‘Red flags’ to prevent medical emergencies

by JoAnn R. Gurenlian, RDH, PhD, and Frieda Atherton Pickett, RDH, MS

The medical history is a tool that is used in dental and dental hygiene practices as an effective means of preventing a medical emergency. Careful interviewing, listening, and communicating with clients can provide clues to potential problems that may occur in the dental office setting. Although some emergencies are unexpected, many that occur in clinical practice can be predicted by gathering adequate information and analyzing it in terms of risk assessment. Certain items on a medical history, if answered “yes,” require further evaluation. These are red flags or areas that warrant additional information.

The purpose of this two-part series is to highlight some of the red flags that a medical history reveals, and to provide information on preventing subsequent medical emergencies or disease transmission associated with those positive responses. The 2007 American Dental Association health history form is used as the prototype for identifying questions that can elicit red flag responses.

Screening questions for active tuberculosis

Ask patients, “Do you have any of the following diseases or problems?”

● Active tuberculosis (TB)

● Persistent cough for more than three weeks

● Cough that produces blood

● Exposure to anyone with TB

“If your answer is ‘yes’ to any of the four items above, please stop and return this form to the receptionist.”

Since elective oral health care is contraindicated in the client with active TB disease, it is important to pursue further questioning to determine the nature of positive responses to these questions. When the client responds affirmatively on any of these items, investigate to determine if the client has active TB infection. Ask these follow-up questions:

■ Have you seen a physician about this persistent cough?

■ Have you been tested recently for exposure to tuberculosis with a skin test?

■ Do you wake up during the night from sweating?

■ Have you recently had unexplained weight loss?

■ Do you know anyone who has had TB?

■ Has anyone in your family or a friend or coworker been diagnosed with tuberculosis?

These questions give clinicians an opportunity to identify a client who may be contagious prior to beginning oral procedures. When active TB is suspected, isolate the client within the facility to perform follow-up questioning. Then refer the client for medical evaluation. A medical consultation form should request the physician to notify the office whether or not the client has active TB. Clients who do not have active TB can receive oral health care. For clients with active TB, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends three criteria for non-infection that should be verified on the signed medical clearance form before oral health care is provided:

▲ The client is not in the coughing stage.

▲ The client has taken three consecutive negative sputum smears on three separate days.

▲ The client has taken effective anti-TB medications for at least three weeks.1

Stress-related emergencies

Ask patients, “Have you had any problems associated with previous dental treatment? If so, explain.”

Case reports suggest individuals who have experienced a negative dental experience are more likely to have emergency situations during an appointment.2 This question may identify a client at risk for syncope (fainting) or hyperventilation, two common stress-related medical emergencies that occur during dental and dental hygiene treatment. Both conditions are often associated with anxiety and fear. Dental procedures themselves, experiencing or anticipating pain, the sight of blood, and receiving an injection of local anesthesia are predisposing factors that may result in a stress-related emergency.

Stress-reduction strategies can be used to prevent syncope. Gain the confidence and trust of the client, and help him or her to relax. Talk with the client about personal interests to serve as a distracter, ensure adequate pain control, use nitrous oxide conscious sedation, and prescribe an antianxiety medication.3,4

Loss of consciousness in the dental office, unrelated to anxiety, may also occur when the client is placed in an upright position. When seated in the dental chair for a long time, blood can pool in the extremities and venous blood return to the heart is reduced. This leads to vasodilation and hypotension (referred to as postural hypotension) with inability of the cardiovascular system to push oxygenated blood to the brain. This type of syncopal episode can be prevented. Recognize the signs leading to unconsciousness, place the client in a prone position, and have the client lift the feet and push on a stable surface (such as your hands). This positioning and management promotes skeletal muscle activation and venous return to the heart, increased blood leaving the heart, and oxygenated blood flow to the brain.

Hyperventilation is characterized by rapid breathing and results in excessive loss of carbon dioxide and inspiration of too much oxygen. A previous history of hyperventilation during dental treatment is a clue to anticipate this emergency. The stress-reduction strategies noted above can be used to prevent this condition.

Change in general health

Ask patients, “Has there been any change in your general health within the past year?”

A positive response to changes in general health requires follow-up questions to investigate the change and needed medical care. A change in health may represent an improvement; i.e., when one has recovered from cancer therapy. However, if the client reports a worsening of general health, the clinician must determine how the condition and/or treatment may influence oral health care. A medical consult may be indicated to determine the appropriateness of dental treatment and additional medical care, such as the need for premedication. For example, a client may report a recent diagnosis of hypertension. If extensive dental treatment is indicated and vital signs reveal abnormal values (i.e., blood pressure ≥180/110 or pulse ≤50 bpm or ≥120 bpm), medical evaluation should occur before treatment to determine whether the client can withstand the stress of the dental procedure and if a vasoconstrictor limitation is necessary.5-7

Taking prescription medications

Ask patients, “Are you taking or have you recently taken any prescription or over-the-counter medicines? If so, please list all, including vitamins, natural or herbal preparations, and/or diet supplements.”

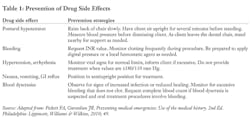

This question gives the clinician an opportunity to correlate medications used with general health. In some cases, clients forget to report all of their health conditions, but will note medications prescribed for a medical condition. In addition, this question prompts the dentist or hygienist to investigate drug effects, indications for use, adverse drug events, and side effects. Drug side effects associated with a risk for medical emergency or the necessity for modified treatment include postural hypotension; anticoagulant effect or increased bleeding; hypertension; arrhythmia; nausea, vomiting, or other GI complaints; and blood dyscrasias such as leukopenia, neutropenia, or thrombocytopenia.

