The Internet ... as a research toolFinding the balance

by M. Elaine Parker, RDH, MS, PhD

Decisions are made daily about the many different therapies for patients. Frequently, our patients ask well-informed questions about these or other therapies available. Many of our recommendations are based on what we learned in college, the focus of our practice, the wide variety of products advertised on TV or in consumer magazines, as well as the technical research and abstracts published in professional journals. Continuing education courses and professional meetings present a tremendous opportunity to discuss the experiences and successes our peers have had with different therapies and to discover new products.

Resources for current information that have become much more accessible in the past several years are the various health-care search engines and libraries available on the Internet. Not only do we have access to this information but our patients also use this access to become more educated dental consumers than they were in the past. Because of this wealth of information, never before has there been such a need to keep up with the many facets of our profession. This need can only increase with time. This article will help the clinician keep abreast of the most current, credible scientific literature and how it applies to your practice.

As health-care providers, we have the desire to provide the best care and recommendations for our patients. Sometimes finding the balance between the available information on "best care and recommendations" from different — and sometimes contradictory — sources and what we observe with our patients presents a true challenge. We need to use our time wisely in order to become discriminating learners who provide research supported or "evidence-based health care" (EBHC). Learning to use research databases will allow us to be better equipped not only to critically observe our patients, but also evaluate research outcomes and decide how to use the information.

Evidence-based medicine (EBM) or EBHC was first described as "the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of the individual patient. It means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best external clinical evidence from systematic research."1 There has been a transition to a much-needed change from treatment based on our own (or our colleague's) individual clinical preference to EBHC.

The need for EBHC is clear and will provide supported treatment approaches now and in the future. Additionally, EBHC data can be useful for larger institutions such as governments, universities, and insurance companies for deciding treatment coverage, premiums, and documenting health-related demographics. Both patients and providers will benefit from more outcome-based studies conducted in the future, thereby contributing the best EBHC for our patients.

Where and how do we start using EBHC? Evidence-based medicine "converts the abstract exercise of reading and appraising the literature into the pragmatic process of using the literature to benefit individual patients while simultaneously expanding the clinician's knowledge base."2,3 Effective use of EBHC builds our knowledge one topic or patient at a time.

However, if we do not follow some basic guidelines, our search can be misleading or incorrect for the question we are trying to answer. We also must be mindful of who, how, and why some research is conducted and analyzed, as well as who is summarizing in a review and sponsoring the work.

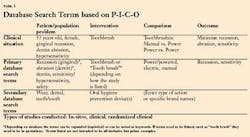

Several guidelines for EBHC are currently recommended. Each has common points that are essential, but they all start with a question related to a particular problem or population. Asking evidence-based questions in a P-I-C-O format identifies the:

• Patient, population, or problem

• Intervention

• Comparison(s) that are evaluated

• Outcomes of the intervention.

Also very important to know is that clinical experience, patient preference, and individual circumstances are essential parts of the equation.

Once all of this information is addressed, it helps form our clinical question and scenario before we begin a literature search strategy.3 For example, you have a 53-year-old patient who has recession, dentinal abrasion, and some sensitivity. She uses a manual toothbrush very aggressively when she demonstrates her brushing technique to you. She would like to start using a power toothbrush that will not add to her abrasion, recession, or sensitivity. The patient has had surgical root coverage and restorations to cover the abraded and recessed areas. She does not want further surgeries.

This is a fairly typical scenario. By following the P-I-C-O guidelines, you can establish the question to find evidence and recommendations (see Table 1). In addition, your overall experience and knowledge of your patient is extremely valuable and needs to be incorporated. You might know that her root coverage surgeries went well and improved her esthetics, covered large areas of exposed abraded dentin, and reduced the sensitivity for the teeth that were treated. Both of you would be very concerned if the success of these areas were not preserved. You know that she has moderate recession and minimal attached gingiva in several areas. She has used various dentifrices and medications for her hypersensitivity, with little success.

Your experience with several other patients in your practice has taught you that if she could reduce the pressure or trauma on her gingiva it might impact the recession, which in turn would expose less dentin. There is also a lot of other information which helps in filtering the information, such as judgments from your experience. Previous exams and treatments have helped to rule out clenching or bruxism, oral habits with objects, aggressive flossing, erosion from diet, or early cervical caries.

