Synergy and the patient-provider relationship: The hygienist’s essential role in communication and treatment acceptance

By Ronald E. Goldstein, DDS, and Yemia A. White, RDH, BSDH

Editor’s Note:This article is part one of a three-part series submitted by the authors.The second and third parts are scheduled to appear in the January 2018 and February 2018 issues.

The role that each dental team member plays can positively or negatively influence patients’ perceptions of the practice, their trust in the providers, and their treatment acceptance. Synergy is defined as “the increased effectiveness that results when two or more people or businesses work together.”1 The relationship between the dentist and the dental hygienist, in particular, is one that requires a delicate balance of skill, communication, and collaboration to meet the patients’ needs.

Too many times, the newly hired hygienist and other team members are not given a thorough enough education into the dental practice’s goals and patient management procedures, which can lead to confusion and potential team failure. This symbiotic relationship must consist of mutual respect for one another as well as an understanding of expected clinical procedures, skills involved, ethical expectations, plus the psychological and social practices that each dentist expects. This series will concentrate on the strategies that play an important role in the essential relationship between the hygienist and the dentist.

The goals of the dental team

In the dental office, the dentist represents the captain, who leads the team in the direction that he or she believes is best. However, on every team, there are key positions that play critical roles in the overall success or failure of the group. In the dental office, the hygienist liaises between the dentist and patients to ensure that their specific needs are being addressed.

“Primary care dental teams are in a distinctive position to become actively engaged in promoting oral health equity, both for their own patients and the wider community. Dental teams get to know families and understand their lives in great detail through continuity of care, often over many years, and in some cases across generations of the same family.”2 With the right synergy between the dentist and the team, patient growth can expand exponentially through family and friend referrals, not to mention the power of social media and online reviews.

“Dentistry is a profession that has a twofold role: (1) to provide health-care service and (2) to make a profit as a business.”3 However, these are baseline roles, and from that, the dentist as team captain needs to set high expectations for its success in this competitive market. Beyond baseline roles, providers must be proactive in cultivating their patient-provider relationships. For example, calling a patient to let that person know the provider is behind schedule shows respect for the patient’s time. Remembering the names of a patient’s family members or the individual’s recent travels helps create a rapport that exceeds the one-dimensional professional relationship. Then, following through with patient service beyond the dental appointment, such as a courtesy call after treatment, displays a genuine concern for the patient. These subtle actions not only strengthen the patient-provider relationship, but they also help retain patients, contributing to a profitable business and increased referrals for the practice.

Dental hygienist: The essential partner

Ideally, the hygienist should be an extension of the dentist’s diagnostic and treatment concepts. This role can be more complicated in a multidoctor office where each dentist may diagnose differently. “Dental hygienists’ scope of practice is determined by state laws and state regulatory boards.”4 Generally speaking, hygienists provide prophylactic services, fluoride treatments, pit-and-fissure sealants, oral hygiene instructions, nutritional counseling, take dental radiographs and clinical photographs, and use the intraoral camera for patient education and as an aid in treatment acceptance. Additional responsibilities—such as administering local anesthetic, nitrous oxide, and laser application—vary from state to state as do supervision levels. However, since the hygienist spends so much more time examining each tooth as well as the changing stomatognathic system, he or she can be of immense help in letting the dentist know beforehand what may be a patient problem that needs attention.

“The traditional education of the dentist has placed great emphasis on developing a highly competent diagnostician and clinician, but it has often left a noticeable void in the area of practice management (and communication).”3 If there is no time to alert the dentist before the patient exam, ask a simple question such as, “Can you take a look at the distolingual of tooth No. 3?” This way, the hygienist is not referring to it as a problem. It also allows the dentist say, “I think it is OK for now; keep a watch on it,” or “Good finding; it is decay that needs attention,” etc.

Establishing a basic script that the hygienist and dentist use to communicate in front of the patient ensures that successful communication is implemented. The Academy of General Dentistry and the American Dental Hygienists’ Association define direct supervision as “the dentist needs to be present to provide services.” General supervision means “the dentist needs to authorize prior to services, but need not be present” and direct access means “the dental hygienist can provide services as he or she determines appropriate without specific authorization.”5 As dental offices incur staff turnover, it is important to make sure that streamlined communication remains in effect. A standard handbook created by the dentist and the team should establish expectations for protocol, communications, and standards across the board. This guidebook can certainly ease the transition for new staff members.

