Clinical suspicion of celiac disease

Early detection could be noted in dental enamel defects

By Christopher Friesen

According to a study1 published in 1989, people with celiac disease (CD) have a higher risk of developing oral cancer if they are not on a gluten-free diet. If dental professionals know more about celiac disease, and how this illness affects the entire person, including the mouth, they can help in its early detection, and possibly help their patients avoid years of suffering.

When Connecticut-based dentist Dr. Ted Malahias's wife and daughter were diagnosed with celiac disease, their pediatric gastroenterologist asked to see his daughter's teeth. Dr. Malahias knew diseases of the digestive system could manifest with symptoms in the mouth, but a link between CD and problems with teeth was new to him. Wanting to know more, he looked for research that might explain the connection.

It wasn't easy to find. The North American medical establishment is not as knowledgeable about CD as other medical establishments in the world. There were several European studies that had linked dental enamel defects to celiac disease -- that's how his daughter's doctor had known to check her teeth. CD is much better understood in Europe and other parts of the world than in the U.S.

"They're more aware of celiac disease because the connection between CD and the mouth was in the literature from 1990," Dr. Malahias said in a phone interview. "They are trained, especially in Italy, and they are more attuned to it than we are here."

----------------------------------------------------------------

See related articles

----------------------------------------------------------------

As he researched this connection more, Dr. Malahias contacted Peter Green, M.D., a researcher at Columbia University's Celiac Disease Center.

"When I called him, he already knew there was a connection between celiac disease and dental enamel, but there were no papers here and he wanted to do a paper for the U.S. literature," he said.

During that phone call, Dr. Green recruited Dr. Malahias to perform the study with the goal of linking the occurrence of dental enamel defects to CD. Dr. Malahias is a practicing dentist, not a clinical researcher or an academic, but Dr. Green needed help with conducting the study, and Malahias agreed.

"It was more of a give-back," Dr. Malahias explained. "He said 'do you want to do this study?' and I said, 'yes' because there's a need for it. The goal was to get that one statement out that there's a connection between dental enamel defects and celiac disease, and that doctors need to look for it."

To develop that conclusion, Dr. Green put Dr. Malahias in touch with celiac disease support groups. Dr. Malahias attended group functions and recruited patients and control subjects. He conducted an examination of all subjects' mouths and documented their history of aphthae. He photographed their teeth and graded the amount of enamel defects. As part of the study, Dr. Malahias asked a second dentist to examine the photographs to check his conclusions.

Dr. Malahias then passed his research along to Dr. Green, who had statisticians crunch the numbers. Other members of the research team wrote the final paper, which was published in the Journal of Gastroenterology in 2009.2

After examining the evidence, the study revealed two main findings:

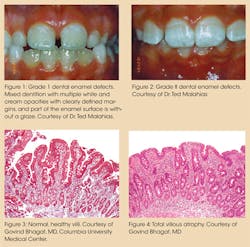

1. CD is highly associated with dental enamel defects in childhood.

2. There is an association between CD and aphthous ulcers.

The dental enamel defects appeared in childhood, the authors theorized, due to the onset of CD during enamel formation. The adults in the study did not show this same association. This may seem unusual, until the manifestation of CD is fully understood. Unfortunately, Dr. Malahias admits, his colleagues don't yet know enough about CD.

"I think they are more aware of it, but I think more has to be done to get the word out so they know the details," he said.

So what do dentists and other dental professionals need to know about celiac disease? According to Dr. Malahias, "Everything. They really don't know the details. They need to understand that it's not just an allergy, and they have to understand that the people are really ill."

What is celiac disease?

Many breakthroughs in CD research have happened during the last 20 years, but the condition is an ancient one, well documented back to the first century A.D. Aretaeus of Cappadocia, a Greek physician, described the condition and named it Koiliakos after the Greek word for abdomen, "koilia." Aretaeus understood that properly digested food was assimilated into the body somewhere in the stomach organs, and something prevented that process among his affected patients.

Eighteen hundred years later, several physicians treating children with the illness would lay the foundation for a modern understanding of the disease and its treatment.

Samuel Jones Gee, Christian Archibald Herter, and Willem Karel Dicke were some of the early pioneers in the field. At one time the condition was known as Gee-Herter disease in acknowledgement of the first two. Willem Karel Dicke is credited with pioneering the gluten-free diet as the treatment for the condition in the late 1930s and early 1940s.

Today, researchers such as Columbia's Dr. Peter Green and Dr. Alessio Fasano of the Center for Celiac Research at Mass General Hospital for Children in Boston (formerly at the University of Maryland School of Medicine) are leading the research effort. Dr. Fasano is widely regarded as an expert in the field. In 2003, his research team published the results of a landmark study3 that showed that one in 133 North Americans is affected by CD.

Dr. Fasano's study defines CD in clinical terms: "Celiac disease is an immune-mediated enteropathic condition triggered in genetically susceptible individuals by the ingestion of gluten."

As Dr. Malahias said, it's not an allergy. Rather, it is an autoimmune disorder that causes villous atrophy in the small intestine when ingested gluten produces an immune response that doesn't attack the gluten, but instead attacks the intestine.

"The gluten is deamidated by tissue transglutaminase, which allows interaction with HLA-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8 on the surface of antigen-presenting cells," Dr. Malahias said. "Gliadin is presented to gliadin-reactive CD4+T cells through a T receptor, resulting in production of cytokines that cause tissue damage."

In a healthy intestine, food is broken down by the villi. Beneath them, enterocytes work on absorbing nutrients and passing them into the bloodstream. If the body encounters a particle that requires an immune response, the enterocytes pass the immune system's cells into the intestine. Normally the enterocytes are packed tightly against one another and should remain that way.