At first, this can seem like there is an overwhelming amount of information to help address your patient's concerns. Using P-I-C-O as noted — and considering what information you need to address with your question — one P-I-C-O question could be, "For patients with dentinal sensitivity, does brushing with a powered toothbrush in comparison to a manual toothbrush prevent further abrasion and decrease sensitivity?"

Since we know that exposed dentin can be very sensitive, another more specific question would be, "For patients with exposed dentin would brushing with a powered toothbrush in comparison to a manual toothbrush prevent further recession (dentin abrasion)?"

The next step is to use descriptive terms from P-I-C-O and identify some alternative terms. For example, a study evaluating dentin could use teeth, tooth structure, clinical crown, etc. With this information you can begin an efficient, informative search. In performing the search, you want to enter the terms that describe the clinical situation, P-I-C-O. For the example, the primary terms abrasion/dentin (P), toothbrush (I), and powered (C), the outcome (O) is what needs to be determined.

The next step is to choose a database you want to use; some of them will contain different information, and different ways to search. Most of these databases have tutorials. PubMed, the public version of MEDLINE, has two ways it can be accessed, directly or through OVID, a medical information service. Both of these have tutorials online at http://www.nlm.nih.gov/bsd/pubmed_tutori al/m1001.html and http://www.mclibrary.duke.edu/ respub/guides/ovidtut. In PubMed, you can start your search with the broader terms and then help narrow the search with P-I-C-O. For example, the search number and the term show that for "dentin" there were 14,352 items found. The results after using various terms from the P-I-C-O equation yielded the following:

• One citation from "search dentin AND abrasion AND toothbrush AND power"

• 20 citations from "search dentin AND abrasion AND toothbrush"

•111 citiations from "search abrasion AND toothbrush"

• 407 citations from "search dentin AND abrasion"

•14,352 citations from "search dentin"

The citation retrieved through the narrowed parameters referred to measuring dentin substrate wear associated with toothbrushes. In vitro specimens simulated clinical sutations. "The specimens were brushed for the equivalent of the amount of time an individual tooth surface would be brushed in a 2-year period using a machine that simulated typical movement of a toothbrush across the specimen under controlled load and fluid conditions." Brushing was done with both manual and powered toothbrushes. The results reported measurements of dentin substrate wear in both average depth and average maximum depth measurements.4

It is occasionally good to review the longer list of the 20 articles to see if they can be helpful for your patient. It is also sometimes very helpful to refine the search terms. You can make a change to reflect that by "dentin and abrasion and toothbrush and power not dentifrice." In this example, it reduces the hits from 20 to eight studies that could be relevant. Reviewing the title lines for the items found could identify those studies that can potentially help.

In this P-I-C-O there are two terms: dentin and abrasion. Since some studies might not identify dentin abrasion and just note it as abrasion or tooth abrasion, it is good to enter these terms as well. If "abrasion and toothbrush not dentifrice" are entered, 69 articles are found. When "tooth and abrasion and recession and toothbrush not dentifrice" are entered, 11 items are found most of which could be relevant depending on how the study was structured and conducted and the analysis is credible.

Depending on the database or library that you use, you could choose to recover a bibliography list, abstracts, or full articles or reviews. Through the National Library of Medicine (NLM) many catalog and databases are available. The most noted of these is MEDLINE; others are MEDLINEplus (for consumers), PubMed or MeSH. MeSH or Medical Subject Headings uses an established hierarchy of specific assigned descriptors and qualifiers, through a controlled vocabulary, and supplementary concepts that are used for indexing. Even though it is also thorough the NLM it does not connect to MEDLINE database nor is it a substitute for PubMed.

MeSH is more difficult to learn and to use the proper vocabulary. However, MeSH can be navigated through a tree structure. Although not particularly "user friendly," MeSH can be much more consistent and reliable than other databases that have a wide range of terms that can be entered. If you are experienced with doing searches for literature reviews, you may find this very beneficial. As you gain more experience, certain functions help conserve your valuable time on any of these databases.

Some databases have free access while others have subscription fees. Patient Oriented Evidence that Matters (POEMS) at www.ebponline.net and Clinical Evidence at www.clinicalevidence.com are just two sites that have a subscription fee. In general, the fee-based databases provide a report from their systematic review and analysis process. Some of these reviews are independent or some organizations and companies requesting the review sponsor this effort.

