Diabetes: Anyone, anytime

by Frances Dean Wolfe

While age, family history, obesity, and a "couch potato" lifestyle are the most common contributing factors of type 2 diabetes, the disease may hit anyone, even where there is no family history. As most often the first clinical contact with new patients, the first team member to observe the oral manifestations associated with diabetes.

On Monday morning a 14-year-old girl presents with general malaise and oral candidiasis. Her parents report she has felt this way all weekend and that she has lost seven pounds - inexplicably - during that time. There was no family history of diabetes.

A teenage boy claims to feel weak and ill. His parents take him to the family physician who attributes his symptoms to growing pains and a touch of the flu. Later that week he collapses on the pitcher’s mound at a baseball game. The paramedics cannot revive him. They call a medevac helicopter and tell his parents to meet them at the hospital, where there will be a 50-50 chance they will find him alive. An emergency room nurse asks if there is a family history of diabetes, to which the parents respond no. Soon afterward the parents learn their son’s blood sugars are in the 600s! He is, indeed, lucky to be alive!

A 55-year-old obese woman with a sedentary lifestyle complains of blurred vision, lack of taste, frequent urination, fatigue, and an insatiable thirst. In fact, she carries a water bottle with her throughout the day. Her 24-hour urine collection analysis reveals no kidney damage; however, her fasting bloodwork reveals her glucose level at 167; her long-term A1C is 7.1.

In each of these cases, the patient was diagnosed with diabetes. The sad fact is that diabetes is occurring in epic proportions from a generation ago. And while age, obesity, family history, and a “couch potato” lifestyle are the most common contributing factors, diabetes may hit anyone, even where there is no family history.

Because the hygienist is often the first clinical contact with new patients, it behooves him or her to be vigilant to the oral signs and symptoms of diabetes. This is to alert the dentist, who, upon further examination, may refer the patient to his or her physician for follow-up assessment.

Just what exactly is diabetes?

Diabetes mellitus is a syndrome of abnormal carbohydrate, protein, and fat metabolism. It results in acute and chronic complications due either to the lack of insulin or to insulin resistance. There are three types of diabetes:

• Type 1 diabetes - (frequently referred to as juvenile diabetes) results from an absolute insulin deficiency. Symptoms include the classic “P” triad: polyphagia (excessive hunger), polydipsia (excessive thirst), and polyuria (excessive secretion of urine); also weight loss, irritability, drowsiness, and fatigue.

• Type 2 diabetes - (often referred to as adult onset diabetes) is the result of insulin resistance and/or an insulin secretory defect. Symptoms develop more slowly and frequently without the classic triad; instead, these patients may be obese and may have pruritis (excessive itching of the skin), peripheral neuropathy (nervous system disturbances, including loss of feeling in the extremities), and/or blurred vision. They may also suffer from opportunistic infections, including oral and vaginal candidiasis, as well as frequent bladder infections and foot infections.

Those with long-standing diabetes may develop microvascular and macrovascular conditions that may lead to irreversible damage to the eyes (retinopathy and cataracts), kidneys (nephropathy), nervous system (neuropathy and paresthesias), and heart (accelerated atherosclerosis), as well as recurrent infections and impaired wound healing. It is the most common form of diabetes.

• Gestational diabetes - (frequently referred to as pregnancy diabetes) is a condition of abnormal glucose tolerance during pregnancy. It usually resolves postpartum. Women diagnosed with gestational pregnancy are at higher risk for developing type 2 diabetes later in life.

How prevalent is diabetes?

A recent report from the National Centers for Health Statistics cited more than 10 million Americans were living with diabetes; 124 million worldwide. Unfortunately, patients with diabetes have a substantially higher risk of mortality and shorter life expectancy. In fact, diabetes and its complications was the sixth most common cause of death in 2001, accounting for more than 72,000 deaths in the United States.

Diabetes also has a higher prevalence in certain minority groups, including African-Americans, Hispanic-Latinos, Asian-Americans, Native Americans, and those of Pacific Island descent.

During the past 20 years, the prevalence of diabetes has increased 30 to 40 percent. Obesity is a major risk factor in the development of diabetes at any age. Alarmingly, about one-third of adults with diabetes in this country are currently undiagnosed.

