The Tongue

by Dianne Glasscoe, RDH, BS

The tongue — what a marvel of the human creation! That strange little 3-ounce piece of flesh may be small, but it does marvelous and wonderful things for us!

Our tongue is one tough worker! Beyond tasting, the tongue is a major part of several functions of life, including speaking, eating, swallowing, sucking, and drinking. The tongue is also important for tooth and tissue health, kissing, sweeping the mouth for food debris and other particles (such as hairs), warming the air during mouth-breathing, and oral play (for instance, poking the tongue out and waggling it about for fun). Dental clinicians often wrestle with large, untamable tongues that make isolation of particular teeth difficult.

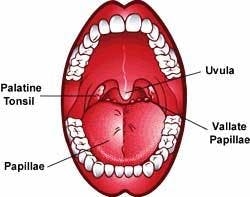

The tongue is a small organ comprised of muscle, fat, connective tissue, and nerves. It is covered with a mucous membrane and small projections called papillae that give it a rough texture. There are three major types of papillae — two in front and one in back. At the front of the tongue are fungiform and filiform papillae. At the back of the tongue are the vallate papillae. They are large and round, and there are about eight to 12 of them. Papillae help grip food and move it around while you chew.

People are born with about 10,000 taste buds. As a person ages, some of the taste buds die. This may explain why our taste seems to change as we age. Taste organs are scattered over the entire surface of the papillae, with large numbers concentrated on the circumvallate papillae, toward the middle of the tongue. Taste buds can detect sweet, sour, bitter, and salty flavors. Recently, scientists found a new kind of taste bud that responds to the taste of MSG, a chemical food additive. They call this flavor umami.

A well-documented phenomenon during the decades of manned space flight — but one that's not completely understood — is that food tastes differently in space. Some astronauts have reported that food tastes bland while they are in orbit. Others find that, while they are in space, they can't stand something that is one of their favorite foods on Earth, or that they really enjoy eating something they ordinarily wouldn't touch. Still others say that they can't tell any difference at all.

The tongue's muscular versatility

Relatively short at birth, the tongue grows longer, and thinner at the tip, as we get older. Although the tongues of some birds, amphibians, reptiles, and mammals have been studied, we are far from understanding the relationship between muscle structure and function within tongues. Gross tongue motion caused by contraction of any individual muscle is dependent on the activity of surrounding muscles. Interworkings of muscles allow the tongue to bend, protrude, retrude, shorten, widen, depress, curve, and move laterally and in a circular motion. The tongue has two kinds of muscles: intrinsic and extrinsic. Intrinsic muscles change the shape of the tongue. Extrinsic muscles move the tongue around in the oral and pharyngeal cavities.

The intrinsic muscles are:

• Superior

• Longitudinal

• Inferior Longitudinal

• Transverse Vertical

The extrinsic muscles are:

• Genioglossus

• Styloglossus

• Palatoglossus

• Hyoglossus

• Speaking — The most important articulator for speech production is undoubtedly the tongue. Without the teeth, lips, and the roof of the mouth, the tongue would not be able to form sounds to make words. Sounds are differentiated, among other things, by position of the tongue related to the palate, and by the curvature and contracture of the tongue. During speech, the amazing range of movements the tongue can make include tip-elevation, grooving, and protrusion. Different tongue shapes cause us to pronounce words differently. Consonants and vowels show different characteristics. For vowels, the entire tongue matters as well as its curvature, while for consonants, it is mainly the points of contact between the tongue and the palate or teeth that matter. For consonants, the tongue touches the palate with more tension.1

Can you imagine trying to talk without a tongue? To give you an idea what that would be like, try holding your tongue down with a tongue depressor and start talking. The sounds you make are mostly unintelligible.

• Eating — Tongue movement is important during mastication. It helps place food onto the teeth repetitively for crushing, and then aids in formation of the food bolus. After material is formed into a cohesive bolus, it is held against the hard palate or at the floor of the mouth in front of the tongue.

