Health Literacy

a life-threatening communication gap

by Jennie M. Fleming, RDH, BS, MEdAlmost one out of every two adults in America is affected by this problem. It has no deference for education, age, race, or income. It is a serious problem that costs the health-care system more than $58 billion a year and could result in a malpractice claim against any medical professional. According to the Institute of Medicine, 90 million people in the United States suffer from it, and it directly affects their ability to communicate with a health-care provider. It affects a person’s ability to access the services he or she needs. The problem is low health literacy, and more than 75 million Americans suffer from either basic and/or below basic health literacy skills. These patients are in your practice and you may not even know it (Figure 1).

Definitions of literacy

Health literacy is the degree to which an individual has the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.1 Low health literacy is the inability to read, understand, and act correctly on even basic health information and instructions.The 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy defines four levels of literacy: below basic, basic, intermediate, and proficient.

1) The below basic level describes only the most simple and concrete literacy skills, ranging from being nonliterate in English to having the ability to locate:

- Information in short, commonplace texts

- Information and following written instructions in simple documents (charts or forms)

- Numbers and being able to use them to perform simple, quantitative operations (basically addition)

2) The basic level refers to skills necessary to perform everyday simple literacy activities including:

- Reading and understanding short commonplace texts

- Reading and understanding simple documents

- Using easily identifiable quantitative information to solve simple, one-step problems when the arithmetic operation is specified or given

3) The intermediate level refers to the ability to perform moderately challenging activities and includes:

- Reading and understanding moderately dense, less commonplace texts and being able to summarize, make simple inferences, determine cause and effect, and identify the author’s purpose

- Locating and making simple inferences about information in dense, complex documents

- Locating less familiar quantitative information and being able to use it to solve problems when the arithmetic operation is not specified

4) The proficient level includes skills necessary to perform more complex and challenging activities such as:

- Reading long, complex, abstract texts and synthesizing the information in order to make complex inferences

- Integrating, synthesizing, and analyzing multiple pieces of information from complex documents

- Locating and using more abstract quantitative information to solve multistep problems including more complex arithmetic operations.2

Anyone can be affected

Anyone can be affected by low health literacy, regardless of gender, age, race, education, income, or ethnicity. Although the majority of people with marginal or low literacy are white native-born Americans,3 changing demographics suggest that low literacy is an increasing problem among certain racial and ethnic groups, non-English-speaking populations, and people over age 65. One study of Medicare enrollees found that 34 percent of English speakers and 54 percent of Spanish speakers had inadequate or marginal health literacy.4 Also affected are the chronically ill, whose literacy skills are their strongest link to their knowledge and understanding of their diseases. To be health literate, a person must be able to read, listen, understand, reason, and solve problems in order to make informed choices regarding their health and health care. Health literacy is vital to positive health and treatment outcomes, as well as to patient care.

Effects of low health literacy

Low health literacy separates patients from the health-care system. Research has suggested that with low health literacy, a person is more likely to make medication errors and less able to follow prescribed treatment and/or adhere to self-care regimens. Of patients on medications, only half are taking their medications as directed.

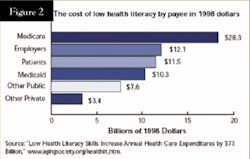

Other findings suggest that having low health literacy makes it more difficult to negotiate the health-care system. Lacking the needed skills, patients with low literacy may fail to seek preventive care. Not only do they have more than double the risk for hospitalization, they also tend to remain hospitalized nearly two days longer than those with higher literacy skills (Healthy People 2010). The average annual health-care costs of persons with very low literacy (reading at the grade-two level or below) may be four times greater than for the general population5 (Figure 2).

It is estimated that 75 percent of persons in the United States with chronic physical or mental health problems are in the limited literacy category.6 People with low reading skills who have chronic conditions, such as asthma, hypertension, and diabetes, have been found to have less knowledge of their conditions than people with higher reading skills.7 Unfortunately, most health materials are written at the 10th grade level or above and in the United States, almost half of adults read at an eighth grade level or below.8

As the baby-boomer generation matures, low health literacy among the elderly will be a potentially large problem. With age, the ability to read appears to decline. Currently, almost half of the elderly population has low reading skills. A study performed in a public hospital of patients age 60 and older found that 81 percent could not read basic appointment materials, understand simple written instructions, or read their prescription labels.9 Considering age, income, employment status, education level, literacy skills, racial or ethnic background, literacy skills are the strongest predictor of an individual’s health status.10

In 1995, a study performed in two public hospitals found that of 2,659 low-income patients interviewed, 26 percent could not read their appointment card. Nearly 50 percent couldn’t tell if they qualified for free care after reading information provided by the hospital. Of English-speaking patients, 33 percent could not read basic health materials, 42 percent did not know what “taking medication on an empty stomach” meant, and 60 percent could not understand an informed-consent document9 (Figure 3).

