Maxillary injections useful for adult nonsurgical periodontal therapy

BY Laura J. Webb, RDH, MS, CDA

Comprehensive debridement of treatment areas at each appointment to thoroughly remove biofilm and calculus is the current standard of care.1 Profound pulpal and periodontal tissue anesthesia is often required to provide patient comfort during comprehensive root instrumentation (manual or power scaling) at therapeutic debridement appointments and, sometimes, during regular preventive oral maintenance.

Effective anesthesia allows the clinician to provide treatment painlessly, especially in areas of challenging pocket topography, root anatomy, and inflammation, while maximizing access for instrumentation.2,3

------------------------------------------------

Related articles

- Local anesthesia options during dental hygiene care: Answers to common questions about pain control in the hygiene operatory

- Guided anesthesia method for dental procedures may make children less agitated after sedation

- High anxiety in the dental office: It's not all in their head ... but most of it is

------------------------------------------------

The maxillary bone is less dense and more permeable than the mandible, which facilitates anesthesia by supraperiosteal injection (administered above tooth apex),4,5 especially with the use of 4% articaine.6 However, since dental hygienists are often treating large areas of the mouth during one appointment, limiting both the number of penetrations as well as the volume of anesthetic by using nerve blocks is an important consideration.

Overview of Selected Maxillary Facial Injections

The posterior superior alveolar nerve block (PSA block) - Often the maxillary molars are the first to be involved in periodontal disease.1 I find the PSA block one of the essential injections to provide for my patients, particularly when performing quadrant/sextant debridement procedures. I like it because it has a high success rate (95%) for profound and sustained anesthesia to the molar pulps and buccal periodontal and soft tissues with one injection, and because it is comfortable for the patient.

The alternative, supraperiosteal injections in this area often requires multiple needle penetrations (3 vs. 1), more volume of anesthetic (1.8 mL vs. 0.9-1.8 mL), and usually provides shorter duration of anesthesia. When combined with the anterior superior alveolar nerve block (ASA block) - infraorbital approach, described below, the entire maxillary arch on one side can be anesthetized (except palatal tissues).

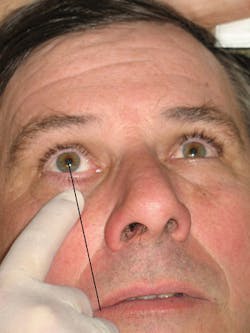

An important technique for providing the PSA block includes the insertion at the height of the mucobuccal fold distal to the zygomatic process and superior to the apex of the maxillary second molar, orienting the syringe barrel outward laterally at a 45-degree angle away from the midsagittal plane and downward at a 45-degree angle away from the occlusal plane of the maxillary teeth9 (see Figure 1).

Common errors include the failure to maintain retraction and to maintain the 45-degree angle away from the midsagittal plane. Often, clinicians begin with proper technique, but subsequently relax retraction and close the angle to the midsagittal plane (allow syringe to move toward buccal aspect of teeth). This usually results in needle movement away from the target and/or insufficient advancement due to obscuring the view of the penetration site.8

Some clinicians report that they avoid providing the PSA block due to the risk of hematoma (3%). The risk of hematoma can be minimized by using a short (to avoid overinsertion) 25-gauge needle, aspirating in two planes multiple times (to facilitate reliable aspiration) before and during the slow deposition of anesthetic.2,5,10,11

Special circumstances: Approximately 28% of the time the mesiobuccal root of the first permanent molar is not anesthetized during the PSA block.2,5 This is easily remedied by providing the middle superior alveolar nerve block (MSA block) discussed below.

If anesthesia of the posterior palate is needed, the greater palatine nerve block (GP block) (discussed below later) should be provided in addition to the PSA block. Sometimes the palatal roots of the molars are also innervated by branches of the GP nerve, and provision of the GP block may be indicated to fully anesthetize those roots.9

The prerequisites to success for anesthesia 4,5,7-9

1. Check radiographs - Consider anatomical features associated with injection (radiographically apparent landmarks, tooth apex, etc.).

2. Rehearse - Visualize the anatomy and each step of the process prior to administration. Reiterate the steps (silently) as you proceed.

