Hygienists are some of the only preventive specialists who are in the position to discuss patients’ oral health in conjunction with other overarching health issues. In addition to oral and systemic health, gut health is one of the most important topics to broach with patients.

Gut health is defined by the balance of bacteria and combination of many organs that work together to adequately and efficiently perform functions of the gastrointestinal tract, such as eating and digesting food comfortably.1 An area that was once underresearched, new insight into gut health now presents a wealth of information that supports a link between a healthy or unhealthy gut and a person’s oral health.

As hygienists know, periodontal disease is a multifactorial disease that not only develops from bacteria present in the mouth, but also from the response of the host. Current literature shows that the bacteria alone is not solely responsible for the many types of periodontal disease and “it is becoming increasingly apparent that it is the host inflammatory response to the subgingival bacteria that is responsible for the tissue damage and, most likely, progression of the disease.”2 One of the contributing factors to periodontal disease lies in the health of and bacteria in the gut.

What the gut does

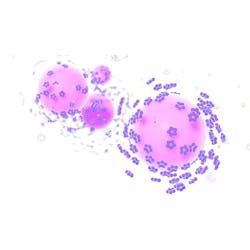

The gastrointestinal system is not only responsible for consumption and digestion of food; it also plays a central role in immune system homeostasis, constantly interacting with bacteria, viruses, fungi, protozoa, and helminths, as well as other toxic substances or useful flora.3 More than 70% of our immune response comes from the cells within the gut. A single drop of fluid from your colon contains over a billion bacteria.

Your gut bacteria reflects everything about you, including “your parents’ health, how and where you were born, what you’ve eaten (including whether your first sips were breast milk or formula), where you’ve lived, your occupation, personal hygiene, past infections, exposure to chemicals and toxins, medications, hormone levels, and even your emotions (stress can have a profound effect on the microbiome).”4

Gut bacteria play an essential role in keeping our bodies healthy. Some of the roles our gut bacteria have are:4

- Converting sugars to short-chain fatty acids (SFCAs) for energy

- Crowding out pathogens

- Digesting food and absorbing nutrients such as calcium and iron

- Keeping pH balanced

- Maintaining the integrity of the gut lining

- Metabolizing drugs

- Modulating genes

- Neutralizing cancer-causing compounds

- Producing digestive enzymes

- Synthesizing hormones and vitamins

- Training the immune system to distinguish friend from foe

When trying to determine what factors are contributing to a patient’s disease, the health of the gut microbiome must be evaluated due to its many functions and contributions to the body.

Promoting a healthy gut

Though our culture craves wellness, health protocols usually revolve around fitness and diet and rarely discuss how to increase the health of the millions of microscopic friends in our gut.

When looking to promote a healthy gut (for yourself or your patients) there are many things that can have a positive effect, including:

Fiber. It creates short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and lowers the inflammatory reaction. Pre- and probiotics help feed the microbiome. Eat a variety of fresh vegetables and fruit.

Exercise. Weightlifting increases SCFAs for the next 18 hours and reduces inflammatory responses.

Intermittent fasting. This has been clinically proven to reduce inflammation.5

Reducing stress. When stressed, long-term healing is reduced, the mucus layer in your gut thins out, cortisol is elevated, sleep quality and quantity decreases, gut bacteria decrease in diversity, and glucocorticoids destroy cells in the brain.

Getting adequate sleep. Our bodies heal when we sleep. Digestive issues are common in people with regularly disrupted sleep.

Gut health and periodontal disease

We already know about the proven relationship between periodontal disease and diabetes, obesity, and Alzheimer’s and cardiovascular diseases, but the gut is less discussed. However, an unhealthy gut results in many diseases and disorders.

Inflammation is the key player in most disease processes, including periodontal diseases and the diseases of the gut (e.g., Crohn’s, celiac, IBS, etc.). When the body is overridden with inflammation, each system functions less effectively.

When bacteria invades the sulcus, it travels through the epithelial lining of the pocket and is then circulated through the body.6 It triggers an immune response, which prompts the production of proinflammatory cytokines in the pocket, which then can also enter into systemic circulation, causing systemic inflammation.6

The bacteria in the mouth (whether by traveling from the mouth through the digestive tract or from seeping into systemic circulation) then arrives in the gut where it causes additional inflammation. The dysbiosis of the gut microbiota is one of the first reactions that can happen after periodontal disease.7 Once these pathogens become predominant, they wreak havoc in the gut microbiome, causing inflammation and organ dysfunction.

