Systemic diabetes

Oral implications for elderly patients

by Marcy Ortiz, RDH, BA

The elderly population has grown immensely over the last century and will continue to grow in the near future. In the early 1900s, those over 65 years old were a very small percentage of the overall population at only 4% (Spencer and Tsokris, 2005). This is not true today. When the baby boomer generation reaches its senior years, they will comprise "19-20% of the total United States population" (Spencer and Tsokris, 2005, p.1), a significant increase compared to the mere 4% a century ago. The implications of delivering oral health care to such a large elderly population requires consideration as their oral health can impact their overall health.

Most elderly see their primary care physician on a regular basis, but visits to their dentists are usually more frequent. Statistics show that in 2002, "64% of those over age 65 had a dental visit in the past year and 73% had a prophylaxis;" only "25% of this population is completely edentulous" (Spencer and Tsokris, 2005, p.1). Increasingly, our elderly are keeping their teeth longer with 75% having their natural teeth and with health improving into older age.

Dental concerns in caring for the elderly involve more than the status quo of offering "just a cleaning" or treating decayed teeth. Seniors are presenting with chronic illnesses such as diabetes, high blood pressure, arthritis, heart disease, autoimmune disease, asthma, etc., and these co-morbidities influence their health. With a large percentage (80%) of seniors having at least one chronic condition, and 50% at least two chronic conditions, clearly these systemic illnesses take a toll on seniors' health, becoming a factor for their oral health too (Spencer and Tsokris, 2005, p.1).

Diabetes is one major chronic systemic disease contributing to periodontal breakdown requiring treatment in the elderly population. It is a disease exhibiting a clear bidirectional relationship with periodontal disease. This unique relationship and the resulting oral effects makes treating the periodontal-diabetic elderly patient especially important for the hygienist to address as our dental population ages.

The prevalence of diabetes worldwide is estimated at 221 million. In certain regions worldwide (Africa, Asia), it "could rise twofold or threefold. People with diabetes have a substantially higher risk of mortality and shorter life expectancy" (Ship, 2003, p. 4S) compared to those without the disease.

In the United States, 2007 statistics indicate "23.6 million people or 7.8% of the population" have diabetes (diagnosed 17.9 million and undiagnosed 5.7 million) and is the "seventh leading cause of death" (CDC, 2007, pp. 5, 8). Diabetes has unequal racial discrepancies with Hispanics two times the rate of Caucasians, and Blacks experience an even higher risk and had greater complications with their diabetes (Ship, 2003, p. 5S) Black risk is 19% compared to Caucasian 8.7%.

Let's review the two major types of diabetes. Type 1 diabetes can occur at any age, but is usually associated with an early childhood diagnosis. Type 2, called adult onset diabetes, is the most prevalent form of diabetes "account[ing] for 90-95% of all diabetes cases" (Kaplan-Mayer, 2010, p. 14). It occurs primarily in adults beginning with insulin resistance whereby the cells are not using insulin properly, and evolves to pancreatic malfunction; the pancreas is not able to produce the insulin necessary for normal function. Adult Type 2 diabetes is "associated with older age, obesity, family history of diabetes, history of gestational diabetes, impaired glucose metabolism, physical inactivity and race/ethnicity" (CDC, 2007, p. 1).

Other types of diabetes exist (see Figure 1), but Type 2 is the predominant diabetes found in the elderly population, even though many new Type 2 diagnoses are in children due to obesity. Nonetheless, both diabetes types are areas of concern due to their chronic systemic conditions relating to dental disease, especially periodontal disease.

Pathogenesis of diabetes

The oral complications seen in diabetic patients are a result of exaggerated host response to their local microbial factors (Ryan et al., 2003, p. 35S) initiating vascular changes, the same as periodontal disease. These vascular changes seen in diabetics' tissues and organs occur in the gingival tissues too; all involve the same inflammatory mediators/markers. Diabetes, periodontal disease, and other conditions including "atherosclerosis, asthma, preeclampsia, neurodegenerative diseases…are all characterized by increased serum C-reactive protein (CRP), [cytokines]: tumor necrosis factor-a (TNF-a), interleukin-1b (IL1B), -6 (IL-6), and metalloproteinases," protein enzymes (Slim and Lavelle, 2009, p. 62). The results of these vascular changes from the inflammatory markers are what increases the severity of periodontal disease and decreases wound healing as these mediators are found in the gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) of patients with poorly controlled diabetes (Ryan et al., 2003, p. 37S).