During normal swallowing, the tongue undergoes a sequence of muscular deformations. The ingested bolus is initially contained in a groove-like depression in the middle dorsal surface of the tongue (early accommodation). This surface depression is then translated in a posterior direction until the bolus comes to rest at the posterior edge of the tongue (late accommodation). Finally, the oral stage of the swallow is concluded by the rapid clearance of the bolus retrograde into the oropharynx at speeds approaching 100 cm per second.

Swallowing physiology involves a number of complex actions involving muscles and nerves. The oral cavity is rich in mechanical (touch, pressure) receptors on the tongue, teeth, gums, and palate. Sensory information from these receptors is transmitted via cranial nerve V (Trigeminal) to brainstem centers responsible for swallowing coordination. The oral phase is initiated when the tongue begins posterior movement of the bolus. The central groove is formed in the tongue to act as a chute for the bolus.

As the oral stage ends, the pharyngeal stage begins when the swallowing reflex is triggered. The swallow reflex is triggered when the leading edge of the bolus passes the anterior faucal arch. Sensory receptors in the oropharynx and tongue are stimulated by the bolus, sending sensory information to the brainstem and cortex.

The esophageal phase begins when the bolus enters the upper esophagus. Esophageal peristalsis pushes the bolus inferiorly, and once the bolus reaches the lower esophageal sphincter, it opens, allowing the bolus to pass into the stomach.

Babies have been observed swallowing at the tenth to eleventh week of gestation. Suckling ability (anterior-posterior tongue movement) can be seen at 18 to 24 weeks of gestation. Most healthy fetuses are able to suckle and swallow well enough to sustain nutritional needs by eight to eight and a half months of gestation.

Diseases of the tongue

• Thrush — This infection is caused by the fungus Candida albicans, and is manifested by white, slightly raised patches on the mucous membrane of the tongue, mouth, and throat. The mucous membrane beneath the patches is usually raw and bleeding. The overgrowth of this fungus results when the balance in the normal oral microbe population is disturbed by antibiotic therapy or disease. It occurs most frequently in infants, in adults suffering from chronic illnesses, in the debilitated, in the immunosuppressed, and in individuals on long-term antibiotic, corticosteroid, or antineoplastic therapy. It is often an early symptom of HIV infection. Treatment is with antifungal drugs such as nystatin.

• Hairy tongue — A hairy tongue is due to a profuse overgrowth of a particular type of taste bud — the filiform papillae — which gives the appearance of thick fur on the tongue. This can result from:

• Antibiotic treatment

• Fever

• Excessive use of mouthwashes, which liberate oxygen from the mouth environment

• Reduction in salivary flow due to problems with the salivary glands

Brown papillae are usually due to tobacco staining or overgrowth of a particular type of chromogenic bacteria.

There are no symptoms associated with a hairy tongue. Treatment is of the underlying cause, such as stopping antibiotics or mouthwashes or dealing with the salivary gland problems.

• Hairy leukoplakia — Hairy leukoplakia is one of the most common HIV-associated oral signs. It is a white, corrugated, or "hairy" coating on the lateral borders of the tongue. Unlike thrush, it is not easily scraped off. It is painless, but patients occasionally complain of its appearance and texture. It is caused by the body's reaction to the Epstein-Barr virus (responsible for mononucleosis), and can be eliminated with a viral antibiotic called Acyclovir.

• Lichen planus of the tongue — Lichen planus affects between 1 to 2 percent of the population, most of whom are middle-aged women. The condition is less common in the very young and the very old. The lesions are found on the skin, genitals, and in the mouth.

Lichen planus of the mouth most commonly affects the inside of the cheeks, gums, and tongue. Oral lichen planus is more difficult to treat and typically lasts longer than skin lichen planus. Fortunately, many cases of lichen planus of the mouth cause minimal problems. About one in five people who have oral lichen planus also have skin lichen planus.