Any medication your client takes should be investigated using a drug reference text before initiating treatment. It is important to learn the action of the drug and how that might affect treatment, the dose the client is taking, side effects related to oral changes, interactions between the client’s drug and drugs that might be prescribed related to oral health care, and dental treatment considerations.4 Postural hypotension is one of the most common emergency situations and is most frequently related to taking a drug that lowers blood pressure, coupled with placing the client in the supine position for a long period of time.

In some cases, the client cannot recall all medications used or the details related to medication management. Send the health history form to a new client’s home in advance of his or her appointment. This gives the client an opportunity to list the proper names of their medications, dosage, and use.

One potential problem is when a client presents for treatment and reports taking warfarin, an anticoagulant that requires a monthly lab test known as International Normalized Ratio (INR) to determine the risk for increased bleeding. The client may not know why this medication was prescribed, the INR, or the date of the most recent lab visit. It is essential to determine this information prior to providing treatment to identify the risk for uncontrolled bleeding. The clinician should request the most recent INR data. If the INR is too high (over 3.5), elective oral health procedures may need to be delayed. If the INR cannot be recalled or if the physician lowered the dose of the anticoagulant at the last lab result, this might pose an increased risk for excess bleeding.4,5 Other prevention strategies for managing potential medical emergencies associated with medication use appear in Table 1.

Allergic reactions

Ask patients, “Are you allergic to or have you had a reaction to the following?”

▼ Local anesthetics

▼ Aspirin

▼ Penicillin, antibiotics

▼ Barbiturates, sedatives, sleeping pills

▼ Sulfa drugs

▼ Codeine or other narcotics

▼ Metals

▼ Latex (rubber)

▼ Iodine

▼ Hay fever or seasonal allergy

▼ Animals

▼ Food

▼ Other

This question involves a variety of substances sometimes used as part of oral health care that have been associated with an allergic response. Hay fever or seasonal allergy and allergies to animals and foods are included because clients with a positive history of any allergy are at an increased risk for having an allergy to products used as part of dental care. The length of time between being exposed to an allergic substance and the development of signs of allergy can alert the health-care provider to the risk of life-threatening emergency conditions. Typically, the more rapidly allergic signs develop, the more dangerous the situation. Mild signs of allergy include skin rash, erythema, hives, urticaria, or stomatitis. Severe signs of allergy include bronchoconstriction, asphyxiation, dyspnea, reduction of blood pressure, and cardiovascular collapse (anaphylaxis).

Follow-up questions to evaluate allergic reaction potential include:

- What specific agent (i.e., local anesthetic, antibiotic, narcotic drug, latex, etc.) caused your reaction?

- What were your symptoms? (used to determine true allergy vs. drug side effect)

- How rapidly did the signs develop?

- Are you having any symptoms today (i.e., seasonal allergies)?

- Are you currently taking any medications for seasonal allergies, pain, infection, etc.?

- How was your allergic reaction treated?

Oral health-care professionals must document in the dental record any allergies to drugs or products likely to be used in the dental or dental hygiene appointment, and use of these products must be avoided during treatment. Clients who report multiple allergies are at a significant risk for allergy to products used during treatment and must be monitored for signs of an acute allergic reaction. Keep an emergency kit containing 1:1000 epinephrine and regularly update the kit to ensure that drugs are not out-of-date.

Conclusion

This article reviewed some of the red flags clinicians need to address when reviewing the medical history. In the August issue of RDH, we will discuss additional concerns that require follow-up to prevent medical emergencies from occurring in dental and dental hygiene practice settings.

JoAnn R. Gurenlian, RDH, PhD, is president of Gurenlian & Associates, and provides consulting services and continuing-education programs to health-care providers. She is a visiting scholar at Capella University and vice president of the International Federation of Dental Hygienists.

Frieda Atherton Pickett, RDH, MS, is a former associate professor at the Caruth School of Dental Hygiene, Baylor College of Dentistry, as well as an author and lecturer.

References

1. CDC. Core Curriculum on Tuberculosis. 4th Ed. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for HIV, STD, and TB Prevention, Division of Tuberculosis Elimination, 2000. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/th/pubs/corecurr/default.htm. Accessed Sept. 17, 2009.

2. Elter JR, Strauss RP, Beck JD. Assessing dental anxiety, dental care use and oral status in older adults. J Am Dent Assoc 1997; 128(5):591-597.

3. Lahmann C, et al. Brief relaxation versus music distraction in the treatment of dental anxiety. J Am Dent Assoc 2008; 139(3):317-324.

4. Pickett FA, Gurenlian JR. Preventing medical emergencies: Use of the medical history. 2nd Ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2010; 34-35, 48, 52.

5. Little JW, Falace DA, Miller CS, Rhodus NL. Dental management of the medically compromised patient. 7th Ed. St. Louis, Mo.: Mosby Elsevier, 2008; 10-13, 64, 417.

6. Chobanian AV, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. JAMA 2003; 289:2560-2578.

7. Terezhalmy G. Clinical Medicine in Therapeutics. In: Pickett F, Terezhalmy G, eds. Dental Drug Reference with Clinical Implications. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2010; 124.