3. Topical - Judicious use of topical anesthetic prior to needle penetration contributes to patient comfort.

4. Adequate retraction - Drying the tissue and gently keeping it taut (all areas except palatal) facilitates effective, painless penetration and good vision during advancement of the needle. When the tissue is allowed to collapse around the needle, it impairs our ability to see the needle movement and we may not advance the needle adequately. In some situations, the use of a 2X2 cotton gauze may help make retraction easier.

5. Fulcrum - A firm fulcrum should always be used to assist in maintaining complete control, ease of aspiration, and provision of safe and effective injections. A finger fulcrum is recommended, often on the chin, but arm-to-body fulcrum is an alternative. The palm-up type of fulcrum provides stability as the thumb of the nondominant hand can be placed on the barrel of the syringe for additional stability. When using the arm-to-body fulcrum, the arm should be positioned low and close to the body. Avoid use of patient arm/shoulder as this can be dangerous if the patient moves.

6. Needle - A 25-gauge short needle is recommended for most maxillary injections, but a 27-gauge short may be used. The 25-gauge needle is strongly recommended for posterior superior alveolar and anterior superior nerve blocks. 30-gauge needles are not recommended except with computer-controlled local anesthetic delivery systems (C-CLAD). It is important to note that hundreds of studies have been conducted indicating that patients are unable to discern between 25, 27, and 30-gauge needles.

7. Aspiration - To avoid intravascular injection, multiple aspirations are recommended in two planes (rotate barrel 1/4 turn, reaspirate, rotate back, and reaspirate) before deposition. Periodically aspirate throughout the injection. This technique helps to ensure that the bevel is not against the vessel wall resulting in a false negative aspiration. Aspiration success is facilitated by use of the 25-gauge needle.

8. Slow advancement and deposition - It is recommended to deposit a few drops and wait a few seconds before advancing the needle to the target. Higher accuracy (less needle deflection) is associated with use of the 25-gauge needle. Rates of slow deposition are discussed below under specific injections, but generally, after negative aspiration, the safe and comfortable rate of deposition is 1.8 mL over two minutes.

9. Good patient communication - Part of pain management includes alleviating patients' fears and gaining trust before and during the injection procedure. Allow patients an avenue to communicate with you during the injection (for example, raising hand on opposite side of clinician) and reassure them throughout procedure.

The middle superior alveolar nerve block (MSA block) - The MSA block is of limited clinical value because the MSA nerve is present in only approximately 28% of the patient population. For those patients, the MSA block may be required in addition to the PSA block or ASA block to ensure anesthesia for premolars, the mesiobuccal root of the maxillary first molar, and the associated periodontal tissues.4,5,9

Generally, it is a simple injection. Insertion is at the height of the mucobuccal fold above the maxillary second premolar, targeting the bone well above the tooth apex (check radiographs!). If deposition is too low, only the second premolar will be anesthetized. The most common causes of inadequate anesthesia include deposition too far from the target and inadequate volumes of anesthetic.

The anterior superior alveolar nerve block (ASA block): infraorbital (IO) approach - I prefer this ASA block approach (sometimes referred to as the infraorbital nerve block) for debridement procedures during nonsurgical periodontal therapy, because it provides profound anesthesia to a wide area, often the central incisor through the mesiobuccal root of the first permanent molar (structures innervated by ASA and MSA nerves). Multiple penetrations and excess anesthetic (0.9-1.2 mL versus 3.0 mL) may be avoided with this approach.5,9 The ASA block-IO approach is complementary to the PSA block when hemimaxillary debridement is desired during one appointment.

The insertion site is over the first premolar with deposition in the area of the IO foramen (see Figure 2a). What is important to success in administering this ASA block is to properly locate the IO foramen by palpating the infraorbital notch with the index finger (when treatment is on the same side as the clinician) or thumb (when treatment is on the opposite side of the clinician) of the nondominant hand and sliding the finger down to feel the depression of the infraorbital foramen (see Figure 2b).