Diabetes is no longer an older adult disease. With increased obesity in children comes an increased risk for diabetes. The American Diabetes Association estimates one out of every six overweight children has prediabetes, a strong precursor and risk factor for type 2 diabetes. In fact, in one study, one-third of new cases of type 2 diabetes were detected in 10- to 19-year-olds! Further, two million U.S. “tweens” and teens (12 to 19 years) have prediabetes.

Compared to 20 years ago, the rate of overweight children has doubled for kids ages 6 to 11 and has tripled for those between the ages of 12 and 19. Overweight tweens and teens have a 70 percent chance of becoming overweight/obese adults; the risk increases to 80 percent if one or both parents are overweight or obese.

What can the hygienist do to help young patients with prediabetes/diabetes? Most effective techniques include empowering the adolescent to take action to achieve self-management. This includes motivating the patient to engage in age- and interest-appropriate physical exercise. Kids also seem to find electronic gadgets more interesting. And when they are more interested, they are more likely to follow through with good home care. They seem to like power toothbrushes, colorful water jets, and toothbrushes that light up. And when they like the technology, they are more likely to use it. WaterPikTM, Inc. conducted tests on diabetic adults and found reduced systemic inflammatory markers and inflammation associated with periodontal disease in those who used these home irrigation devices.

All members of the dental team can play an important role in the diagnosis and management of their diabetic patients. The dental hygienist can take the opportunity to counsel diabetic patients on how to improve glucose regulation, maintain oral hygiene at home, and improve nutrition.

The most common risk factors for type 2 diabetes

Because type 2 diabetes is the most common, it is important for the hygienist to be aware of its risk factors, which include:

- Being overweight/obese

- Being physically inactive (living the “couch potato” lifestyle)

- Having an immediate blood relative with diabetes, including a parent or sibling

- Being of African-American, Asian-American, Hispanic-Latino, Native American, or Pacific Island descent

- Having had a baby who weighed more than nine pounds at birth or having had gestational diabetes

- Having uncontrolled hypertension (over 140/90)

- Having low (HDL) levels of good cholesterol (35 mg/dl or lower)

- Having high triglyceride (blood fat) levels (250 mg/dl or higher)

- Having higher than normal blood glucose levels (also called impaired fasting glucose, impaired glucose tolerance, or prediabetes)

- Having polycystic ovary disease

- Exhibiting signs or symptoms of insulin resistance, including a skin condition called acanthosis nigrans (characterized by dark patches of skin on the neck or other areas of the body)

- Having a history of blood vessel disease

Common symptoms of diabetes

Many diabetic patients have no symptoms, which is why so many go undiagnosed for so long. One can actually have type 2 diabetes for up to 10 years prior to diagnosis. The concern is that it can harm the body before it is diagnosed. Due to the growing incidence of the disease, many health-care experts currently recommend a fasting blood glucose test to check for diabetes in patients 45 years and older, especially if overweight or obese, or who have a family history.

Common symptoms of diabetes or elevated blood glucose include:

- Frequent urination

- Extreme thirst

- Extreme hunger

- Blurred vision

- Frequent infections

- Delayed healing

- Itchy skin (with no other medical explanation)

- Unexplained sudden weight loss

- Loss of taste

- Fatigue

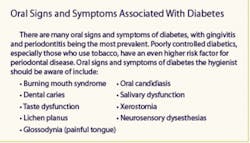

Oral manifestations of diabetes

Hygienists, as well as all members of the dental team, should be familiar with oral manifestations of diabetic patients. This is because vigilance in changes in the oral cavity at recall appointments may be an indicator of the emergence or progression of the disease. If this is the case, the dentist should refer the patient to his or her physician for appropriate testing, assessment, and management.

• Gingivitis and periodontitis - Persistent poor glycemic control has been reported with the incidence and progression of diabetes-related oral complications, which include gingivitis, periodontitis, and alveolar bone loss. Periodontal disease is the most prevalent oral complication in both insulin-dependent (IDDM) and noninsulin-dependent (NIDDM) patients and has been named the “sixth complication of diabetes mellitus.”

