BY NOEL BRANDON KELSCH, RDHAP

There are several preventive techniques you can use to prevent being bitten:

- Use a bite block. Utilizing a bite block for most procedures will not only help the patient relax but will help decrease the chance of bite injury.

- If a bite block does not work with the client, a tongue depressor wrapped in 2x2s taped down is a great substitute. Foam mouth props also can be effective.

- Always have an instrument in the mouth. If there is an instrument in the mouth, the patient will not be closing all the way, and it is less likely that you will be bitten.

- Develop a protocol for bite wounds in your office when you are doing your required yearly bloodborne pathogen training.

- Have paperwork and referral sources in place before an incident occurs.

If you play with matches, you are likely to be burned. When your livelihood consists of reaching into other people's mouths, there is a chance that, at some point in your career, you will be bitten. Taking precautions to prevent a bite and being prepared in the event of a bite are the key to prevention.

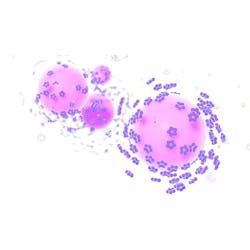

Some people may think, "I just got bitten by a kid; no big deal." It is a big deal. The act of biting can inoculate the wound with bacteria and viruses. Human saliva is a cesspool of up to 50 species of bacteria with almost 108 microbes/ml.1 This is one of the reasons why human bites are believed to have higher rates of infection than other injuries. There is a risk of transmission to the person being bitten and the person who inflicts the bite.

------------------------------------------

Other articles by Kelsch

- Donning and removing PPE: Directions are included (CDC and OSHA)

- Jenn’s vision: A true lesson in best practices

- Sealing to the limit: Sealants represent a safe and effective preventive measure across a variety of care settings

------------------------------------------

Many infectious diseases have been transmitted via human bites. Immediate treatment is a must.2 In the dental setting, the fingers and the hand are the areas most bitten. Increased rates of infection tend to occur when the area that is bitten is avascular such as joints and tendons.3 Children's bites are less likely to cause infection because of the lower rate of diseased teeth and lower incidence of gingivitis compared to adults.4

It is important to remember what the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) considers occupational exposure: Contact with blood, visibly bloody fluids, and other potentially infectious material. Exposures include percutaneous injuries, mucous membrane exposures, nonintact skin exposures, and bites. Other "potentially infectious materials" include saliva in dental procedures, any body fluid that is visibly contaminated with blood, and all body fluids in situations where it is difficult or impossible to differentiate between body fluids.

Such injuries can include piercing mucous membranes or the skin barrier through such events as needlesticks, human bites, cuts, and abrasions. OSHA states that human bites fall into the same category as any other sharps injury.5

The Organization for Safety, Asepsis and Prevention (OSAP) devotes a section of its website to "Ask OSAP." OSAP, a nonprofit organization committed to keeping both the clinician and the public safe in the dental setting, is a great resource for all offices in training and answering questions. They are very inexpensive to join.

I asked them, "What is the protocol for treating patient bites that break skin or cause bleeding in the dental setting?"

They referred me to the updated U.S. Public Health Service Guidelines for the Management of Occupational Exposures to HBV, HCV, and HIV and Recommendations for Postexposure Prophylaxis, which states:

"For human bites, the clinical evaluation must include the possibility that both the person bitten and the person who inflicted the bite were exposed to bloodborne pathogens. Transmission of HBV or HIV infection only rarely has been reported by this route."6

Additionally, the guidelines say the rare transmission of HIV via a human bite has not been reported "after an occupational exposure."7 They also noted, "Human bites may also be reportable to your local health department, and it is also recommended that you consult further with your local health department on this matter."

Lisandra Maisonet, RDH, shared her story: "We had a one-year-old in the schedule who came to us with early childhood decay on all the anterior teeth. Because of the extent of the decay, we wanted to schedule her to protect her primary molars as they were starting to show signs of early breakdown.

"The child sat on the mom's lap for the procedure, and we used a mouth prop to allow us to gain access to each of the molars. While we were working on the child, she pushed the mouth prop out of the mouth and immediately bit down on both my finger and the assistant's finger, drawing blood from the area.

"Of course, the mom was mortified that she bit us, but we explained that when working with little ones, this can occur. Usually, we are pretty quick at getting our fingers out of the mouth; however, in this occasion, the child beat us to it.

"After the visit, we had to report the incident to our employer and follow through with proper protocol."

Implementing preventive measures and knowing what to do ahead of time when a biting event occurs can make all the difference.

If you are bitten, you must take immediate action. The CDC guidelines offer a good overview of the action that is need. To view them, visit the FAQ for occupational exposure to bloodborne pathogens in the "Infection Control" section for the CDC's Division of Oral Health at cdc.gov.

Human bites are nothing to ignore. Knowing what to do for the patient and the clinician before the event occurs is the key to any good infection control program. RDH

References

1. Perron AD, Miller MD, Brady WJ. Orthopedic pitfalls in the ED: Fight bite. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20:114-7.

2. Patil PD, Panchabhai TS, Galwankar SC. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2009 Sep-Dec; 2(3): 186-190. Managing human bites.

3. Henry FP, Purcell EM, Eadie PA. The human bite injury: A clinical audit and discussion regarding the management of this alcohol fuelled phenomenon. Emerg Med J. 2007;24:455-8.

4. Griego RD, Rosen T, Orengo IF, Wolf JE. Dog, cat, and human bites: A review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:1019-29.

5.https://www.osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_id=10051&p_table=STANDARDS Accessed April 1, 2015.

6. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated U.S. Public Health Service Guidelines for the Management of Occupational Exposures to HBV, HCV, and HIV and Recommendations for Postexposure Prophylaxis. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5011a1.htm Accessed on April 1, 2015.

7. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated U.S. Public Health Service Guidelines for the Management of Occupational Exposures to HIV and Recommendations for Postexposure Prophylaxis. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5409a1.htm Accessed April 1, 2015.

8. Guidelines for the Management of Occupational Exposures to HBV, HCV, and HIV and Recommendations for Postexposure Prophylaxis. MMWR 2001;50 (No. RR-11) p. 3 Accessed April 1, 2015.

9. http://www.cdc.gov/oralhealth/infectioncontrol/faq/bloodborne_exposures.htm Accessed April 1, 2015.

NOEL BRANDON KELSCH, RDHAP, is a syndicated columnist, writer, speaker, and cartoonist. She serves on the editorial review committee for the Organization for Safety, Asepsis and Prevention newsletter and has received many national awards. Kelsch owns her dental hygiene practice that focuses on access to care for all and helps facilitate the Simi Valley Free Dental Clinic. She has devoted much of her 35 years in dentistry to educating people about the devastating effects of methamphetamines and drug use. She is a past president of the California Dental Hygienists' Association.