Figure 2a: Anatomical features for infraorbital foramen

Following basic guidelines for injections listed above, advance slowly, approximately 16 mm, and gently contact bone. It is important to maintain parallelism with the long axis of the tooth to avoid premature contact with bone. During deposition, feel for the anesthetic under the finger (filling the depression). By the end of the injection, the depression should not be felt. After the injection, maintain the gentle finger pressure over the foramen for about two minutes, and wait an additional three to five minutes before proceeding with treatment.

Although the literature supports that following proper protocols results in the safe and effective administration of this ASA block,2,5 it is often underutilized. In my experience, students have found this injection to be simple and have performed it safely.

The most common technique errors include not maintaining gentle external pressure just below the infraorbital notch during and after the injection and failure to contact bone (upper rim of the infraorbital foramen). These errors may be corrected by taking time to carefully identify/palpate the anatomy and align the needle properly (Figure 2b), applying adequate retraction/pressure with the nondominant hand (Figure 2c), and allowing the patient to provide the pressure postinjection. The most common causes for failure of anesthesia are low deposition, inadequate volume of anesthetic, and inadequate postinjection pressure. Since the ASA block does not provide anesthesia to the palate, palatal injections may be needed.

ASA (supraperiosteal approach) - This approach is useful for anesthesia of the central, lateral, and canine on one side and is used most often in conjunction with the MSA block.

It differs from the ASA block-infraorbital approach in that:

• Only the ASA nerve is anesthetized.

• Only the central through the canine teeth and associated facial periodontium are anesthetized.

• The insertion site is the height of the mucobuccal fold above the canine.

• Diffusion of anesthetic through bone is required (ASA block-IO approach anesthetizes the nerves directly at the infraorbital foramen).

Failure of anesthesia is most often related to deposition being too far from the target and inadequate volumes of anesthetic.

Please note that, since the incisors can receive sensory innervation from the ASA nerve on the opposite side (overlapping fibers), sometimes there is a need to provide a supraperiosteal injection over the contralateral central incisor when providing ASA injections.4,9

Overview of Selected Maxillary Palatal Injections

Patients often require palatal anesthesia during nonsurgical periodontal procedures, but sometimes hygienists are reluctant to provide palatal injections. They fear that the injections will be uncomfortable for the patient. The provision of palatal injections should be perfected, not feared. Key to providing atraumatic palatal injections is knowing that you can!2,5

Greater palatine (anterior palatine) nerve block (GP block) - The GP block anesthetizes the greater palatine nerve and is useful for anesthesia of the posterior palatal tissues on the side of treatment. For nonsurgical periodontal debridement procedures, it is typically provided immediately following facial injections in the posterior region of one quadrant/sextant.

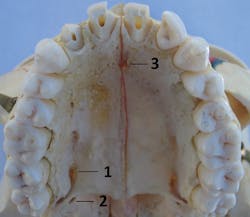

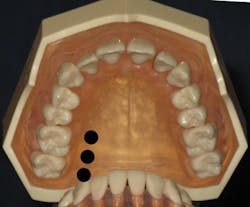

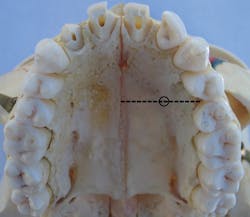

Usually located distal to the maxillary second molar, the greater palatine foramen (see Figure 3) may be found anterior or posterior to that position.5 The clinician finds the location of the foramen by using a cotton-tipped applicator to firmly palpate from the first molar region at the junction of the alveolar process and the hard palate toward the third molar. A small depression will be felt usually at some point between the distal of the first molar and mesial to the third molar (see Figure 4). Pressure anesthesia is placed at the area of the foramen and the insertion site is just anterior (see Figure 5).2,4,5,9

Figure 3: Anatomical features: 1. Greater palatine foramen, 2. Lesser palatine foramen, 3. Incisive foramen

A pre-puncture technique (see Figure 5) prior to penetration involves applying controlled pressure to the bevel to gently bow the needle on top of the site of insertion and expressing a few drops of anesthetic on the surface of the tissue.5 The needle is then straightened followed by penetration at about 90 degrees (see Figure 6) to the bone. Drops of anesthetic are advanced ahead of the needle, which aids in a more comfortable injection. The depth of penetration is approximately 5 mm, and after negative aspiration in two planes, the 0.45 mL-0.6 mL of anesthetic should be deposited slowly over 30 to 45 seconds.5 Pressure should be maintained with the cotton-tipped applicator over the foramen until deposition is completed.