Periodontal disease is more severe and occurs with higher frequency in both NIDDM and IDDM patients, especially if the diabetes is not well controlled and there are other complications, such as retinopathy. The reason for greater incidence of periodontal destruction in diabetic patients in unclear. However, studies of the periodontal flora find similar microorganisms in diabetic and nondiabetic patients, suggesting that alteration in host responses to periodontal pathogens account for these differences in periodontal destruction. Current research supports the conclusion that periodontal infections contribute to problems with blood sugar control, so treatment of chronic periodontal infections is imperative in managing diabetic patients.

• Dental caries - Because diabetic patients are susceptible to oral sensory, periodontal, and salivary disorders, any or all of these conditions could increase their risk of developing new or recurrent caries. Factors in caries development include traditional elements (Streptococcus mutans and previous caries), as well as poor metabolic control of the diabetes.

Caries in the crowns of teeth appear to be greater in adults with poor control of IDDM. However, the prevalence of root caries requires further studies. Oral infections aside from dental caries and periodontal disease are more severe. Life-threatening deep neck infections and palatal ulcers are examples of the severity of these conditions.

• Oral mucosal diseases - Diabetic patients experience higher prevalences of lichen planus, recurrent aphthous stomatitis, and oral fungal and bacterial infections. These most often may be caused by chronic immunosuppression and require continued followup.

• Salivary dysfunction - Diabetic patients, especially those with type 2, often complain of dry mouth or xerostomia and experience salivary gland dysfunction. The complaint of “thirst” is very common. The hygienist may recommend over-the-counter salivary substitutes to help diabetic patients feel more comfortable.

• Candidiasis - Is a common fungal infection of the oral mucosal surfaces and removable prostheses and often presents in adult diabetics. Candida pseudohyphae, a cardinal sign of oral candida infections, have been reported significantly higher in diabetics who smoke cigarettes, those who wear dentures, and who have poor blood sugar control. Salivary hypofunction may also increase candida infections.

• Burning mouth and taste disturbances - Diabetic patients have increased complaints about burning mouth. More than one-third of adult diabetics report hypogeusia (abnormal diminished taste perception). In some cases this may result in overeating, leading to obesity; in others, loss of weight due to lack of appetite. Many diabetic patients may also exhibit the characteristic “fruity breath.”

Dental treatment considerations for diabetics

Because many diabetics are at risk of developing oral complications, many require antibiotic coverage. Because diabetics may experience delayed wound healing and a higher susceptibility to infection, cultures should be performed for acute oral infections with appropriate antibiotic therapy initiated. Those who undergo oral surgical procedures may experience delayed healing and/or alveolitis (dry socket). Ouch!

Some diabetic patients may require an adjustment of insulin because dental alveolar surgery, orofacial infections, and the stress of anticipated dental procedures can thus increase serum glucose levels; this increases metabolic insulin required for diabetic patients. Thus, the dentist may consult with the insulin-dependent patient’s physician prior to proceeding with surgical or involved restorative procedures. Patients who require insulin usually require a slight increase in insulin due to an acute oral infection or just prior to undergoing dental treatment.

Adjunct treatment considerations for diabetic patients

Medications administered for dental procedures may require adjustment of diabetes-associated therapies. For instance, large amounts of epinephrine may antagonize the effects of insulin and result in hyperglycemia. Small amounts of systemic corticosteroids can severely worsen glycemic control. Alternatively, hypoglycemia can be promoted by aspirin, sulfa antibiotics, or antidepressants.

Every dental office should be equipped with an emergency kit containing an immediate source of glucose in the event of a diabetic-induced hypoglycemic reaction. Pharmacists can recommend ready sources of instant glucose. CakeMateTM smeared on the gingiva or administration of one-half cup of orange juice is usually sufficient.

Recommended management strategies for diabetics

Not all diabetic patients require insulin. The determining factor depends upon the pancreas’s ability to manufacture sufficient insulin on its own. If so, oral or injected insulin is not required. It is required, however, for patients diagnosed with type 1 diabetes and for those with type 2 diabetes who do not respond to dietary and exercise therapy alone. Diet and physical exercise, along with weight control, are all necessary components of diabetes management.