Other altered metabolic changes in diabetes are collagen metabolism and PMN dysfunction. "These defects may predispose people with diabetes to periodontal disease" (Ryan et al., 2003, p. 38S) since "the profile of phagocytes" in diabetic patients is nearly the same as what we see in patients who suffer from aggressive periodontitis (Suzuki et al., 2007, p. 4). Collagen dysfunction has an effect on connective tissue resulting in impaired ability for healing, where PMN dysfunction predisposes those with diabetes to periodontal disease by poor chemotaxis via neutrophils and phagocytosis, ultimately playing a role in glycemic stabilization difficulties for diabetics.

Numerous individual factors may set the disease process in motion. Most likely, it is a culmination of many factors working together that increases the susceptibility of diabetics to periodontal disease.

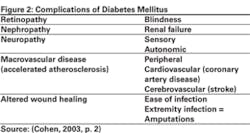

Diabetes has serious complications. It can increase susceptibility to healing, infection, hyperglycemia (increased blood sugar), and a variety of host metabolic complications: retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, macrovascular disease, and altered wound healing (Cohen, 2003, p. 2) (see Figure 2).

Retinopathy is a diabetic complication that leads the diabetic patient to impaired visual acuity and, for some, eventual blindness. For new cases of blindness among adults, diabetic retinopathy is the leading cause. Nephropathy involves the kidneys; its complications can include kidney dysfunction or failure. "Diabetes is the leading cause of kidney failure, accounting for 44% of new cases in 2005" (CDC, 2007, p. 10). Patients with serious nephropathy may be enduring end-stage kidney failure requiring dialysis or be on the organ donor list for kidney transplantation.

Neuropathy is a complication of the body's nervous system. It can occur anywhere in the body, even including the major organs. Dental manifestations will take the form of oral nerve concerns that cause burning of tissue and tongue (glossitis) and numbness in the extremities, such as hand numbness, affecting the patient's fine motor skills required to brush properly. More serious neuropathy can be a form of "diabetic nerve disease" and when coupled with poor wound healing, it is "a major contributing cause of lower-extremity amputations" (CDC, 2007, p. 10).

Macrovascular disease involves heart disease, high blood pressure, stroke, and atherosclerosis. The prevalence of diabetics to have cardiovascular complications is high; however, it is important to note the extent of the relationship. In 2004, 68% of diabetics age 65 and older listed heart disease on their death certificate, and in the same year stroke was noted 16% of the time. Stroke risk for diabetic individuals is two to four times greater than found among nondiabetic individuals (CDC, 2007, p. 10). Diabetics are prone to many systemic issues, and cardiovascular disease is one such systemic complication.

These are serious systemic complications. In addition, periodontal disease has been referred to as the "sixth complication of diabetes" in several diabetes/periodontal disease studies (Ryan et al., 2003, p. 35S) (Kandelman, Petersen and Ueda, 2008, p. 228). Patients with Type 2 diabetes are "three times more likely to develop periodontal disease" and smokers who have diabetes are "20 times more likely to develop periodontitis" with loss of attachment and bone loss compared to adults who do not have diabetes (Vernillo, 2003, p.26S).

One particularly startling study associating the devastating effects of diabetics and periodontal disease is a study following the Pima Indians of Gila River Indian community in Arizona. "We've been studying the Pima Indians for the last 25 years" with the median time frame of 13 years (Genco, 2008, p. 18). They are a collective group with extremely high incidence of diabetes. Ryan et al. (2003), in referring to this study, states the Pima Indians have the highest incidence of diabetes in the world since 50% of its population older than 35 years have Type 2 diabetes. They exhibit periodontal bone loss at early ages which increases as they age; "the loss of teeth was ... 15 times high[er] in Pima Indians with diabetes than in Pima Indians without the disease" (Vernillo, 2003, p. 26S).

