Ergonomic synergy: Creating a functional, low-stress workspace

Since appearing just over 70 years ago, ergonomics has landed in the top 1% of most used words.1 When it comes to workplace tools, devices should be designed to adapt to the user and not the other way around.2 Marketing initiatives often use the word ergonomic without a full appreciation of what it actually means in a specific setting. And purchasers often assume there is truth behind this “feel-good” adjective.

Our most critical tool is a healthy body. Both brick-and-mortar dental offices and remote delivery settings, can create enormous physical strain. Many clinicians assume pain and injuries are inevitable, and sadly some feel powerless to ask for changes that can reduce the risk of developing a workplace-related musculoskeletal disorder.

Everyday life can also add stress on our bodies. Hidden sources of physical stress include household cleaning and cooking, childcare, time in the car, and household maintenance. The increased use of digital devices has had a huge impact on neck and shoulder posture,3-5 and puts great strain on the hands, most particularly the thumb.6

Society has become more sedentary, with long stretches of sitting while commuting to work. Studies show workers now sit for extended periods of time using poor postures.7 So how we live and play have the potential to increase the stress the workplace can place on our bodies.

How injuries begin

The spine is not a straight stick, but rather a chain of flexible bones. The neck is the most flexible part of the spine. A healthy spine contains four structural curves. Spinal curves provide stability and support the human torso and the weight of the head and arms.

The cervical and lumbar curves in the spine are architectural wonders: the cervical curve supports the head, and the lumbar curve supports the pelvis. Spinal discs and ligaments provide elasticity. The spine also works with with muscles, tendons, and ligaments to allow movement in all directions.8 When the skeletal system works in harmony with the body’s soft tissue, life is good.

The seeds of trouble are sown when the human body is subjected to static postures or awkward positions for hours on end. Our musculoskeletal system is not designed for continuous stress. Over time, muscles get sore and stiff, bones begin to remodel, tendons and ligaments get damaged, and the intervertebral discs in the spine fail to provide adequate support. Inadequate rest or insufficient breaks further compound the problem. Even at a cellular level, the body needs time to rest and repair.

It is impossible to sit perfectly upright while providing clinical care, but the goal is to minimize movements, such as unnecessary reaches or bends, to no more than 20° from neutral.9 This is possible, but it requires a thorough understanding of how to work smarter, how equipment and positioning impact the musculoskeletal system, and a willingness to work with equipment that minimizes physical stress.

There are very few comprehensive studies of injury rates, and while it is difficult to compare the findings of one study to another, the injury rates are alarming over the lifespan of our clinical careers.10-14 In a 2012 survey involving 1,217 clinicians, the number of years in practice ranged from 1 to over 40. Neck injuries were the most common (63%), followed by shoulder (54%), lower back (36%), and mid/upper back (28%). The data for those practicing 10 years or fewer revealed startling information. Those who had practiced less than 1 year were already reporting pain in these areas, and the relative risk for developing issues doubled or tripled during the first 10 years. These sobering statistics are supported by a number of other studies.15

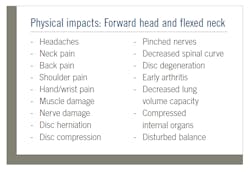

In response to poor upper body postures, the vertebrae in the spinal column begin to compensate. As the disc space changes, the intervertebral pressures become uneven, resulting in stiffness and pain,8 setting the stage for a compromised airway.16 To compensate for these imbalances, muscles and ligaments either become tight and short or are literally stretched beyond their natural limits. This sets the stage for the remodeling process. The vertebrae shift position, discs herniate, and bone spurs develop. Over time the cervical curve in the neck is lost as the vertebrae move and the neck becomes straighter.17-19

The so-called hygiene hump, the big, rounded bulge on the back of so many clinicians’ necks, is a perfect example of how the body responds to repeated trauma over time. By the time the hump appears, significant damage is already occurring.