Determinants of good health literacy

A health literate person can recognize a need for health information and identify possible sources of information. The health literate individual can search information sources and find relevant information, evaluate that information for quality, and use it to help make healthy decisions.11

Trends and challenges

The importance of health literacy in America is apparent in a number of trends. These trends affect the rise of health-care costs, managed-care insurance plans, treatment changes, the population as it ages, and the diversity of people living in the United States. The association has been made between low health literacy and increased costs. Managed-care programs and insurance plans expect patients to take charge of their health. Patients with low health literacy have difficulties understanding the system and accessing care. Medical treatments are becoming more complex as advancements are made. To the health illiterate, challenges include the inability to prevent medical errors in making informed consent and in following care and medication instructions. Challenges to the decreasing health literacy among the aging population include the inability to understand and act on the information given. Increasing diversities in America promote communication barriers that include cultural beliefs, as well as linguistics.12

Improving health literacy

State policy-makers are beginning to address the health literacy problem with initiatives to create task forces to study the problem and develop recommendations for improvements. States included are Louisiana, Georgia, Virginia, Alaska, California, Massachusetts, and Alabama. Some of the initiatives promote the use of plain language, and provide resources to health-care providers, etc., that would help improve access to care among specific populations. Others are promoting pilot projects to teach adult learners language skills using health information. One is providing “Healthy Reading Kits” for grades two through eight which include health-related reading materials and manuals to help teachers tie content to the state’s reading standard.12

Health-care providers can help by simplifying health materials:

- Use clear and plain language.

- Write patient materials at a sixth-grade reading level or below.

- Use graphics, white space, and larger font sizes.

- Translate information, if possible, into the individual’s language.

- Verbally review the information with the patient.

- Ask the patient to repeat the information and ask pertinent questions regarding the information to help assure understanding. Encourage your patient to ask:

- What is my main problem or chief complaint?

- What should I do and how should it be done?

- Why is it necessary to do this?10

- Promote community understanding by incorporating health education and materials for classrooms including levels K through12 and also for adult literacy classes.12

Summary

In today’s medically complex society, a person must have the skills to access care and navigate the system. Consumers must be able to take charge of their health care and be able to make life-challenging decisions. They must be able to make decisions regarding health information, disease prevention, treatments, insurance plans, managed-care programs, health-care providers, types of services available and facilities which provide these services, prescription information, alternative medicine options, and even basic home-care instructions. A person’s life may well depend on his or her ability to follow instructions, especially if he or she doesn’t understand the instructions. As health-care providers, we must never just assume our patients understand what we are talking about and what we are doing. We must not assume they can read and understand written materials we provide, whether these materials are prescriptions, brochures, or referrals. In doing so, we lean toward negligence, and negligence is malpractice.

References

1 HHS, NIH, National Library of Medicine. Selden CR, Zorn M, Ratzan S, et al. eds. Health Literacy, Jan. 1990 through Oct. 1999. NLM Pub. No. CBM 2000-1. Bethesda, Md. NLM, 2000, vi.

2 Kutner M, Greenberg E, Jin Y, Paulsen C. (2006). The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results From the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NCES 2006-483). U.S. Department of Education. Washington, D.C. National Center for Education Statistics.

3 Kirsch I, Jungeblut A, Jenkins L, et al. Adult Literacy in America: A First Look at the Findings of the National Adult Literacy Survey. Washington, D.C. National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education, 1993.

4 Gazmararian JA, Baker DW, Williams MV, et al. Health literacy among Medicare enrollees in a managed-care organization. Journal of the American Medical Association 1999; 281:545-551.

5 Weiss BD, Blanchard JS, McGee DL, et al. Illiteracy among Medicaid recipients and its relationship to health-care costs. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Under-served 1994; 5:99-111.

6 Davis TC, Meldrum H, Tippy PKP, et al. How poor literacy leads to poor health care. Patient Care 1996; 94-108.

7 Williams MV, Baker DW, Parker RM, et al. Relationship of functional health literacy to patients’ knowledge of their chronic disease. A study of patients with hypertension and diabetes. Archives of Internal Medicine 1998; 158:166-172.

8 Reading Between the Lines - An MLA Satellite Teleconference Program; CASAS: http://www.casas.org/lit/litcode/Search.cfm.

9 Williams M, Parker R, Baker D, et al. Inadequate functional health literacy among patients at two public hospitals. JAMA 1995; v274n21:1677-1682.

10 Partnership for Clear Health Communication, c/o Fleishman-Hillard, 2 Alhambra Plaza, Suite 700, Coral Gables, FL 33134. http://www.askme3.org/.

11 Medical Library Association http://www.mlanet.org/resources/healthlit/define.html.

12 Health Literacy Tool Kit, A Comprehensive Resource for Policy-Makers - The Council of State Governments: www.csg.org.

Jennie Fleming, RDH, BS, MEd, is the dental prevention coordinator for the East Metro Health District in Lawrenceville, Ga., and an adjunct public health instructor at Georgia Perimeter College in Dunwoody, Ga. She can be contacted by e-mail at [email protected].

null