Oral pathogens such as P. gingivalis have been proven to show inflammatory changes in adipose tissue and liver, decrease gut barrier function, and significantly alter microbial communities in the gut, showing higher numbers of pathogenic bacteria and less diversity in the microbiome.7,8

By affecting the gut, oral pathogens thus affect all the functions the gut carries out. When the gut is unhealthy, it’s unable to perform these operations efficiently. The immune system is compromised and is unable to defend the body against pathogenic microbes, including those in the mouth.

The oral environment is likewise affected by the dysbiosis of the gut microbiome. The overgrowth of harmful bacteria can cause local and systemic inflammation, contributing to oral health issues. The mouth will often be the first representation of disease, which can be true of poor gut health as well. For example, a swollen tongue can be a sign of vitamin deficiency or immune imbalance. Overgrowths of certain bacteria or fungi can present as lesions or candida infections. Red and inflamed gums that are not plaque-induced can be indicative of poor mineral absorption. All of these oral dysfunctions point back to gut health.

Widening our recommendations

Though brushing and flossing are a big part of the picture, they’re not the whole picture, and periodontal diseases happen as a result of many things. It’s our job as clinicians to give the whole picture to each individual in order to provide exemplary, comprehensive care.

Many periodontal diseases can be easily remedied by increases in diligent home care and enacting strict protocols, but for the disease that is not reduced or eliminated, other factors must be considered and discussed.

When determining where a patient’s disease stems from, systemic health needs to be addressed, but specifically, gut health. This includes how the gut contributes to disease, how the oral pathogens can affect the gut, and how the patient can improve their gut microbiome, and therefore, their oral health.

The research of and connection between these two systems is growing daily, providing us with more evidence and information to further propel our patients toward systemic and oral health.

Editor's note: This article appeared in the July 2021 print edition of RDH magazine.

REFERENCES

- What is ‘gut health’ and why is it important? UC Davis Health. July 22, 2019. Accessed January 20, 2021. https://health.ucdavis.edu/health-news/newsroom/what-is-gut-health-and-why-is-it-important/2019/07

- Bartold PM, Van Dyke TE. (2017, October). Host modulation: Controlling the inflammation to control the infection. Periodontol 2000. 2017;75(1):317-329. Accessed January 20, 2021. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28758299/

- Vighi G, Marcucci F, Sensi L, et al. Allergy and the gastrointestinal system. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;153(Suppl 1):3-6. Accessed January 20, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2515351/

- Chutkan R. The Microbiome Solution: A Radical New Way to Heal Your Body from the Inside Out. 2015; Penguin Random House LLC. Accessed December 7, 2020. https://www.amazon.com/Microbiome-Solution-Radical-Heal-Inside-ebook/dp/B00RW1ZUCS/ref=sr_1_1?crid=11ZKYU1RPOWT3&dchild=1&keywords=the+microbiome+solution&qid=1607392460&sprefix=the+microbiome%2Caps%2C252&sr=8-1

- Faris ME, Kacimi S, Al-Kurd, RA, et al. Intermittent fasting during Ramadan attenuates proinflammatory cytokines and immune cells in healthy subjects. Nutr Res. 2012;32(12):947-955. Accessed January 20, 2021. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0271531712001820

- Preshaw PM, Taylor JJ. How has research into cytokine interactions and their role in driving immune responses impacted our understanding of periodontitis? J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38(Suppl 11):60-84. Accessed January 20, 2021. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21323705/

- Nakajima M, Arimatsu K, Kato T, et al. Oral administration of P. gingivalis induces dysbiosis of gut microbiota and impaired barrier function leading to dissemination of enterobacteria to the liver. PloS One. 2015;10(7):e0134234. Accessed January 20, 2021. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0134234

- Arimatsu K, Yamada H, Miyazawa H, et al. Oral pathobiont induces systemic inflammation and metabolic changes associated with alteration of gut microbiota. Scientific Reports Open Access. May 6, 2014. Accessed January 20, 2021. https://www.nature.com/articles/srep04828