Shoulders should be relaxed, not rounded forward.20 It’s easy to see postural compromises when looking at the body from the side. Forward head postures lead to tight chest muscles and long, strong, aching back and neck muscles, resulting in a medical condition known as Upper Crossed Syndrome.20

Muscle fatigue is not the only issue. Research indicates a huge range of problems that can include a reduction in respiratory volume as high as 30%.21-25 Digestion can also be impacted, and headaches are also a frequent complaint.

Healthy workspace principles

Every clinician, patient, treatment room, and chair is different. There are enormous challenges in creating a treatment space that will allow multiple clinicians to work safely. Considering basic ergonomic principles can help support a less stressful clinical posture by reducing awkward postures, excessive reaching, and repetitive motions. It is important to minimize how your body adapts to the workspace.26 While it is impossible to control all variables, a mindful approach can help reduce the risks.

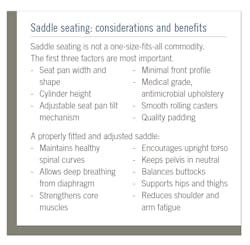

Position the patient’s head so the mouth is close and easy to reach. For a seated clinician, this means having their mouth at waist level, so the forearm is positioned parallel to the floor. This eliminates shoulder abduction, the source of the dangerous “chicken wing” posture. A fully adjustable saddle stool with the correct cylinder length allows clinicians to adjust the height of the patient chair according to each patient.27-29

Tools that are used frequently should be placed as close to the work area as possible. This minimizes unnecessary twisting and turning, or excessive reaching. Rear delivery systems are designed for an assisted clinician, not those who work solo. This particular treatment room configuration increases the risk for significant shoulder injuries.

Saddles designed for workers in the beauty industry often feature a large prominence at the front. This bulk increases the distance to the workspace, and also increases pelvic pressure as dental clinicians lean their upper body forward to treat patients.30

Rather than use a traditional seating postures that position the thighs parallel to the floor, some clinicians are standing for care. They report less lower back pain and overall fatigue, but it is important to consider the long-range impact on the hips, knees, and ankles. A properly fitted and adjusted saddle allows the user to assume a neutral supported posture that uses the spine to hold the torso erect.

Until loupes and headlights became commonplace, clinicians were forced to contort their bodies into pretzel-like positions while straining to get a good view. Loupes and lights are not magic; they are tools that work well if properly adjusted for the user. The working distance and declination angle need to be correctly measured for each individual in order to obtain an ideal posture. The head remains erect, with minimal forward head posture and little neck flexion. When the ear is positioned over the shoulder, the cervical curve in the spine can support the weight of the head.31,32 Auxiliary headlights not only illuminate the work area, but also eliminate dangerous, repetitive reaches, and can reduce eye fatigue.

Face shields, once considered optional by many, are now common. There are a number of features to consider when selecting a shield including the weight, how the shield is worn, quality of the plastic, and potential glare or reflection. Shields can be attached to either rigid or adjustable headbands or clipped on to the temple arms on a pair of loupes or safety glasses. It is important to find a shield that fits the clinician’s head shape and size, and also provides enough room for magnification and illumination devices.

You preach prevention. Practice it, too. The system failures that arise when the human body is out of balance are shocking. Recovery from a cumulative trauma disorder can be a daunting task. There is simply no guarantee that the damage can be reversed. It is wise to adopt and implement preventive strategies as soon as possible in one’s career.

