Mouthful of Slugs

by Lynne H. Slim, RDH, BSDH, MSDH

When I put on my thinking cap and reflect on how we treat periodontal infections, I truly believe we're functioning in a knowledge vacuum. We're groping around, trying to determine what's scientifically and clinically relevant, and sometimes we use outdated therapies that don't "cut the mustard." When I interact with clinicians who are stuck in old school ways of thinking about infection, I realize it's not always their fault. Old theories like "dental flossing on its own prevents proximal caries" are based on erroneous assumptions, and it takes time and education to correct these fallacies.

In this two-part column, I'll explore chronic wounds and biofilm infections. My goal is that you, the masterful and cunning clinician, will come away with a new appreciation for these extremely complex and debilitating ailments. I want you to adopt a novel way of thinking about and presenting this relatively new science to your patients, and I'd be thrilled if we could get patients to understand what is meant by a biofilm infection. Whether I'm successful or not in this effort, please write me by e-mail or preferably by a letter to the editor to RDH magazine. We love to hear from you, and your thoughts are invaluable and much appreciated!

At a recent seminar on employment law compliance and human resources, hosted by Bent Ericksen and Associates, I was reminded that when we communicate, only 7 percent of our message is communicated through our words, and 38 percent is communicated through our vocal tone. A whopping 55 percent is communicated through facial expression or other visual cues. Unless you've got a phase contrast microscope in your operatory, it's tough to come up with a visual cue to engage patients in the learning process when you're talking about periodontal pathogens.

It's been a long time since dental plaque was presented to patients in a unique and gripping manner, and I credit Dr. Robert F. "Bob" Barkley for getting patients excited about the subject. Dr. Barkley was a pioneer of preventive dentistry in the late 1960s. Not only did he recommend removing a plaque sample from a patient's mouth and serving it on a cracker, he is credited with saying, "Brushing is a hoax, so throw the brush away and only floss the teeth you want to keep."1 We still hear this quote today, and I've worked for many a dentist-employer who reminds patients that interdental cleansing is essential for good periodontal health.

A cue is a signal or reminder of something. The concept of cueing is important to visual communication because it provides a framework that is filed in our memory banks. The phase contrast microscope provides a good view of some of the creepy crawlies that live in a periodontal pocket. Dancing and twirling microorganisms motivate patients, but are we presenting a true representation of the 21st century? I think not, and I know I've said this before!

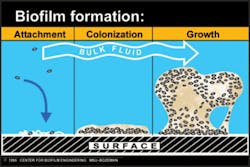

Microorganisms in periodontal pockets and supragingival areas live in a biofilm. Biofilm communities are difficult to explain to patients, even when we tell them that the "bugs" live in a slimy substance that sticks to the tooth. We can show them a nice laminated photo of a biofilm and compare it to a condominium tower, but I'd like to go beyond that metaphor and make it even more explicit. Before I do, I must warn the reader to be ready for a bit of a shock.

I'm learning more about biofilm by reading about biofilm-based wound management. I discovered the topic by accident when I clicked on the Center for Biofilm Engineering Web site at http://www.erc.montana.edu. On the home page was an article about a wound care center involved in a federal government grant to heal chronic wounds based on the theory that they are colonized by bacterial biofilm. Dr. Randy Wolcott, one of the key investigators who works at a wound care center in Texas, said, "We used to have literally 10 to 15 patients a month in for amputations. Now we've gone months without any. It's huge." Because I'm such a nerd, I now read a lot about biofilm-based wound management, and my search for addtional material landed me at a Web site that posted a chapter from a textbook on biofilms and wound management written by Dr. Wolcott.

Collaboration with professionals outside our discipline can lead to new insights and challenge our assumptions. After reading about the connection between chronic wounds and biofilm, I now have a new appreciation for the complexity of mature biofilm in different types of wound beds and in nature. Unlike planktonic bacteria that we see under the phase contrast microscope, biofilm is organized in a way that allows the bacteria to survive assaults like biocides (antimicrobials), antibiotics, immune system responses, and other environmental stresses.

A mature biofilm is about 60 to 200 microns thick with pillar-like attachments and enlarged tops called "mushrooms." According to Dr. Wolcott, individual biofilms are true multicellular organisms.2 The layers of bacteria are encased in a gooey, slimy substance similar to the slime of a garden slug. When I started thinking about the slugs in my gardens, I decided I needed to experience the slime for myself. Off I went on a slug hunt on a rainy day because I read that they tend to suck up moisture like a sponge on damp days.

It didn't take me long to find a good specimen, a tan-colored one on the back of a wide leaf. I donned rubber gloves, removed it from the leaf, and took my gloves off so I could experience the slimy substance firsthand. It was a lot like glue and rubber cement (I have read this to be true) and discovered that it became slimier when I tried to rinse it off. I had to roll it between my hands or with a washcloth (just as we debride pockets to disorganize the slime that encases bacteria).

My four dogs were fascinated too, and I had to keep their noses (dachshunds with keen and long noses!) away from the sticky substance, which was a challenge. They were more interested in the slug than in the slime, but when challenged by my ferocious dogs (just kidding), the slugs seemed to secrete more slime and hunk the assault. Slug slime, like oral biofilm slime, is used for locomotion, self-defense, and moisture control. Slugs use slime trails to find each other and to mate, and I wouldn't be surprised if oral biofilm slime has more functions that have yet to be discovered.

Now that I've piqued your curiosity, you'll have to wait until next month when I continue to unlock the secrets of slugs and biofilm. Happy slug trails to you until we meet again. (Nerdy and corny, that's me.)

About the Author

Lynne H. Slim, RDH, BSDH, MSDH, is a practicing hygienist/periodontal therapist who has more than 20 years' experience in both clinical and educational settings. She is also president of Perio C Dent Inc. (Perio-Centered Dentistry), a practice-management consulting firm that specializes in creating outstanding dental hygiene teams. Lynne is a member of the Speaking and Consulting Network (SCN) that was founded by Linda Miles, and has won two first-place journalism awards from ADHA. Lynne is also owner/moderator of a periodontal therapist yahoo group: http://yahoogroups.com/group/periotherapist. She can be contacted at [email protected].

References

1.http://www.dentalcompare.com/featurearticle.asp?articleid=272

2. http://woundcarecenter.net