Overall, there are three effective management strategies the hygienist can instill to help diabetic patients manage their disease:

- Planned meals, choosing what, how much, and when to eat (to maintain recommended glucose levels).

- Being physically active (exercise actually lowers blood sugar) on a regular basis.

- Taking prescribed medications (if needed).

In meeting these three self-management strategies the anticipated outcomes for the patient are normalized blood glucose levels; prevention of acute complications and elimination of symptoms of the disease; maintenance of ideal body weight; and prevention or minimization of chronic complications.

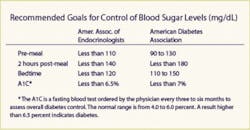

Home glucose monitoring helps diabetics regulate rapid fluxes in blood sugar levels contingent upon diet, medications, and physical and psychological stresses. Daily recording of premeal and (two hours) postmeal glucose levels helps the diabetic learn to adjust dietary intake, especially high-starch carbohydrates, as well as overall caloric intake. Diabetic patients should undergo routine examinations by physicians to monitor triglycerides, blood pressure, urine protein, and fasting and long-term glucose levels.

The hygienist, as well as all members of the dental team, should be aware of treatment needs and concerns of oral manifestations of diabetic patients. In some cases, patients are unaware of their diabetes, and a visit to the dental office may alert the dentist to refer a suspected undiagnosed diabetic to his or her physician for assessment. Because diabetes is on the rise, both in adolescents and in adults, dental offices are more likely to treat an increasing number of diabetic patients in the future.

Today, all three patients are doing well. The young girl has had an insulin pump implanted. She is enrolled in her freshman year of college and is an active athlete. She tests her glucose levels 10 times daily.

The teenager is currently enrolled in law school. He plans to earn his doctorate and become a law professor. He tests his glucose 10 times daily and takes oral insulin daily.

The “couch potato” middle-aged lady said, “This was the wake-up call of a lifetime.” She brought down her weight, glucose levels, and blood pressure through diet and exercise, alone. She realizes someday she may need to be on medication; however, she credits her primary care provider and nutrition counselor for early interception and for putting her on the right track. Today she is looking forward to retirement and traveling with her husband; she enjoys playing with her first grandchild.

References

• Al-Mubarak S, Ciancio S, Aljada A, et al. Comparative evaluation of adjunctive oral irrigation in diabetics. J Clin Periodontal 2002; 29(4)295-300.

• American Diabetes Association: 1-800-DIABETES (342-2383). www.diabetes.org.

• Dietz E. Oral manifestations of diabetes. Dental Home Study Program. NADA: Falls Church, Va. 2006.

• Hedley AA, Ogden CL, Johnson CL, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among U.S. children, adolescents, and adults. 1999-2002. JAMA 2004; 291(23):2847-2850.

• Jahn C. Obesity and diabetes: implications for children and adolescents. JAG, June 2006.

• Loe D, Genco R. Oral complications in diabetes.

• Loe H. Periodontal disease. The sixth complication of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 1993; 16:329-34.

• Long, et al. Oral manifestations of systemic diseases. MS Journal Oct.-Nov. 1998; Vol. 65, No 5 & 6.

• Oliver RC, et al: Diabetes - a risk factor for periodontitis? Northwest Dent 1991; 70:26-27.

• Overweight and Obesity: Health Consequences. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. www.surgeongeneral.gov. Accessed 03-31-06.

• Rosenbloom AL, Joe RH, Young RS, Winter WE. Emerging epidemic of type 2 diabetes in youth. Diabetes Care 1999; 22(3)345-354.

• Rozeli M, et al. Oral manifestations of diabetes mellitus in controlled and uncontrolled patients. Braz Dent J 1995; 6(2):131-136.

• Ship JA. Diabetes and oral health: an overview. JADA Oct. 2003; Vol. 134.

• Williams DE, Cadwell BS, Cheng YJ, et al. Prevalence of impaired fasting glucose and its relationship with cardiovascular disease risk factors in U.S. adolescents. 199-200. Pediatrics 2005; 116(5):1122-1126.