Ingested gluten is naturally difficult to digest and, in genetically susceptible individuals, it is treated as a foreign body. The enterocytes release a chemical that loosens those tight molecular junctions between themselves, creating what Dr. Fasano refers to as a "leaky gut." Once the junctions are loosened, gluten particles can penetrate through to the layer of immune cells under the enterocytes, which triggers the autoimmune response attacking the enterocytes and causing the villous atrophy.

What are the symptoms?

Celiac disease has a variety of classical symptoms relating to problems with the gastrointestinal tract. Symptoms including diarrhea, intestinal bloating, and cramps, and these are often the first, most urgent responses to gluten ingestion. Other symptoms can include irritability and weight loss as the body's nutrient uptake system fails.

Anemia and other nutrient deficiencies are commonly related to untreated CD. Many of these symptoms mimic other conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome, lactose intolerance, or diverticulosis, which can add to the complications in diagnosing CD. In children, lack of nutrient absorption may cause delays in growth and the onset of puberty, vomiting, irritability, changes in behavior and, of course, problems with the enamel on their teeth.

According to Dr. Fasano's study, CD has a prevalence of approximately 1 in 133 people. First and second degree relatives of diagnosed individuals have a 1 in 22 chance and 1 in 39 chance respectively of also having CD.

CD can remain largely dormant for many years, but among genetically susceptible individuals it can appear at any time during their lives. Stress, pregnancy, surgery, or even infections may cause the onset of severe symptoms. CD does not discriminate and occurs on all continents, and among all racial, cultural, and age groups.

How is celiac disease diagnosed and treated?

Several blood tests have been developed to help screen for CD. Testing serological samples for anti-gliadin antibodies, the AGA test; endomysial antibodies, the EMA test; anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies, the anti-tTG test; and deamidated gliadin peptide antibodies, the DGP test, can all be used to support a diagnosis and the need for further testing. But there is only one conclusive test that physicians rely on -- conducting an intestinal biopsy and examining the damage to the villi.

Diagnosis can be difficult, and many celiac associations report that some people have sought the help of three or more doctors, and spent several years suffering before finally being diagnosed.

CD is unusual in the spectrum of autoimmune disorders because of what is known about it. Dr. Fasano's research has revealed the three main ingredients in the disease pathogenesis:

- Genetic susceptibility

- Leaky gut

- Environmental trigger (gluten)

Remove any one of these three and the condition should go away. Researchers are working on drug therapies to plug the leaky gut, but there is currently only one known treatment for CD – eliminating the environmental trigger by maintaining a strict adherence to a gluten-free diet. Any ingestion of gluten will cause illness, and as the 1989 study showed, continued ingestion increases the chance of other diseases developing.

Gluten is the combination of two proteins, glutenin and gliaden, that occur in cereal grains such as wheat, barley, and rye. Glutenin and gliaden exist independently within the whole head of the grain, but become combined into gluten when moisture is added.

When cereal grain flours are mixed with water to form dough, the combined proteins form into longer chains of stretchy molecules. Gluten provides the structure and support for trapping gasses during the rising process. Baking dries and sets the final product, but the gluten remains.

Gluten itself can be extracted from grain, and has been developed into a commercially available product that may be used as an additive in a variety of items including food, cosmetics, and dental hygiene products.

How can dental professionals respond?

Dr. Malahias says dental product companies have responded well to the need for gluten-free, and if patients or dentists aren't sure, they can check the labels on their inventory.

"Everything is labeled now," he said. "Before, you had no idea what was in a lot of polishing pastes. Now they are labeled gluten-free, preservative-free, saccharine-free. They list this. They specifically list gluten-free now."

Dr. Malahias also recommends that dentists add celiac disease to their medical history questionnaires. He says all patient questions should be treated seriously, and all concerns should be addressed with the understanding that these people are suffering from a very serious illness.

"The last thing [a patient] wants is to get sick again by something you put in their mouth," he said.

Dr. Malahias now speaks around the country, telling other dental professionals about the connection confirmed by his study. He has also started appearing at celiac education events to further get the word out. He is very interested in seeing his peers become knowledgeable on this subject because their clinical suspicions may be the first step in directing patients to physicians who can properly diagnose, or rule out, CD.

"Because we see the tissue and we see the health of the tissue, we can advise patients to go see their physicians," he said. "[Dentists] can't diagnose celiac disease, and you can't say everyone with dental enamel defects has celiac, but you should at least think about it."

Dr. Malahias's complete study and more information on celiac disease and the dental patient can be found on his office's website at http://www.bridgeworksfdc.com/page.php?t=celiac.

Christopher Friesen is a professional technical and freelance writer. His work has appeared in Connector Specifier Magazine, The Journal of Commerce, the Winnipeg Free Press, and Radio World Magazine. He and his wife publish the gluten-free recipe website, www.thebakingbeauties.com.

References

1. Holmes GK, Prior P, Lane MR, Allen RN. "Malignancy in celiac disease – effect of a gluten-free diet." Gut, 30(3):333-338; 1989.

2. Cheng J, Malahias T, Brar P, Minaya MT, Green PH. The association between celiac disease, dental enamel defects, and aphthous ulcers in a United States cohort. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010 Mar;44(3):191-4. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181ac9942.

3. Fasano A, Berti I, Gerarduzzi T, et al. Prevalence of celiac disease in at-risk and not-at-risk groups in the United States: a large multicenter study. Arch Intern Med. 2003 Feb 10;163(3):286-92.

Past RDH Issues