Background information

The general population census of the town selected was 21,262.1 As reported by the director of the preschool, 5% of enrolled students receive Medicaid assistance. The median household income for a family is $47,500 annually.2 There are 5.6% of families, and 8.7% of the population living below the poverty line.2 We found seven dental offices located in and around the area, which gives a dentist to population ratio of 1:3,037.

The community has well water and some areas of groundwater; however, the levels of fluoride range 0.23-0.38ppm.3 According to the American Dental Association, as published by Wilkins (2012), this reveals an inadequate level of fluoride for children in the age demographic of 3-5 years. Fluoride supplements were recommended to parents on recommended guidelines.4

Feedback from parents

A survey was sent home to the parents by each child’s teacher; 69% of the surveys were returned. All but two families noted their child had seen a dentist by age 4. When asked how frequently their child sees the dentist, half noted for emergency visits only and the other half took their child every six months.

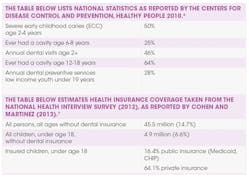

These results fit in with national statistics as reported by Chu (2006), who states “about half of all children age 2-17 usually have a dental checkup at least once a year. Almost half of all children (32 million) did not usually have such checkups.”5 Key responses from parents on why they did not seek preventive dental care for their child included:

- No insurance. Once again, as reported by Chu (2006), this response lines up with national statistics in the United States. “Inability to afford care was cited by more than half of the children who experienced barriers to dental care (55.7 percent) as the main reason needed dental care was not received.”5

- Planning on going to the dentist soon.

- Pediatrician said not to take my child until three and a half years of age.

- Hard to find a dentist where we live.

- My child has no cavities; no need to see the dentist.

- Bad experience with first dental visit; it was a disaster.

- Afraid of dentist (we were not sure if this is parental fear or child’s fear).

- Most parents (99%) reported brushing their child’s teeth at least once a day. There were two children being sent to bed with a sippy cup or bottle of milk and/or juice.

Educational, but fun

Our overall goal was to make oral home care fun and rewarding for young children while encouraging parents to play an active role in their children’s home oral health. By developing positive oral habits earlier in life, our hope is to reduce the number of dental emergencies experienced by this population and to reduce dental anxiety in young children. This will foster a lifelong commitment to oral health.

Teaching methods for the children included puppet shows as well as tell-show-do interactive activity stations on brushing, flossing, healthy diet, and caries. An information desk to address parental questions was provided. Parents were advised to provide fluoride supplementation for their children based on the water fluoridation deficiency of the area. Education stressing frequent dental visits starting no later than one year of age was provided, as well as prevention for baby bottle tooth decay.

------------------------------------------------------------

Other articles by Dowst-Mayo

- ObamaCare and dentistry: The Affordable Care Act stirred up plenty of controversy, but dental professionals should stay focused on how it affects their livelihood

- Expectations of wages: Know what you are worth and believe in what you are worth

- Breakin' time down! The anatomy of dental hygiene appointments often lead to wonderment about where the time went

------------------------------------------------------------

Since many families in this rural area are at or below the poverty line, having adequate oral hygiene supplies can be a financial barrier. Advice for proper oral hygiene aids and maintenance was provided along with a free goodie bag containing a toothbrush (provided by Colgate), toothpaste (provided by Colgate), floss picks, and a reward chart for daily brushing with stickers.

Dental professionals with a working awareness of the above national statistics can apply that knowledge to the needs of their own communities. In rural areas such as the community health project described above, the parents tend to be very caring and attentive to their children’s needs. But with a lower education level, many times they were just not informed of proper preventive oral health care. Research shows the children in households where neither parent attended college were less likely to have an annual dental checkup (33.2%) vs. households where one parent attended or graduated college (60.9%) (Chu, 2012).5

We should not allow our busy lives in private practice to blind us as to the needs of the general population in which we serve. Health-care professionals generally practice with altruistic motives, and our personal goal is to carry these motives throughout our careers. If more dental hygienists reached outside their individual practices to serve those with limited access to oral health, imagine the lives that could be changed. RDH

Lisa Dowst-Mayo, RDH, BSDH, graduated magna cum laude with a degree in dental hygiene sciences from Baylor College of Dentistry in 2002. She is currently pursuing a master’s in health administration from Ohio University. She is a full-time professor at Concorde Career College in the dental hygiene department where she teaches clinical sciences, board review, special needs, and pharmacology. She is a published author and national speaker and can be contacted through her website at www.lisamayordh.com.

Nicole Backes, RDA, RDH, graduated from Concorde Career College graduated in May 2015 with an associate’s degree in applied science in dental hygiene. She participated in many campus activities and was part of the leadership enrichment program. She worked as a dental assistant in California and Arizona for five years prior to entering dental hygiene school. She currently resides in Canyon Lake with her loving husband and rambunctious four-year-old son, Hayden.

References

- United States Census Bureau. (2013). State and country quick facts: Canyon Lake, CDP, Texas. Retrieved from https://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/48/4812580.html

- United States Department of Commerce, United States Census Bureau. (2013). Selected economic characteristics. Retrieved from https://factfiner.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk

- Canyon Lake water service company. (2015). Make every drop count. Retrieved from http://www.clwsc.com/water-quality/waterquality.php?mn=7&sm=7-1

- Wilkins E. (2012). Clinical practice of the dental hygienist. (11th ed.) Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA.

- Chu J. (2006, January). Medical expenditure panel survey, AHRQ. Retrieved on January 3, 2015 from http://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_files/publications/st113/stat113.shtml

- Centers for Disease Control (n.d.). Healthy People 2010: Progress review focus area 21 – oral health presentation. Retrieved on January 3,2015 at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ppt/hp2010/focus_areas/fa21_2_ppt/fa21_oral2_ppt.htm

- Cohen R, Martinez M. (2013, March). Health insurance coverage: Early release of estimates from the National Health Interview Survey 2012. Division of Health Interview Statistics, National Center for Health Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/releases.htm