No one knows what causes lichen planus, although some experts suspect that it is an abnormal immune reaction following a viral infection, probably aggravated by stress. Occasionally, lichen planus in the mouth appears to be an allergic reaction to medications, filling material, dental hygiene products, chewing gum, or candy.

Symptoms can appear suddenly, or they may gradually develop, usually on the arms or legs. The lesions on the skin may be preceded by a dryness and metallic taste or burning in the mouth.

Lichen planus in the mouth occurs in six different forms with a variety of symptoms, appearing as lacy-white streaks, white plaques, or eroded ulcers. Often the gums are affected, so that the surface of the gum peels off, leaving the gums red and raw.

Using milder toothpastes instead of tartar control products also seems to lessen the number of ulcers and makes them less sensitive.

• Geographic tongue — Geographic tongue (benign migratory glossitis) is a benign condition that occurs in up to 3 percent of the general population. Most often, it is asymptomatic; however, some patients report increased sensitivity to hot and spicy foods. The etiology and the pathogenesis are still poorly understood. The condition affects males and females and is noted to be more prominent in adults than in children.

Classically, it appears as an area of erythema, with atrophy of the filiform papillae of the tongue, surrounded by a white, hyperkeratotic border. The patient often reports spontaneous resolution of the lesion in one area, with the return of normal tongue architecture, only to have another lesion appear in a different location of the tongue. Lesion activity may wax and wane over time, and patients are occasionally free of lesions. If lesions occur at other mucosal sites, the condition is termed erythema migrans.

• Human papillomavirus — Oral warts can occur anywhere in the mouth, including the tongue. The causative agent is the human papillomavirus (HPV). These growths generally are not painful and can be ignored unless they interfere with appearance or function. It is estimated that 40 million Americans are infected with one or more of the 80 strains of HPV. HPV has been implicated in some oral cancers and is contagious.

• Tongue cancers — The most common cancers of the tongue are squamous cell cancers. The exact cause of tongue cancer is unknown. However, the following lifestyle factors may be related:

• Smoking cigarettes, cigars, or a pipe

• Use of chewing tobacco, snuff, or other tobacco products

• Heavy alcohol consumption

Symptoms of tongue cancer may include:

• Skin lesion, lump, or ulcer on the tongue

• Difficulty swallowing

• Mouth sores

• Numbness or difficulty moving the tongue

• Change in speech (due to inability to move the tongue over the teeth when speaking)

Life without a tongue

Some cancers of the tongue require either a partial or total glossectomy. Factors influencing prosthetic prognosis of restoring the tongue include the presence or absence of teeth and the type of procedure that is combined with the glossectomy (for example, mandibulectomy, palatectomy, radiation therapy). Patients with partial glossectomy (usually less than 50 percent of the tongue removed) suffer minimal functional impairment and require no prosthetic intervention. Removal of more than 50 percent of the tongue requires construction of a palatal or lingual augmentation prosthesis.

Total glossectomy causes a large oral cavity, loss of verbal communication, and pooling of saliva and liquid. Patients with a total glossectomy require a total tongue prosthesis. In dentulous patients, such a prosthesis can be attached to the mandibular teeth through a lower partial denture.

In edentulous patients, tongue prosthesis can be retained to either a mandibular or maxillary denture. Common problems associated with tongue prosthesis include lack of salivary control and loss of ability to maneuver food from the buccal vestibule. Therefore, it is best to fabricate two prosthetic tongues, one for swallowing and one for speech.

A typical prosthetic tongue for speech is flat with wide anterior elevation, which aids in articulation of anterior lingual alveolar sounds (for example, "t," "d"). The typical prosthetic tongue also has a posterior elevation, which aids in production of posterior lingual alveolar sounds (for example, "k," "g") and helps shape the oral cavity for improved vowel productions.

The tongue prosthesis for swallowing is made with a trough in its posterior slope to guide the food bolus into the oropharynx. A speech pathologist and, when necessary, a nutritionist should monitor all patients who have a glossectomy.