References

- Ergonomics. Merriam-Webster. Updated January 23, 2021. Accessed February 25, 2021. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ergonomics#h1

- Middlesworth M. ErgoPlus. Ergonomics 101: The definition, domains, and applications of ergonomics. Published March 7, 2020. https://ergo-plus.com/ergonomics-definition-domains-applications/

- Alsalameh AM, Harisi MJ, Alduayji MA, Almutham AA, Mahmood FM. Evaluating the relationship between smartphone addiction/overuse and musculoskeletal pain among medical students at Qassim University. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8(9):2953-2959. doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_665_19

- Yoon W, Choi S, Han H, Shin G. Neck muscular load when using a smartphone while sitting, standing, and walking. Hum Factors. 2020:18720820904237. doi:10.1177/0018720820904237

- Xie Y, Szeto GP, Dai J, Madeleine P. A comparison of muscle activity in using touchscreen smartphone among young people with and without chronic neck-shoulder pain. Ergonomics. 2016;59(1):61-72. doi:10.1080/00140139.2015.1056237

- Baabdullah A, Bokhary D, Kabli Y, Saggaf O, Daiwali M, Hamdi A. The association between smartphone addiction and thumb/wrist pain: A cross-sectional study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(10):e19124. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000019124

- Turci AM, Gorla C, Bersanetti MB. Assessment of arm, neck and shoulder complaints and scapular static malposition among computer users. Rev Bras Med Trab. 2019;17(4):465-472. doi:10.5327/Z1679443520190329

- Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care. How does the spine work? Informed Health. Published February 14, 2009. Last Update February 14, 2019. Assessed February 27, 2021. https://www.informedhealth.org/how-does-the-spine-work.html

- Namwongsa S, Puntumetakul R, Neubert MS, Boucaut R. Effect of neck flexion angles on neck muscle activity among smartphone users with and without neck pain. Ergonomics. 2019;62(12):1524-1533. doi:10.1080/00140139.2019.1661525

- Radanovi´c B, Vucˇinic´ P, Jankovic´ T, Mahmutovic´ E, Penjaškovic´ D. Musculoskeletal symptoms of the neck and shoulder among dental practitioners. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2017;30(4):675-679. doi:10.3233/BMR-150508

- Šc´epanovic´ D, Klavs T, Verdenik I, Oblak Cˇ. The prevalence of musculoskeletal pain of dental workers employed in Slovenia. Workplace Health Saf. 2019;67(9):461-469. doi:10.1177/2165079919848137

- Lietz J, Kozak A, Nienhaus A. Prevalence and occupational risk factors of musculoskeletal diseases and pain among dental professionals in Western countries: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0208628. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0208628

- 2015 Dentist well-being survey report. ADA 2017. ADA Center for Professional Success. Published 2017. Accessed February 27, 2021. https://ebusiness.ada.org/assets/docs/32944.PDF?OrderID=1364096

- Shekhawat KS, Chauhan A, Sakthidevi S, Nimbeni B, Golai S, Stephen L. Work-related musculoskeletal pain and its self-reported impact among practicing dentists in Puducherry, India. Indian J Dent Res. 2020;31(3):354-357. doi:10.4103/ijdr.IJDR_352_18

- Guignon AN, Purdy CM. Dental hygiene practice in North America. The physical, economic, and workforce impact of musculoskeletal disorders among dental hygienists. Poster presented at: ADHA Annual Session; June 2014, Las Vegas, NV.

- Attali V, Clavel L, Rémy-Neris S, Skalli W, et al. Cervical spine hyperextension and altered posturo-respiratory coupling in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Front Med (Lausanne). 2020;7:30. doi:10.3389/fmed.2020.00030

- Sun A, Yeo HG, Kim TU, Hyun JK, Kim JY. Radiologic assessment of forward head posture and its relation to myofascial pain syndrome. Ann Rehabil Med. 2014;38(6):821-6. doi:10.5535/arm.2014.38.6.821

- Silva AG, Punt TD, Sharples P, Vilas-Boas JP, Johnson MI. Head posture and neck pain of chronic nontraumatic origin: a comparison between patients and pain persons. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(4):669-74.

