Cement-associated peri-implantitis

by Lynne Slim, RDH, BSDH, MSDH

I've heard it said that cement-associated peri-implantitis is dentistry's dirty little secret. It doesn't surprise me that excess cement is positively associated with peri-implantitis. Knowing what we do about biofilms and indwelling medical device biofilm-related infections, it's logical to assume that excess cement around an implant-retained restoration will cause serious infection. Dental implants are indwelling medical devices, and not teeth! Many bloodstream infections and urinary tract infections are associated with implanted medical devices and, in most cases, are biofilm associated.1 The most effective strategy for treating these sometimes life-threatening infections may be removal of the biofilm-contaminated device.1

In general, the rougher and more hydrophobic the material, such as implant cement, the greater the rate and extent of attachment by microorganisms.1 Once microorganisms irreversibly attach and grow on a surface such as cement, they are resistant to antimicrobial agents and host defenses.1

---------------------------------------------------------------------

Other articles by Slim:

Is household bleach an effective biofilm killer

---------------------------------------------------------------------

In reviewing this topic, I received a plethora of great information from a variety of master clinicians, including hygienists. I will mention some of them and give you some of their best advice for dealing with this growing problem. I won't be discussing techniques to eliminate or control flow of cement, but will focus instead on what is pertinent to the practicing RDH whose focus is on maintaining dental implant health.

The number of dental implants placed in the United States increased tenfold between 1983 and 2002; there are now over 700,000 implants inserted annually.2 This is expected to increase at a sustained annual growth of 9.4% over the next several years.2 Implant dentistry has grown in popularity, and many clinicians have simplified their implant-retained restorations to closely resemble conventional crown-and-bridge procedures.3

Not all implant clinicians receive equal training, and gone are the days when they were being exclusively placed by periodontists or oral surgeons with surgical specialty training.

The incidence of peri-implantitis is growing. According to the American Academy of Periodontology, there is a variation in the reported prevalence of peri-implantitis, which ranges from 6.61% over a 9- to 14-year period in one study, to 23% during 10 years of observation in another study, as well as 36.6% in a third study with an average 8.4 years of loading.4

The etiology of cement-associated peri-implantitis may be multifactorial. Like the movie, "It's Complicated," with a thick and twisting plot, so too are the etiologic factors associated with failing implants. According to Susan Wingrove, RDH, the majority of late failures of already integrated implants can be attributed to peri-implant infections and cement residue and only a small percentage of failures are due to occlusal overload.5

Peri-implantitis is a fairly new term, having first been introduced in the 1980s and modified in the 1990s to describe an inflammatory disease that results in loss of supporting bone.6 It is different intrinsically from peri-mucositis, which is reversible and limited to inflammation of mucosa around an implant, not bone.6 The general term peri-implantitis refers to any implant with varying degrees of bone loss if accompanied by probing depths ≥ 4 mm and bleeding, and/or purulent exudate on probing.6 Collectively, peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis are referred to as peri-implant disease.6

It is important to note that peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis are stand-alone entities with multifactorial etiologies, one of which is residual implant cement. The primary etiology of peri-implant disease is bacterial plaque/biofilm in a susceptible host, and this is the same etiology that initiates periodontitis. Cement is a biofilm-retentive factor that exacerbates this disease process.

Froum and Rosen have proposed the classification for peri-implantitis seen in Figure 1.

Dental hygienists might find this particular classification useful in documenting what they observe in terms of degree of severity for failing dental implants. Standardization by means of classification might also improve communication between dental team members such as RDHs who may be the first to recognize peri-implant inflammation.

I first read about the positive relationship between excess cement and peri-implant disease in a 2009 article about a prospective clinical endoscopic study, and this particular publication drew a lot of attention to this issue.7 Just as Löe provided evidence that dental plaque is the etiological factor for gingivitis in the 1960s, Wilson in 2009 drew attention to cement-associated peri-implantitis by exploring the relationship between excess dental cement and peri-implant disease (peri-mucositis and peri-implantitis) using a dental endoscope. In a private practice study, 39 patients with clinical and/or radiographic signs of peri-implant disease were studied over a five-year period.7 Excess cement was associated with signs of peri-implant disease in the majority (81%) of the cases. Clinical and endoscopic signs of peri-implant disease were absent in 74% of the test implants after the removal of excess cement.7

As implant dentistry has skyrocketed in popularity, many clinicians have attempted to simplify their protocols to more closely resemble conventional crown-and-bridge procedures.8 Cement implant prostheses have been added to more conventional screw-retained implant restorations for many reasons such as improved esthetics.