Special circumstances - Inadequate anesthesia near the maxillary first premolar may result due to overlapping fibers from the nasopalatine nerve. The soft palate may be anesthetized due to the close proximity of the lesser palatine nerve (foramen) to the greater palatine foramen (see Figure 3), resulting in minor discomfort for some patients.

Figure 5: Pre-puncture technique for GP block

With a 95% success rate, failure of anesthesia is usually a result of deposition too shallow or too far anterior from the target.

The nasopalatine nerve block (NP block) - The NP nerve block is perhaps the most avoided of all palatal injections. Areas of anesthesia include the bilateral palatal tissues of the centrals, laterals, and canines.

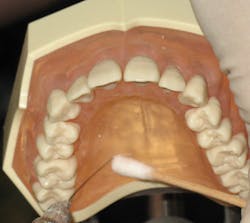

Method No. 1: Traditionally, the NP block has been provided as one injection employing the general palatal injection techniques described previously. Pressure anesthesia is placed directly on or from the contralateral side of the incisive papilla.4,5 Insertion is just next to the incisive papilla (see Figures 7, 8c) at a 45-degree angle. Avoid insertion of the needle directly into the incisive papilla, which is very painful for the patient. The target is the incisive foramen (Figure 3) just beneath the incisive papilla. Advance 3 to 6 mm (until contact with bone); withdraw 1 mm; aspirate in two planes; and if negative, deposit no more than 0.45 mL (1/4 cartridge) very slowly over 20 to 40 seconds while keeping pressure on the incisive papilla with the cotton-tipped applicator throughout deposition.4,5,9

Method No. 2: An option to the traditional approach to the NP block that many hygienists employ is the technique where two penetrations prior to the palatal penetration are performed. This three-step technique takes longer, but it is well worth the time spent (see Figures 8a-c)

The first injection is an infiltration into the labial frenum, anesthetizing the facial soft tissues in the area. The second injection is into the already anesthetized interdental papilla between the central incisors (look for blanching on the palate). Finally, the third is directed into the palate at the traditional insertion site, next to the incisive papilla. Because the palatal tissue should be anesthetized by the second injection, topical anesthetic, pressure anesthesia, and very slow advancement techniques are usually not required for the third injection.2,5,9

Failures of anesthesia for the NP block are usually related to inadequate depth or inadequate volume of anesthetic. When anesthesia is limited to one side, it is usually a result of not advancing to the opposite side of the incisive canal. Inadequate anesthesia to the canine may be due to overlapping fibers from the greater palatine nerve.

Anterior middle superior alveolar nerve block (AMSA block) - This simple and safe injection has become increasingly popular with dental hygienists over the last decade because it provides anesthesia to the pulps, periodontium, and gingival tissues for areas usually covered by the ASA, MSA, GP, and NP nerve blocks without anesthesia to the soft tissues of the upper lip and face. Patients appreciate the lack of numbness of the lip and face.

The ability to anesthetize an entire quadrant with only the PSA block and AMSA block combination results in reduction of the total number of injections (two vs. four to five) and total volume of anesthetic (1.6 to 2.0 cartridges vs. 2.0 to 3.0 cartridges).

A 27-gauge short is most commonly recommended but a 30-gauge extra-short9 has also been suggested for use for this injection due to the short advancement to the palatal bone at the injection site. Some studies suggest that it is more easily performed by computer-controlled local anesthetic delivery (C-CLAD) system which precisely regulates pressure and volume ratio of solution delivered.12 However, many clinicians feel that this injection can be successful with use of a standard aspirating dental syringe.5

The insertion site is located approximately halfway on an imaginary line connecting the palatal suture and the free gingival margin between the premolars (see Figure 9). General techniques for palatal injections, as described previously, are used. But insertion, advancement, and deposition should be much slower. The needle is angled at 45-degrees and advanced very slowly, 1-2 mm every four to six seconds until resistance is met (usually 3-5 mm). After negative aspiration, the deposition consists of 1/2 to one cartridge over a minimum of three minutes (0.5 mL/minute).4,9 Careful attention to pre-puncture and slower advancement techniques should be appreciated.