This is a significant statistic showing the relationship and association linking diabetes and periodontal disease. There was also an unexpected disease relationship outcome noted in this study. The Pima Indians who had diabetes and periodontal disease had "two times greater risk of dying of heart disease ... four times greater risk of dying from kidney disease [and] ... a fivefold greater chance of having albuminuria [albumin in urine, indication of kidney disease] than those with diabetes who do not have periodontal disease" (Genco, 2008, p. 18).

The renal disease is remarkable because it follows the inflammatory process that periodontal disease follows. Both have the same basic "pathophysiologic process as in heart disease" including specific inflammatory factors in the bloodstream resulting in vascular damage (Genco, 2008, p. 18). For example, if the vascular damage is in the heart, this leads to heart disease; if it is in the kidneys, it leads to kidney disease; and if it is in the gingival connective tissues, it leads to pathogenesis in the periodontium, resulting in periodontal disease.

Oral complications for diabetics

The problem for diabetics is the bidirectional relationship to periodontal disease. If their glycemic control is poor, the uncontrolled diabetes increases the risk for greater periodontal severity, and if their periodontal disease is not treated or stabilized, it in turn affects their glycemic blood level negatively. This is why the diabetic patient has difficulty achieving a balance in keeping both their diabetes and periodontal disease stable.

Diabetics who are diligent and keeping their glycemic levels normal are not necessarily at a higher risk for periodontal disease. It is all about keeping the blood sugars stable. To do this, diabetic patients need to regularly get their hemoglobin A1C (HbA1c) level checked, to see how their glycemic levels are averaging, enabling them to make necessary modifications. The HbA1c "provides an average blood glucose level over the previous two or three months as an indication of long-term glycemic control" (Boyd, 2008, p. 41).

The proper level for a controlled diabetic glycemic level is at or below 7%. "Lowering A1C to below or around 7% has shown to reduce microvascular and neuropathic complications of Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes ... for microvascular disease prevention, the A1C goal for adults is <7%" (ADA Diabetes Care, 2009, p. S3); ideally, 6.5% or less is preferred. A1C testing should be done twice a year in patients with stable glycemic levels and quarterly in patients with poor glycemic levels (Boyd, 2008, p. 42). Surprisingly, if a newly diagnosed diabetic patient can keep their A1C target level below 7% during their first few years in managing their disease, their long-term microvascular complications are greatly reduced.

A1C level indicates stability of the diabetic patient. If a patient's A1C glycemic level is only fair to good, they are at increased risk for severe periodontal disease – approximately 50% to 200% higher than patients who do not have diabetes (Ryan et al., 2003, p. 36S). Communicating this to the dental diabetic patient can encourage them to work diligently to keep their A1C levels stable and reduce their susceptibility to a poor periodontal outcome.

Oral complications are pervasive with diabetic patients (see Figure 3), and those having difficulty controlling their glycemic blood sugar have a host of dental problems. In addition, for undiagnosed diabetics, they do not know they have a blood sugar problem, yet may still exhibit oral symptoms relating to their disease. Regardless of why their diabetes is uncontrolled or undiagnosed, the oral effects are devastating and can include "gingivitis, periodontal disease, xerostomia, and salivary gland dysfunction; increased susceptibility to bacterial, viral and fungal (oral candidiasis) infections; caries; periapical abscesses; loss of teeth ... taste impairment; lichen planus; and burning mouth syndrome" (Vernillo, 2003, p. 25S).

The most common oral complication is periodontal disease and becomes a great risk factor for diabetics exhibiting poor glycemic control. Another probable complicating factor is the age of diagnosis. There is evidence associating the years a person has the disease with increased progression of their periodontal disease – a sort of dose response that, with age, increases a diabetic's susceptibility to accelerated periodontal problems. Thus, when treating the elderly diabetic, this will be a significant systemic concern for dental hygienists.

