White sponge nevus

BY NANCY W. BURKHART, BSDH, EdD

White sponge nevus is a disease component of a group of inherited diseases that produce a white, bilateral, keratinized appearance typically appearing on the buccal mucosa. The term used for this type of genetically induced lesion within the family of white lesions is genokeratoses. White sponge nevus (WSN) is an autosomal-dominant disease that is caused by the mutation of certain keratin genes.

Keratin is the structural protein of epithelial cells. There is a defect in the normal keratinization (keratin 4 and keratin 13) that is expressed in the suprabasal keratinocytes of the buccal, nasal, esophageal mucosa, and anogenital tissue. The disorder is also most commonly known as familial, white-folded mucosal dysplasia, hereditary leukokeratosis, exfoliative leukoedema, and as Cannon's disease (described in 1909 by Hyde and given the name in 1935 by A. B. Cannon).

Although a diagnosis is usually provided in childhood, patients may exhibit a milder form in their early years, and the disorder may be diagnosed in the adult much later. Although rare, occurring in less than 1 in 200,000, in recent years families have become more aware of the genetic link to WSN. With improved pediatric health histories, the genetic factor is usually recognized early in life.

Clinical appearance: The patient will exhibit heavy white plaques mainly on the buccal and labial mucosa that are asymptomatic. The white plaques may also appear on the floor of the mouth, tongue, and alveolar mucosa with rare occurrence on the palate. Heavy, thickened tissue may compromise mastication. Less common areas such as nasal, esophageal, laryngeal, and anogenital mucosa may be affected.

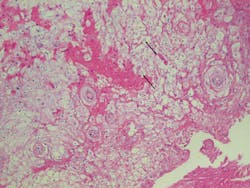

When viewed microscopically, the tissue exhibits acanthosis or a heavy thickening of the prickle cell layer of the epithelium. This promotes the thick white appearance that is very characteristic of WSN. Another feature noted is the cytoplasmic clearing of the epithelial cells that a pathologist will recognize.

Differential diagnosis: The clinician would initially rule out:

• Leukoplakia

• Leukoedema

• Lichen planus

• Tobacco-related damage to the tissue, such as spit tobacco and betel quid

• Chemical burns and temperature-related burns

• Candidiasis confirmed through culture (with Candida albicans, the clinician is able to wipe the white plaque from the tissue, but WSN will not wipe off with gauze)

• Morsicatio buccarum (carefully question the patient regarding this habit)

• Hereditary benign intraepithelial dyskeratosis (Witkop-von Sallman syndrome)

White Sponge Nevus. Courtesy of Doron Aframian, DMD, PhD.

Other white lesions that may be ruled out after a thorough review of the health history would include snuff dippers keratosis and oral submucous fibrosis. Since both of these are tobacco related, careful questioning of the patient should determine whether these habits would be at the top of your differential list.

Although the considerations listed above are probably most logical, oral cancer should never be discounted until proven otherwise. A biopsy is always needed in unconfirmed cases to rule out malignancy and other previously mentioned disorders.

An oral medicine perspective: When a definite diagnosis is made of WSN, the prognosis is excellent and no further treatment is needed for the oral lesions. Intervention may occur if the tissue is so thickened or dense that it begins to affect mastication for the patient.

Images courtesy of Murat Songu, MD, department of otorhinolaryngology, Dr. Behcet Uz Children's Hospital in Izmir, Turkey.

Some reported treatments within the literature that have shown improvement in some patients are various vitamins, antihistamines, chlorhexidine mouth rinses, some antibiotics, and nystatin. However, these results have been very limited and only beneficial for select patients. Some researchers believe that the altered tissues make fungus and bacteria more persistent and harbored within the tissues.

So if the condition is totally benign, why should the dental professional be concerned about the clinical appearance of white sponge nevus? The condition is often misdiagnosed, leading to unneeded treatment.

In some patients, the misdiagnosis leads to unnecessary surgery. Children have been treated for candidiasis with antifungal medications in order to treat the white plaques. When the areas do not subside, further testing is usually performed and ultimately discovered to be white sponge nevus. Reports of older adults are discussed in the literature, and these patients may not know that the white plaques are white sponge nevus. With adults, there is often a complaint of the esthetic issues involved with the appearance of the tongue, lips, or other oral tissue that is visible to others. There is also a reported altered texture of the tissues as thickness may increase over time.

Since WSN is usually diagnosed in childhood, the clinician may not even consider that the adult patient may be exhibiting signs of WSN. A detailed health history, knowledge of possible etiologies, and attentive listening skills will assist in the correct course of action for the practitioner.

As always, keep asking good questions and always listen to your patients. RDH

References

1. DeLong L, Burkhart NW. General and Oral Pathology for the Dental Hygienist. 2nd Ed. 2013; Wolters Kluwer Health:Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore.

2. Dadlani C, Mengden S, Kerr AR. (2008) White sponge nevus. Dermatology Online Journal, 14(5). Retrieved from: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/768308n1

3. Pinto A, Haberland CM, Baker S. Dent Clin North Am 58(20: (2014) 437-453.

4. Songu M, Adibelli H, Diniz G. (2012), White sponge nevus: Clinical suspicion and diagnosis. Pediatr Dermatology, 29(4): 495-497. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01414.x

5. Vucicevic-Boras V, Cekic-Arambasin A, Bosnjak A. White Sponge Nevus. Acta Stomat Croat: Case Report 2001;291-292.

NANCY W. BURKHART, BSDH, EdD, is an adjunct associate professor in the department of periodontics, Baylor College of Dentistry and the Texas A & M Health Science Center, Dallas. Dr. Burkhart is founder and cohost of the International Oral Lichen Planus Support Group (http://bcdwp.web.tamhsc.edu/iolpdallas/) and coauthor of General and Oral Pathology for the Dental Hygienist. She was a 2006 Crest/ADHA award winner. She is a 2012 Mentor of Distinction through Philips Oral Healthcare and PennWell Corp. Her website for seminars on mucosal diseases, oral cancer, and oral pathology topics is www.nancywburkhart.com. She can be contacted at [email protected].