL: Author.Loesche, W.J., Schork, A., Terpenning, M.S., Chen, Y.M., Dominguez, B.L., & Grossmaan, N. (1998, March). Assessing the relationship between dental disease and coronary heart disease in elderly U.S. Veterans. Journal of the American Dental Association, 129(3), 30-311.Lupke, P. (2001). The mouth and body connection: A discussion by CDR Paul Lupke. Paper presented at the continuing education session at the Great Lakes Dental Society Meeting, Great Lakes, IL.Morgan, M. (2000). Periodontics and systemic illness. Paper presented at the continuing education session at the Great Lakes Dental Society Meeting, Great Lakes, IL.National Institute of Dental & Craniofacial Research. (n.d.). Periodontal (gum) disease. Retrieved September 14, 2002, from http://www.nidcr.nih.gov.National Institute of Diabetic Research. (n.d.). Oral opportunistic infections: Links to systemic diseases. Retrieved September 14, 2002, from http://www.nidr.nih.gov/spetrum/nidcr2/2textsec3.htm.Naval Graduate Dental School (1975). Periodontics syllabus, U. S. Navy Dental Corps. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.Nevada Dental Hygienists' Association. (2000). Surgeon general's report on oral health highlights: Talking points. Retrieved September 10, 2002 from, http://www.nvdha.org/surgeon_general.html.Perry, A. P., Beemsterboer, P. L., & Taggert, E. J. (1996). Periodontology for the dental hygienist. Philadelphia, PA: W. B. Saunders Company.Scott, B (2002). ADHA media release: ADHA encourages flossing for a healthy life. Retrieved September 10, 2002, from http://www.adha.org/media/releases/020402_flossing.htm.University of Alabama at Birmingham. (1998). Floss daily to preserve your teeth and gums. Retrieved September 10, 2002, from http://www.health.uab.edu/ show.asp?durki=8368.Walthius, M.. (1996-1997). Want some life saving advice? Ask a registered dental hygienist [Electronic brochure]. Retrieved September 11, 2002, from http://www.dentalhygienistusa.com/brochure1.htm.