The new patient

Depending on state laws and practice protocols, new patient appointments may be scheduled according to a few scenarios. In the first scenario, the patient makes an appointment for a consultation with the dentist. The dentist and dental assistant see the new patient first to review medical information, discuss patient concerns, take radiographs and intraoral photos, if necessary, and formulate a treatment plan. The patient is then rescheduled for a future appointment with the hygienist (Figure 1).

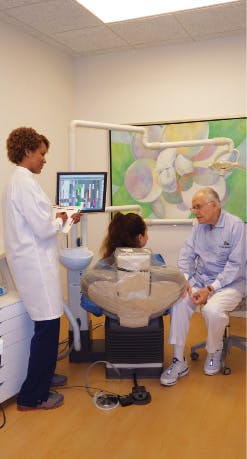

In the second scenario (Figure 2), the new patient asks for a prophylaxis appointment. In this situation, the dentist may see the patient first for an introduction, review of medical information, and brief clinical exam. The hygienist completes preventive services, and then the dentist returns to complete the comprehensive examination.

The last scenario is one in which the dental hygienist sees the patient first. The hygienist gathers pertinent information needed for a comprehensive evaluation, and renders hygiene services based on the patient’s needs. Afterwards, the dentist performs the comprehensive examination and answers any questions the patient may have.

The hygienist-patient relationship plays an important role in a patient’s decision to return for recurring appointments. Hygienists often spend more time with patients for preventive services than dentists do with patients for restorative treatment.

There are pros and cons in each scenario. For example, in the first, the dentist and assistant have an opportunity to establish a rapport with the patient. The patient may feel more comfortable asking the assistant questions, so the assistant can relay that information to the dentist beforehand. Also, if the dentist does an intraoral exam prior to hygiene, he or she has a better sense of the patient’s oral health and can consider that when treatment planning. Such a situation arises with a patient who gets considerable stain. After determining when the last prophylaxis had occurred, the dentist can better predict the type of restorations with which the patient will have longer-term esthetic results. However, scheduling the patient for two separate appointments may be more inconvenient; people are busy and want to make the most of their time.

The second scenario is ideal for states that require direct supervision. The dentist meets the patient, reviews the medical information, and performs a brief assessment of the patient’s oral cavity. This satisfies the legal requirements for oversight (Figure 2). Essentially, the dentist gives the hygienist the go-ahead for treatment. After hygiene services are rendered, the dentist returns for a comprehensive examination. This scenario does two things: First, it helps establish trust. The dentist has an opportunity to show the patient that he or she is being placed in the hands of the hygienist with the dentist’s vote of confidence. Second, this allows the hygienist to establish a rapport with the patient and subtly promote the dentist. A patient may feel more comfortable discussing concerns with the hygienist rather than the dentist and, again, that information can be relayed to the dentist beforehand. The con to this scenario is time management. If too much time is lost when the dentist sees the patient initially, it may put the hygienist behind schedule. This can easily happen if the dentist and hygienist are not mindful of the time. In our practice, when a patient wants both a prophylaxis and a consultation with the dentist, we schedule the patient in both chairs—one following the other.

In the third scenario, if the hygienist sees the patient first, the dentist then relies on the hygienist to convey information about the patient’s concerns, personality traits, and even biographical information. With a snapshot of information gathered from the hygienist, the dentist has a better sense of how to effectively communicate with the patient. Small things, such as what name the patient wants to be called (nickname or more formal recognition), are helpful. Any recent personal problems or stress-causing events in the patient’s life may dramatically affect the way a patient receives proposed treatment. If the dentist is informed, he or she can present treatment in a manner that doesn’t overwhelm the patient.

In this scenario, it’s important to ensure that proper time is allotted, so that the dentist can complete the examination uninterrupted. “A dentist’s top daily stressors are (1) running behind schedule, (2) causing pain, and (3) heavy work load.”6 Now, imagine how a patient would feel if the dentist or other team members somehow verbally or nonverbally communicated these stressors. One example would be a hygiene patient scheduled in a way that does not allow preparation for periodontal probing, sufficient radiographs, or an intraoral examination for both caries and other potential pathology. Certainly, the interview process should be the best time to make sure the hygienist and dentist are on the same page with goals and expectations.

