The ballad of time, money, and instrument sharpening

Sharpening in the trenches: Survey results

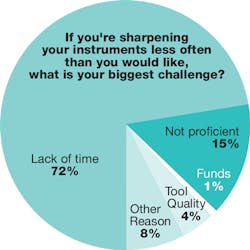

Instrument sharpening is rarely part of discussions about the business model of dental hygiene. This isn’t surprising given that sharpening is often literally left out of the hygienist’s day, whether he or she likes it or not. Our recent survey on sharpening revealed that of hygienists who say they aren’t sharpening as much as they’d like, 73% cite a lack of time as the main issue.

From our survey, it also became clear that some hygienists’ employers (both individual dentist-owners and DSOs) don’t value sharpening. They don’t provide reasonable time to accomplish it, expecting hygienists to do it after hours—that is, unpaid. Some employers even downright discourage it. One respondent said, “The doctor gets upset when we sharpen and thinks we will ruin the instruments.” There were many other comments such as this one.

Why is something as central to the practice of dental hygiene as a sharp scaler so neglected in some practices’ models of productivity and everyday activities? Why should hygienists feel confident in including sharpening as an important part of their work, both as clinicians and as generators of revenue? In this installment, we’ll explore these questions and hear what experts have to say about them.

The money

Let’s be cynics for a moment. We all know that not every dental professional has the patient’s best interests at heart. We’ll explore the clinical consequences of dull instruments in an upcoming article, but what about consequences that are spelled out in dollars? Sometimes even dire clinical consequences are not enough to push a practice owner to prioritize patient care, but such a person or entity will pay attention when the practice loses money. So, it’s worth asking: Can dull instruments actually hurt a practice’s bottom line?

The answer is unequivocally yes. Dianne Watterson, MBA, RDH, told us that “when hygienists work with dull instruments, they cause more discomfort to the patients, plus they do not remove the calculus thoroughly. This often results in continuing perio problems that necessitate referral to the periodontist’s office.” Bam—right there you have lost revenue in the form of a referral.

She continued, “Patients get disgusted and move on to another office. So the bottom line is that dull instruments can result in loss of patients because of poor and uncomfortable care. The problem of patient attrition is a big [one] in some offices, meaning they lose more people per month through the back door than the number of new patients coming through the front door.”

But what about dentists who, for whatever reason, discourage sharpening or think it damages instruments? One respondent said it was a “corporate policy” at her workplace that instruments were sharpened only one time a year. Another said, “My boss said I sharpen too often and that I would have to buy my own instruments if I wear them down too fast.” A few mentioned that during downtime, the doctor wanted them doing other things, such as recare calls. Another reported that her dentist “did not allow it.”

What does a dentist have to say about this behavior from his peers? “Dentists who discourage sharpening are just dead wrong,” says Chris Salierno, DDS, chief editor of Dental Economics. “A duller instrument will take longer to remove calculus than a sharper one; that’s self evident. If you sharpen an instrument enough, eventually you’ll need to replace it; that’s the cost of doing business.

“If a dentist gives you a hard time about sharpening and replacing instruments, a good strategy is to put it into terms that they can relate to. They replace dull handpiece burs, don’t they? If the dentist is just being cheap, look at the cost of a new scaler versus the fee for a scaling and root planing. Sharp scalers pay for themselves.”

The time management

It’s one thing to understand why sharpening is important to the business of a practice, but it’s entirely another to find time in your daily workflow to make it happen. Tim Irwin, a vice president at Nordent Instruments who has been teaching hand sharpening continuing education for more than 20 years, has seen the evolution of the hygiene appointment during the past two decades. Even 20 years ago, hygienists still struggled to find time, he says, but now? Forget about it.

Many hygienists tell him that they get to sharpen when they have a cancellation, but increasingly, employers are asking hygienists to do other things during these times, such as recalls. “So, if hygienists plan on sharpening during a cancellation, it is generally not the first cancellation or the fifth or the eighth, and many report that they are only really able to sharpen each instrument a couple of times a year,” he says.

Besides, unfilled cancellations can be very costly to practices and to hygienists if they are operating on a commission structure. So it stands to reason that using cancellations as a time to sharpen is both unreliable and expensive.

“There are just so many pressures on [hygienists’] time, they don’t have a realistic way to stick to a regular sharpening schedule,” says Irwin. So clearly another way is needed.

One solution is chosing a particular method of sharpening and becoming proficient in it. Watterson shared how she made sharpening more manageable: “When hygienists use handpiece sharpening, they can quickly and easily sharpen as needed by keeping the handpiece on their unit and ready to use. By keeping instruments sharp and not allowing them to become extremely dull, sharpening is an easy and quick chore.

“Before I learned handpiece sharpening, I tried to start my week off by coming in a few minutes early on Monday morning to get my instrument sets sharp. But as every hygienist knows, instruments become dull with use. So if the hygienist does not have enough sets of instruments, she will use the ones she has more often, which necessitates more frequent sharpening.”

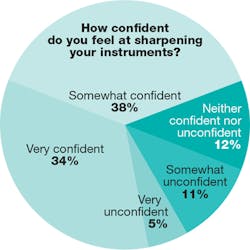

A significant portion of hygienists responding to our survey (40%) felt only “somewhat confident” at sharpening. Fifteen percent said that their biggest obstacle to sharpening was that they were simply not proficient. So while it’s not a panacea, taking time to become better at the nuts and bolts of your chosen sharpening method through practice or continuing education can help make the process faster and easier to incorporate into your day (or week, or month, depending on how many instruments you have access to). A few hygienists, 5% of our respondents, took advantage of a sharpening service, which is another helpful option for those pressed for time.

Conclusion

When hygienists understand their role as revenue generators in a practice, they can be empowered to advocate for their interests and their patients’ interests in a new way. A seemingly minor chore such as instrument sharpening is an important part of not only the hygienist’s clinical performance, but also to the business of a practice as well, and should be treated as such.

Amelia Williamson DeStefano, MA, is one of the managing editors of RDH magazine. She also works on RDH eVillage and Dental Economics.

About the Author

Amelia Williamson DeStefano, MA

Amelia Williamson DeStefano, MA, is group editorial director of the Endeavor Business Media Dental Group, where she leads the publication of high-quality content that empowers oral-health professionals to advance patient well-being, succeed in business, and cultivate professional joy and fulfillment. She holds a master's in English Literature from the University of Tulsa and has worked in dental media since 2015.

Updated May 16, 2023