Diet Assessment

You are in a unique position to offer counseling on simple dietary alterations

Dental hygienists can put their knowledge of nutrition to good use during clinical time by guiding clients toward good eating habits. Numerous fad diets in the marketplace are preferred by many people due to the simplicity of the rules and often for the promise of quick weight loss.

But is weight loss a preferred outcome of a healthy diet? Only if the person choosing the diet is overweight and the resulting weight loss is a loss of excessive adipose tissue. In order to help clients choose eating habits, dental hygienists should be able to recognize the benefits and weaknesses of a diet.

Hammock1 expresses a common misconception when she asserts, “You don’t have to change your life to change your waistline.” However, she refers to avoiding all carbohydrates, fats, or alcohol as the criteria for the changes that dramatically affect a lifestyle and suggests a 20 percent calorie reduction as an alternative by reducing the amount of food or substituting foods with fewer calories. The alternative is indeed the healthy and sustainable program, which is part of a lifestyle change, while avoiding carbohydrates or fats is necessarily a temporary change that does not become incorporated into life.

Kiley2 identifies the success of diet companies that sell the company’s manufactured foods as an integral part of consumers’ diet plans. The customers use the company’s prepackaged, nutritious meals and snacks while losing weight, but they often revert to larger meals when they have reached their goals. Clients have a high success rate at losing weight, but for long-term weight control, they would be better off with smaller portions of their own fresh foods.

On the other hand, Serafin3 emphasizes the success that both a diet company and its consumers can enjoy is when the company eases consumers’ transition into a healthy lifestyle, including diets. Such companies do not require in-house meetings or the use of specific products. Staying power and long-term customers come from the increased likelihood that excess fat will stay off for the long haul.

The U.S. Departments of Health and Human Services and Agriculture4 examine scientific data to create Dietary Guidelines aimed at a variety of professionals including health professionals whose work includes nutritional counseling. The value of enlisting health professionals to this cause is the number of diseases associated with poor diet and insufficient physical activity: “cardiovascular disease, hypertension, dyslipidemia, type 2 diabetes, overweight and obesity, osteoporosis, constipation, diverticular disease, iron deficiency anemia, oral disease, malnutrition, and some cancers.”

Studies ending in 1994 and 2002 showed a trend of increasing numbers of overweight and obese Americans. Overweight adults increased from 56 percent to 65 percent of the population and obesity increased from 23 percent of the population in the earlier study to 30 percent in the more recent one. The more recent study identifies 16 percent of Americans aged 6 to 19 being overweight.

In a given year, the mortality of men over 45 years old could be reduced by 16 percent, and of women in the same age group, mortality could be reduced by 9 percent if all Americans followed the U.S. Dietary Guidelines.

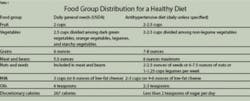

Specifically, the HHS and USDA recommend 1.5 to 2.5 times current consumption of fruits, vegetables, and dairy products. Whole grains and dark green and orange vegetables should be more than three times current consumption levels. Likewise, Americans need to make large decreases in enriched grains, solid fats, and sugars in their diets. On average, men should be reducing meats and oils, while women should be reducing starchy vegetables. Table 1 adapted from Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005 lists appropriate amounts of food groups based on a 2,000-calorie-per-day diet.

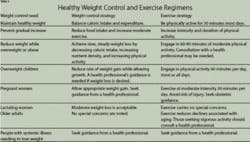

The HHS and USDA also point out that while exercise and a healthy diet (particularly control of calories) are important in both maintaining weight and losing weight, those behaviors need more rigor when weight loss is a goal. Initial restriction of caloric intake to lose weight is typically five to 10 times that for maintaining weight. Various weight control and physique needs can be achieved through the strategies in Table 2.

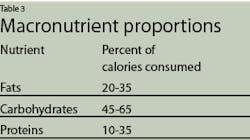

People need to be aware that over time, portion sizes have increased. Consumers might overlook this fact when reading nutrition labels without carefully examining that the serving size for which a particular number of calories noted does not necessarily equal the amount the consumer will actually eat. Further, the HHS and USDA recommend the proportions of macronutrients listed in Table 3.

Following these proportions helps to ensure the variety of micronutrients associated with the macronutrients. In addition, the HHS and USDA stress that weight control depends on total calorie intake and expenditure as part of a healthy lifestyle, rather than the proportions of macronutrients, reflecting the weakness of diet fads that focus on restricting or reinforcing a particular food or food group.

Indeed, energy expenditure is so important to maintaining health along with eating habits that the dietary guidelines now include physical activity. Medical experts now recognize that moderate to high intensity exercise should be an almost daily activity for most people. People should work even short periods of physical activity into their schedules. Incidentally, short walks at a sedentary job do not provide significant benefits to this end. Exercise should include aerobic, anaerobic, and flexibility activities.

The HHS and USDA suggest that health professionals in the United States encourage their clients to eat more “fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and fat-free or low-fat” dairy products. In contrast, most Americans should not increase their protein consumption.