“The dentist-patient relationship literature provides some clear advice about patients’ expectations and perceptions when visiting a dental practice. These expectations are less related to the technical competence of the dentist, and more to do with the attitudes and communication skills. Patients want a dentist who listens to them, has a friendly, caring attitude, explains treatment options and procedures, and inspires confidence. This is consistent with research findings in the medical literature which shows . . . the most important health service factor affecting patient satisfaction is the quality of the doctor-patient relationship.”7

In any of these scenarios, it is critical that the dentist and hygienist create a sense of immediacy for the patient. “Immediacy is defined as the degree of perceived physical or psychological closeness between two people.”8 “Dental hygienists, as skilled and knowledgeable clinicians, must utilize communication skills that build patient trust and that convey their skills and knowledge.”8

The hygienist-patient relationship plays an important role in a patient’s decision to return for recurring appointments. Hygienists often spend more time with patients for preventive services than dentists do with patients for restorative treatment. Patients may be seen for preventive services two to four times per year, yet they may see the dentist only for a few minutes during examinations (Figure 3). Research has shown that along with dental hygiene treatment planning, “having a preventive structured approach in place helps individual patients to feel that their views and concerns are respected.”7 Concurrently, the same patients who reported feeling respected “talked about being compliant with preventive care recommendations, because they felt they were being treated as a person and not as a patient.”7

During a continuing-care appointment, the hygienist may “assess, diagnose, plan, implement, evaluate, and document treatment for prevention, intervention, and control of oral diseases, while practicing in collaboration with other health professionals.”9 For example, essential services—such as medical information review, blood pressure check, x-rays, probing, prophy or periodontal maintenance, fluoride application, patient education, and doctor-assisted examination—are completed during routine dental hygiene appointments. In addition, taking photographs—especially digital photos with an intraoral camera—could be of extreme importance both to the dentist and patient to document any pathological problems.

Every day, patients make decisions about a dental practice based not only on the dentist’s credentials, but also on the entire dental team. From the perspectives of the patients, the second most important part of the team is the hygienist, who will help maintain their oral care for the future. The better the relationship between the dentist and hygienist, the more likely the long-term success for the patient. Establishing written expectations, consistent communication, and effective training will ensure that the whole team is working toward the same goal.

Ronald E. Goldstein, DDS, is a clinical professor of oral rehabilitation at the Dental College of Georgia at Augusta University, in Augusta, Georgia; adjunct clinical professor of prosthodontics at Boston University Henry M. Goldman School of Dental Medicine; and adjunct professor of restorative dentistry at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, Texas. Dr. Goldstein has long been considered the “architect” of modern esthetic dentistry and wrote the first comprehensive textbook, Esthetics in Dentistry, in 1976, which is now in its third edition. His consumer book, Change Your Smile, is in its fourth edition and has subsequently been published in 12 language worldwide.

Yemia A. White, RDH, BSDH, is a registered dental hygienist in the dental practice of Goldstein, Garber, & Salama, located in Atlanta, Georgia. Ms. White is an author and researcher, as well as a member of the American Dental Hygienists’ Association and the Georgia Dental Hygienists’ Association.

References

1. Synergy. Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Merriam-Webster website. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/synergy. Accessed April 17, 2017.

2. Watt RG, Williams DM, Sheiham A. The role of the dental team in promoting health equity. Br Dent J. 2014;216(1):11-14. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2013.1234.

3. Mueller-Joseph L, Homenko DF, Wilkins EM, Wyche C. The Professional Dental Hygienist. In: Orientation to Clinical Dental Hygiene Practice. http://downloads.lww.com/wolterskluwer_vitalstream_com/sample-content/9780781763226_Wilkins/samples/97568_ch01.pdf. Accessed April 18, 2017.

4. Finkbeiner BL, Finkbeiner CA. Practice Management for the Dental Team. 8th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2016:1-12.

5. Catlett A. A comparison of dental hygienists’ salaries to state dental supervision levels. J Dent Hyg. 2014;88(6):380-385.

6. Moore R, Brødsgaard I. Dentists’ perceived stress and its relation to perceptions about anxious patients. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2001;29(1):73-80.

7. Dalonges DA, Fried JL. Creating immediacy using verbal and nonverbal methods. J Dent Hyg. 2016;90(4):221-225.

8. Sbaraini A, Carter SM, Evans RW, Blinkhorn A. Experiences of dental care: what do patients value? BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:177. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-177.

9. Standards for Clinical Dental Hygiene Practice. American Dental Hygienists’ Association (ADHA). Supplement to Access. https://www.adha.org/resources-docs/2016-Revised-Standards-for-Clinical-Dental-Hygiene-Practice.pdf. Published March 10, 2008. Revised June 2016. Accessed September 27, 2017.