What some implant clinicians have been unaware of, however, is the biological and prosthetic differences between teeth and dental implants.5 In teeth, supracrestal connective tissue with an area of dense circular fibers attach to the tooth perpendicularly and may become mineralized within the cementum, resulting in a strong attachment to the tooth. In contrast, the connective tissue attachment in implants has fewer fiber bundles and their orientation tends to run parallel to the implant surface, resulting in less protection overall from invading pathogens.5

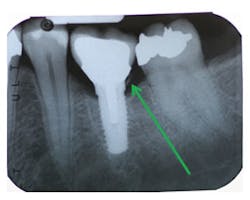

According to Present and Levine, many implant clinicians, for esthetic reasons, like to place margins of their implant restorations greater than 2 mm subgingivally.8 They emphasize that researchers have demonstrated that it is almost impossible to remove excess cement around implant restorations with subgingival margins greater than 1.5 mm.8 Radiographic examination doesn't always reveal remnants of cement, particularly on buccal/lingual surfaces.8 Levine reports that peri-mucositis can be observed from as early as six weeks to over nine years.

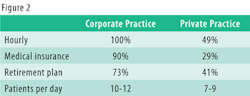

In writing about cement-associated peri-implantitis, I cannot possibly cover everything that's been written about factors affecting etiology, problems with various cements, or time frames of presentation of peri-mucositis or peri-implantitis. Instead, I focus on hygiene-related management issues (see Figure 2) that pertain to cement assessment. Keep in mind that the health of periodontal tissues is always dependent on properly designed restorations, and only with advanced study by implant clinicians can this growing problem be addressed.

The driving force behind the popularity of cemented implant crowns was to make the procedure more like cementing a crown on a tooth so that general dentists would not be intimidated by restoring implants. Other factors included improved esthetics as well as simplification of procedure. Keep in mind that screw loosening is no longer a reason not to place a screw-retained implant. It was a problem with very early implant screw designs but this problem was corrected many years ago. With screw-retained implants, excess cement is a nonissue. Abutments with visible margins are strongly recommended to avoid excess cement in the abutment/restoration complex and in peri-implant tissues. The deeper the position of the margin, the greater the amount of undetected cement.11

LYNNE SLIM, RDH, BSDH, MSDH, is an awardwinning writer who has published extensively in dental/dental hygiene journals. Lynne is the CEO of Perio C Dent, a dental practice management company that specializes in the incorporation of conservative periodontal therapy into the hygiene department of dental practices. Lynne is also the owner and moderator of the periotherapist yahoo group: www.yahoogroups.com/group/periotherapist. Lynne speaks on the topic of conservative periodontal therapy and other dental hygiene-related topics. She can be reached at [email protected] or www.periocdent.com.

References

1. http://cid.oxfordjournals.org/content/33/8/1387.full

2. http://www.nobelbiocare.com/Images/en/Vol2.1HaswellPart1IPUS_tcm261-33674.pdf

3. http://www.dentalaegis.com/cced/2013/06/techniques-to-control-or-avoid-cement-around-implant-retained-restorations

4. American Academy of Periodontology. Academy report: peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis: a current understanding of their diagnoses and clinical implications. 2013; 84(4): 436-443.

5. Wingrove S. (2013) Peri-implant therapy for the dental hygienist: clinical guide to maintenance and disease complications. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

6. Froum SJ, Rosen PS. A proposed classification for peri-implantitis. 2012 Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. Oct 2012; 32(5): 533-540.

7. Wilson T, Jr. The positive relationship between excess cement and peri-implant disease: a prospective clinical endoscopic study. J Periodontol. 2009; 80(9): 1388–1392.

8. Present S, Levine RA. Techniques to control or avoid cement around implant-retained restorations. Compendium. Jun 2013; 34(6): 432-437.

9. Linkevicius T et al. Does residual cement around implant-supported restorations cause peri-implant disease? A retrospective case analysis. Clin. Oral Impl. Res. 00, 2012, 1-6.