- Mahmoud NF, Hassan KA, Abdelmajeed SF, Moustafa IM, Silva AG. The relationship between forward head posture and neck pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2019;12(4):562-577. doi:10.1007/s12178-019-09594-y

- Thigpen CA, Padua DA, Michener LA, et al. Head and shoulder posture affect scapular mechanics and muscle activity in overhead tasks. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2010;20(4):701-9. doi:10.1016/j.jelekin.2009.12.003

- Mujawar JC, Sagar JH. Prevalence of upper cross syndrome in laundry workers. Indian J Occup Environ Med. 2019;23(1):54-56. doi: 10.4103/ijoem.IJOEM_169_18

- Szczygieł E, Zielonka K, Me˛tel S, Golec J. Musculo-skeletal and pulmonary effects of sitting position - a systematic review. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2017;24(1):8-12. doi:10.5604/12321966.1227647

- Cheon JH, Lim NN, Lee GS, et al. Differences of spinal curvature, thoracic mobility, and respiratory strength between chronic neck pain patients and people without cervical pain. Ann Rehabil Med. 2020;44(1):58-68. doi:10.5535/arm.2020.44.1.58

- Wirth B, Amstalden M, Perk M, Boutellier U, Humphreys BK. Respiratory dysfunction in patients with chronic neck pain - influence of thoracic spine and chest mobility. Man Ther. 2014;19(5):440-4. doi:10.1016/j.math.2014.04.011

- Solakog˘lu Ö, Yalçın P, Dinçer G. The effects of forward head posture on expiratory muscle strength in chronic neck pain patients: A cross-sectional study. Turk J Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;66(2):161-168. doi:10.5606/tftrd.2020.3153

- Lietz J, Ulusoy N, Nienhaus A. Prevention of musculoskeletal diseases and pain among dental professionals through ergonomic interventions: a systematic literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(10):3482. doi:10.3390/ijerph17103482

- García-Vidal JA, López-Nicolás M, Sánchez-Sobrado AC, et al. The combination of different ergonomic supports during dental procedures reduces the muscle activity of the neck and shoulder. J Clin Med. 2019;8(8):1230. doi:10.3390/jcm8081230.

- Plessas A, Bernardes Delgado M. The role of ergonomic saddle seats and magnification loupes in the prevention of musculoskeletal disorders. A systematic review. Int J Dent Hyg. 2018;16(4):430-440. doi:10.1111/idh.12327

- Purdy C. Adjusting a saddle stool. YouTube. Published February 10, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oEDDgAP3Ctk

- Guignon AN. Take a stand on seating; strategies defuse occupational hazards associated with sedentary positions. RDH. Published September 19, 2016. Accessed February 25, 2021. https://www.rdhmag.com/patient-care/article/16409230/take-a-stand-on-seating-strategies-defuse-occupational-hazards-associated-with-sedentary-positions

- Ludwig EA, Tolle SL, Jenkins E, Russell D. Magnification loupes influence on neck and trunk flexion of dental hygienists while scaling-A pilot study. Int J Dent Hyg. 2021;19(1):106-113. doi:10.1111/idh.12470

- Carpentier M, Aubeux D, Armengol V, Pérez F, Prud’homme T, Gaudin A. The effect of magnification loupes on spontaneous posture change of dental students during preclinical restorative training. J Dent Educ. 2019;83(4):407-415. doi:10.21815/JDE.019.044

ANNE NUGENT GUIGNON, MPH, RDH, CSP, has received numerous accolades over four decades for mentoring, research, and guiding her profession. As an international speaker and prolific author, Guignon focuses is on the oral microbiome, erosion, hypersensitivity, salivary dysfunction, ergonomics, and employee law issues. She may be contacted at [email protected].

About the Author

Anne Nugent Guignon, MPH, RDH, CSP

ANNE NUGENT GUIGNON, MPH, RDH, CSP, has received numerous accolades over four decades for mentoring, research, and guiding her profession. As an international speaker and prolific author, Guignon focuses is on the oral microbiome, erosion, hypersensitivity, salivary dysfunction, ergonomics, and employee law issues. She may be contacted at [email protected].