Figure 8a: Three-step penetration approach to the NP block

Special considerations: Additional infiltration may be needed for centrals and laterals due to overlapping fibers of the contralateral ASA nerve.4,9 The depth and duration of pulpal anesthesia has been debated, and some studies suggest that it may not be adequate for nonsurgical periodontal procedures even with the use of C-CLAD.12

Failure of anesthesia may be due to inadequate depth or volume of anesthetic.

Decision-making

• Administer anesthetic only in areas that will actually be treated comprehensively.

• Choose types of injections and anesthetic agents that are appropriate for the duration of the appointment and extent of instrumentation required.

• Determine the need for hemostasis. Although not usually a problem when using anesthetics with vasoconstrictor, when providing block anesthesia, additional papillary infiltration may be needed in areas of heavy bleeding.

Provision of local anesthesia is an important service that many of us are able to legally provide for our patients. Personal preferences and experiences play an important role in determining which injections we are comfortable with providing.

The general discussions of the injections above are intended to serve as an overview regarding popular injections for nonsurgical periodontal procedures and to stimulate interest in further exploration of the detailed protocols, strengths, and challenges associated with them. It is important to continue to review the literature for product and protocol updates, consider what is most safe and effective, and assess our personal techniques so that we can provide the very best care for our patients. RDH

The prerequisites to success for Palatal Injections 2,4,5,8

1. Adequate topical application (two minutes) for keratinized hard palatal tissue

2. Pressure anesthesia with cotton-tipped applicator utilizes the gate-control theory of pain by producing a dull ache that blocks the pain impulses produced during needle penetration

3. Pre-puncture technique includes expression of drops of anesthetic prior to penetration

4. Maintaining control of 27-gauge short needle with stable fulcrum orienting the bevel toward tissue/bone

5. Slow advancement and deposition of small volumes ahead of needle

6. Negative aspiration in two planes

7. Slow deposition

LAURA J. WEBB, RDH, MS, CDA, is an experienced clinician, educator, and speaker who founded LJW Education Services, www.ljweduserv.com. She provides educational methodology courses and accreditation consulting services for allied dental education programs and CE courses for clinicians. Laura frequently speaks on the topics of local anesthesia and nonsurgical periodontal instrumentation. She was the recipient of the 2012 ADHA Alfred C. Fones Award.

References

Beemsterboer P. 2014 Periodontology for the Dental Hygienist, 4th ed; Elsevier.

Darby L, Walsh M. 2010 Dental Hygiene Theory and Practice , 3rd ed; Saunders.

Wilkins E. 2013 Clinical Practice of the Dental Hygienist, 11th ed; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Logothetis D. 2012 Local Anesthesia for the Dental Hygienist; Elsevier.

Malamed S. 2013 Handbook of Local Anesthesia 6th ed; Elsevier.

Costa CG, Toramano IP, Rocha RG, Francischone CE, Totamano N. Onset and duration periods of articaine and lidocaine on maxillary infiltration. J. Prosdent. Oct 2005 94(4): 381.

Webb L. Local confidence: regain that confident feeling about anesthesia. RDH. Dec 2009; (29)12:36-37.

Webb L. Pain control: the options - tips for providing less popular injections. RDH. Apr 2010; 30 (4): 58-65.

Bassett, DiMarco, Naughton. 2010 Local Anesthesia for Dental Professionals. Pearson.

Blanton, Jeske. Avoiding complications in local anesthesia induction - Anatomical considerations. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003. 134 (7): 888-893.

Freuen ND, Feil BA, Norton NS. The clinical anatomy of complications observed in a posterior superior alveolar nerve block. The FASEB Journal 2007; 21:776-94.

Logothetis D, Fehrenbach M. Local anesthesia options during dental hygiene care. RDH June 2014; 34(6).