10. Lang NP, Berglundh T, Heitz-Mayfield LJ, Pjetursson BE, Salvi GE, Sanz M. Consensus statements and recommended clinical procedures regarding implant survival and complications. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2004; 19 Suppl:150-4.

11. Linkevicius T et al. The influence of the cementation margin position on the amount of undetected cement. A prospective clinical study. Clin Oral Implants Res 2013 Jan; 24(1): 71-76.

FIGURE 2: Excess cement assessment considerations for the RDH

1. Keep in mind that the time frame from initial signs of peri-implant disease (peri-mucositis or peri-implantitis) after cementation can range from as early as three to four months to nine years after delivery. Cement-related bone loss may occur very quickly or be delayed, and some patients may be resistant to peri-implantitis development for unknown reasons.

2. Read a variety of articles/books on this particular topic. See references for a much-needed new textbook by Susan S. Wingrove, RDH, and other great articles on the topic. The AAP report on peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis is very informative, and I strongly recommend it. You can read it on the AAP website, www.perio.org under Academy Statements.

3. Follow the AAP report in assessing peri-implant disease with emphasis on periodontal probing/exploring to look for signs of suppuration or cement residue. Blow air around the inflamed implant and explore carefully. If you have an endoscope, scope it thoroughly!

4. Monitoring implants is an important topic. Many doctors and RDHs are afraid of implants once restored. Implants need to be monitored with regular periodontal probing using plastic probes and regular radiographic examination. The signs of disease around an implant are similar to natural teeth including bleeding/suppuration upon probing, tissue redness, and increasing periodontal disease. This is why it is critical that soon after an implant is restored some baseline data needs to be established (radiograph and probing depths) so that changes can be monitored over time with comparison to this baseline data. In addition, monitor bone loss around an implant. Bone loss >2 mm means >2 mm from baseline bone levels after implant loading/restoration. Many implants lose bone to the first thread in the first year and then remain stable forever. So the >2 mm of bone loss is below the most recent level of stability/health.

5. Two pearls of wisdom from Wingrove:

a. Identification of bony lesions (facial, lingual, and proximal) due to peri-implantitis or cement-residue implantitis can be aided by cone-beam-computed tomography (CBCT) scanning.

b. For cement-retained implant restorations, cement residue is often found around the entire circumference of the implant, making early detection of cement residue critical.6

6. Implants with cement remnants in patients with a history of periodontitis may be more likely to develop peri-implantitis, compared with patients without a history of periodontal disease.9

7. Wingrove and Edie Shuman Gibson, RDH, recommend using dental tape (not a slippery floss type) to detect excess cement. Wingrove recommends inserting the floss below the contacts on both sides of the implant, wrapping the floss in a circle, crisscrossing in front and moving in a shoeshine motion in the peri-implant crevice, looking for frayed portions.5

8. Make note of what type of cement was used to lute the restoration and become familiar with the degree of opacity, potential corrosiveness, and ease of removal for various cements.5 Older and cheaper cements containing zinc can be more readily seen but some of the newer and more expensive cements cannot be seen and detected. The newer implant cements are harder to remove. Resin cement, according to Dr. R. A. Levine, is generally the culprit due to its thinness, inability to be seen on a radiograph, and similarity to subgingival calculus as biofilm magnets. Dr. Levine is recommending zinc-containing cements with a specific technique. (See reference No. 8.)

9. Identify what type of implant abutment was used and time frame since delivery of the abutment.5 In cemented implant crowns, custom abutments with supragingival margins are less susceptible to excess-cement associated peri-implantitis. Single-tooth custom abutments control the cement line and facilitate cement removal, according to Glenn J. Wolfinger, DMD, FACP. Dr. Levine emphasizes that cement in tissue depths greater than 1.5 mm should be avoided. He favors either a custom abutment that brings the cement line to a more coronal position or a screw-retained crown, which avoids the cement issue altogether.

10. RDHs must become familiar with evidence-based protocols for peri-implantitis treatment, and I strongly recommend reading the consensus statements by N. P. Lang et al., which include recommended clinical procedures for implant complications.10

11. Dental radiographs are not a reliable method for excess cement evaluation.11

Past RDH Issues