All American English vowels (except retroflexed vowels) are articulated with virtually perfect identifiability with the use of a solid tongue prosthesis fixed on the lower teeth. Spring-loaded rotatable prostheses are devised for consonantal articulations.

Head and neck defects often must be replaced with soft tissue and/or bone from other areas of the body. Significant loss of soft tissue requires flaps of sufficient bulk to adequately reconstruct the defect. Proper flap design and tailoring of the flap to fit a certain tissue defect results in optimal functional and cosmetic outcomes.

Rectus abdominis free tissue transfer allows for transfer of a large vascularized segment of skin and muscle from the abdominal wall to its intended recipient site. Patients in whom other flaps would be too thin can benefit from this flap. As a muscle-only flap, it has become indispensable for reconstruction following skull base surgery. As a myocutaneous flap, it is particularly suitable for reconstructing partial and total glossectomy defects.

As dental clinicians, we must be diligent in performing thorough tongue examinations on all patients. Discovering and identifying early lesions on or under the tongue can and does save lives. Tongue examination is an essential step in delivering high quality care to our trusting patients.

The tongue is a small organ that is often taken for granted. However, it works day and night, makes life more enjoyable, and even stirs our passion. It sends us a sharp, quick message when we accidentally bite it or burn it with hot food. It has been described in historical literature as untamable. Like a large ship steered by a small rudder, the tongue is a small part of the body but boasts great things!

The appearance of the tongue is often an indication of body health; a pinkish-red color is normal. In impairment of digestion and in certain feverish diseases, a yellowish coating forms.

To doctors who practice traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), the tongue is an important point of interest. The tongue is one of the key examination sites in TCM as practiced in China and other parts of the world.

The TCM doctor wants to see the tongue, its shape, the color of both the tongue and its coating, its texture, how it moves — regardless of the patient's illness or lack of illness. Tongues can vary with coatings that are thin, thick, white, yellow, red, pale, dark, gray, black, greasy, etc., and with the tongue body or muscle running into shades of red, blue, purple and black.

A large study of cancer patients tracked the connection between tongue appearance and various cancers. The literature on the subject suggests that the tongue changes with tumor size. "When the tumor grows, the tongue gets more bluish [and has] more textural changes."2 Reading tongues is a complex matter, and disagreement on the significance of tongue appearance can occur from TCM expert to expert.

• Nutritional deficiencies — Vitamin B12 (cyanocobalamin) The most serious manifestation of B12 deficiency is pernicious anemia. Pernicious anemia leads to a general muscular weakness and signs of deterioration of the central nervous system. Skin pallor, heart palpitation, and eventually more severe heart disturbances are also symptoms, as are a sore, red, inflamed tongue that eventually becomes smooth and glazed.

Niacin (nicotinic acid) Niacin is important in tissue respiration, proper brain function, the nervous system, and healthy skin. Symptoms of mild deficiencies include irritability, anxiety, abdominal pain, dry and scaly patches on the skin, and a burning sensation in the tongue. As the deficiency becomes more severe, the tongue will become inflamed and raw, and skin patches become cracked and fissured.

• Tongue jewelry — Oral piercing is a cultural fad seen primarily among young people. Oral piercing can cause pain, swelling, infection, drooling, taste loss, scarring, chipped teeth, and tooth loss. Since body piercing is not a regulated industry, sterilization methods can come into question. People being pierced take great risks in acquiring diseases transmitted through improperly sterilized instruments.

Dianne D. Glasscoe, RDH, BS, is a professional speaker, writer, and consultant to dental practices across the United States. She is CEO of Professional Dental Management, based in Frederick, Md. To contact Glasscoe for speaking or consulting, call (301) 874-5240 or email [email protected]. Visit her Web site at www.professionaldentalmgmt. com.

References1 Modeling and Animating the Human Tongue During Speech Production, by Catherine Pelachaud, University of PA)

2 12,448 Cases of the Clinical Observation of Cancer Patients' Tongues, Journal of Oncology [in Chinese], Vol. 7, No. 3, 1987