People eating larger amounts of fruits and vegetables have a lower risk of stroke, type 2 diabetes, and cancers in the respiratory and digestive tracts. Dairy products protect bone mass, and fiber “may reduce the risk of coronary heart disease,” yet bleached wheat, which is popular in soft, white bread, has little fiber left in it. Appropriate amounts of fat are vital to absorption and assimilation of essential nutrients while protecting the cardiovascular system from excessive lipidemia and the body from excess calories.

A larger proportion of the fat that is being consumed should be in the form of unsaturated fats, with particular attention to the avoidance of trans-fatty acids. This is best accomplished by eating fish and foods with liquid fats from plant products rather than solid fats that come from mammalian meats and processing. For a 2,000-calorie diet, no more than 20 grams should be from saturated fat.

Sugar and starch become glucose in the body’s metabolism and have the same metabolic effects once in the body regardless of their source, but foods with added sugars have empty calories - low nutrient density for the amount of food consumed. Glucose is particularly important for blood and brain function.

Like sugar, sodium is a common additive to foods during processing and at the table. Excessive sodium and insufficient potassium intake are common among Americans and lead to hypertension. Consumers can reverse these trends by reading nutrition labels and reducing the salt they add to foods during cooking and eating. Also, like added sugar, alcohol is typically empty calories; however, drinking up to two alcoholic beverages per day is associated with the lowest mortality rate, as compared with heavy or no alcohol consumption.

Diets low in carbohydrates are popular nowadays for reducing weight. The deficiency in carbohydrates leads to several problems. Bryngelsson and Asp5 point out that a typical diet should have 130 grams of carbohydrates per day to accommodate the need for metabolism. When there is an insufficient amount of carbohydrates, the body can use glycogen stored in the liver, but this reserve can last for only 24 hours. The body can also obtain glycogen from muscle tissue transported to the liver as alanine and lactate. Again, this is a small store of carbohydrate substrate. One further source of carbohydrates is from muscle or food protein transformed to glucose through gluconeogenesis. The resulting loss of muscle leads to weakness and further lowering of metabolism.

Bryngelsson and Asp explain that continued restriction of carbohydrates leads to ketosis. The deficiency of glucose in the body leads to inefficient metabolism of fatty acids in the Krebs cycle. The resulting unmetabolized acetyl-coenzyme A forms acetoacetate, hydroxybutyrate, and acetone, known collectively as ketone bodies. These ketone bodies are a secondary source of energy for our metabolism that can help to prevent loss of muscle mass, but ketosis itself has hazards. These include reduced calcium in bones, increased risk of kidney stones, brain dysfunction, and in the case of substituting carbohydrates with saturated fat, increased cholesterol levels. The weight reduction phase of low-carbohydrate diets does reduce low-density lipoproteins; however, this does not accommodate for the long-term damaging effects.

Insufficient fiber, a common characteristic of low-carbohydrate diets, may also lead to eating more food (thereby more calories). Fiber provides a sense of fullness when eating. Substituting excessive amounts of protein to replace carbohydrates can lead to kidney dysfunction and loss of minerals from bones. The initial phase of weight loss in low-carbohydrate diets appears to be due to loss of glycogen and water rather than loss of fat. If weight loss continues, it is due to reduced calorie intake, which can be accomplished more safely with a balanced, reduced-calorie diet.

Ultimately, any diet can result in weight loss if calorie intake is less than calorie expenditure, but sustained maintenance of healthy weight requires a diet that contains healthy proportions of macronutrients both for proper metabolism of those nutrients and for their properties as carriers of micronutrients. Otherwise, people using those diets suffer from nutritional deficiencies or revert to their prior dietary habits.

Nutritional aberrations have manifestations on oral and perioral structures, making dental hygienists’ understanding, assessment, and counseling of clients’ dietary habits a valuable part of clinical practice. Hygienists can use a food diary recorded by the client to assess the client’s diet. Clients whose diets differ greatly from the proportions listed in Tables 1 and 3 are likely to have an imbalance in nutrients.

Dental hygienists can offer counseling on simple dietary alterations and refer the client to a dietetics professional when a client’s counseling needs are more complex or the client has systemic complications, which may affect dietary needs. Like dental hygiene, nutrition best serves people through promoting health. Dental hygienists’ expertise and frequent contact with clients provide many opportunities for health promotion through diet.

References

1 Hammock DA. (2005, November). The easiest way to lose weight. Good Housekeeping, 241(5), 215-216.

2 Kiley D. (2005, September 19). My dinner with NutriSystem. Business Week, p. 84.

3 Serafin T. (2006, April 10). Fat of the Land. Forbes, 177(7), 104.

4 US Department of Health and Human Services and US Department of Agriculture. (2005). Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005, 6th ed. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

5 Bryngelsson S., & Asp NG. (2005). Popular diets, body weight and health: What is scientifically documented? Scandinavian Journal of Nutrition, 49(1), 15-20.

Howard M Notgarnie, RDH, MA, practices dental hygiene in Colorado, and has eight years’ experience in official positions in dental hygiene associations at the state and local levels.