A very good resource for those who have not been involved with research or who have not critically read studies for some time, or just want some more information, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) provides a site at http://clinicaltrials.gov/ that outlines different types of clinical studies. Titled "Understanding Clinical Trials," this site provides very good information and clear insight into protocols, sponsors, controls, etc.

Additionally, a brief overview of research can be found on the Web site of State University of New York (SUNY) Downstate Medical Center Evidence Based Medicine Course (http://servers.medlib.hscbklyn.edu/ebm/toc. html).

As a side note, if you need to research information on patients with special needs or a defined systemic problem, the Combined Health Information Database (CHID) utilizes 16 databases that can also be searched individually (http://chid.nih.gov/help/help.html). This site can also be found through Oral Health Database, which has information on health promotion and educational materials not indexed elsewhere.

This resource also has copies of product information material that has been produced by manufacturers and non-NIH organizations. However, while CHID is a database that provides bibliographic, abstract, and information availability, it does not contain the articles themselves. CHID also provides an easy to understand explanation on how to do a search.

One area of research that is often missing or considered irrelevant to actual patient care is the in-vitro or laboratory experiment. Critical information is discovered and answered in these kinds of studies. Results from these in-vitro studies are key to developing pre-clinical and clinical studies. They also provide information that needs to be considered or observed in a clinical study.

Keep in mind that a company needs to perform in-vitro tests to help develop new products and to test products in a controlled setting that answers how a product performs during a specific task. These in-vitro tests are needed when a clinical study is very difficult to control because of a multitude of things that could impact the study, or are very difficult to precisely measure in a mouth or on a model — both of which could lead to a study with ambiguous findings.

When looking for specific performance outcomes, do not exclude in-vitro or laboratory tests. They might have much less confounding information. Besides, in-vitro studies are a very good method to compare products side by side to evaluate how they really perform in a well-controlled environment. For example, testing marginal wear on restorations or abrasion is well suited for laboratory testing. The results are more accurate than the variability that can be generated from subjects' compliance and consistency, not to mention the measurement error that could occur from taking these difficult clinical measurements.

Both clinical studies and laboratory studies can offer valuable information. It is important to look at the information your search yields and determine what information or article(s) are beneficial to the needs of your patient. Spending more time reading the complete article rather than just an abstract or ad line can help you find the right information, not just information.

Adding to the difficulty of solving the research puzzle is that certain treatments or products are often repeatedly studied over a period of time, as well as being conducted at different sites or even by the same investigators at different times with differing results. One way these studies are evaluated is to have a panel do a systematic review of the primary studies that show evidence of how the study was conducted and analyzed. This review is summarized according to a method that is reproducible. A meta-analysis is a similar summary of studies that have some similarity in statistics used and meet predetermined criteria to be evaluated.

However, this analysis might not account for a well designed and conducted clinical study because of the criteria selected for the meta-analysis. If there are tremendously more studies conducted on one intervention more than another, it could have some impact on the analysis. If a treatment has been studied for years — such as with plaque removal or manual toothbrushes — newer (powered toothbrushes) or cutting edge technologies (devices to measure plaque biofilm) are fewer in number.

Considering the speed at which information is changing, utilizing resources such as the Internet to incorporate new clinical information into daily patient care is essential. Learning to form P-I-C-O questions to determine the parameters of a search regarding a particular clinical situation and using various Internet databases allows the clinician to obtain information in a timely fashion. Using the evidence from various types of research including in-vitro and in-vivo studies, in combination with our clinical preferences and experiences will provide our clients with the state-of-the-art oral healthcare.

M. Elaine Parker, RDH, MS, PhD, is an associate professor and graduate program director at the Department of Dental Hygiene, Baltimore College of Dental Surgery Dental School, University of Maryland.

References1. Sackett, D. Evidence-based Medicine: How to Practice and Teach EBM. 2nd edition. Churchill Livingtone, 2000

2. Bordley DR. Evidence-based medicine: a powerful educational tool for clerkship education. American Journal of Medicine. 102(5):427-32, 1997 May

3. UNC-Chapel Hill, HSL, Database Searching learning module: http://www.hsl.unc.edu/lm/degrant/introduction.htmhttp://www.hsl.unc.edu/lm/degrant/introduction.htm

4. Sorensen JA, Mguyen H, Oregon Health and Science University, Am J Dent 2002; 15 (Special Issue): 26B-32B