Diabetic dental concerns/treatment

Diabetic patients will be under the care of an internist or endocrinologist, and their protocol will vary depending on their particular diagnosis and severity. Prediabetic patients have elevated glucose blood levels but not to the level requiring a true diagnosis of diabetes. This patient may say they have "borderline diabetes." They are typically not treated by medication; more likely, their physician recommends altering their diet and lifestyle, hoping to keep glucose levels stable or improving.

Adult Type 1 diabetics are using insulin by injection or an insulin pump. Type 2 diabetics can have a varied treatment protocol. They can be on oral medication only or a combination of oral medication, insulin injection or pump. However, the majority of diabetic patients will be on oral medication (see Figure 4).

Diabetic patients, whether on medication or insulin, need to inform their hygienist with this information. Otherwise, the hygienist needs to ask specifically what the patient is taking for their diabetes. If a Type 1 diabetic, what kind of insulin are they administering, how often, and when was their last dose? If a Type 2 diabetic, note what medication they are taking, frequency, and note the dosage in the chart. This is critical information that will prove invaluable in the event of a medical emergency.

Additionally, before the patient is to receive oral care, the most important piece of information to ask from a diabetic patient is their recent A1C level. If the patient does not know it, then the hygienist or staff should call the physician. This is the best indicator of how stable their diabetes is and thus the risk and positive outcomes regarding their dental treatment. If their diabetes is not stable and their periodontal condition is declining, immediate action must be taken to prevent further systemic complications.

Collaboration with the patient's internist or endocrinologist is beneficial for all parties concerned due to their bidirectional disease risk; their physician will be aware of possible declining periodontal health and associated complications, and the hygienist/dentist will be aware of the patient's glycemic level of control.

When the patient is in the office receiving care, the primary concern is to avoid a hypoglycemic medical emergency. There are a few simple recommendations to help in this regard.

First, schedule the dental appointment in the morning as the risk for hypoglycemia is greater in the afternoon. If an afternoon appointment cannot be avoided, and a hypoglycemic event occurs, it can be effectively managed. However, recognizing the symptoms is critical so glucose can be administered promptly. A patient's hypoglycemic signs can vary but may include "dizziness, perspiration, confusion, shakiness, and irritability" (Boyd, 2008, p. 41).

A patient exhibiting hypoglycemic signs will know when their symptoms begin or when they are experiencing a hypoglycemic event and will notify their hygienist or dentist immediately. The protocol for the hygienist is the order of procedure. Never leave the patient. Have a co-worker call 911 and then they can assist you by getting the patient their first dose of carbohydrate by following the "Rule of 15":

- Step 1 – Eat or drink 15 grams of glucose or fast-acting carbohydrate (an example would be granulated sugar on tongue or) 1/2 cup of orange juice

- Step 2 – Wait 15 minutes

- Step 3 – Check blood glucose with a glucose monitor. If the blood glucose is low (<70mg/dl), repeat steps 1 through 3 (Boyd, 2008, pp. 41-2).

Many offices prepare for a hypoglycemic event by keeping a sugar packet in a nearby drawer for implementing treatment within seconds as a delay in response can result in a greater medical emergency. Also, do not give the patient too much glucose or carbohydrate - more is not better. Too much can make their blood sugar even more irregular and difficult to stabilize.

Please note that a glucose monitoring device in the dental office requires specific training, a certificate, and biannual fee. If the dental office does not want to invest in this training (or liability), call 911 immediately and follow the "Rule of 15," and the EMS can further stabilize the patient upon arrival.

Other complications in poorly controlled diabetes that require specific attention are retinopathy or neuropathy. The hygienist needs to confirm if the patient is experiencing any of these complications. If the patient is experiencing retinopathy, they will have some form of visual impairment, and in the case of neuropathy, possible numbness or tingling in their hands or fingertips.

Both of these complications will require the hygienist to alter their patient's self-care instructions to help them adapt to effective cleaning while overcoming these obstacles. For example, an electric toothbrush may be easier for them to use for visual impairment and more effective as well to use for their numb hands as it requires less brushing time for effectiveness. Visually, the patient will need more feedback on oral home care recommendations and areas they need to concentrate on to remove debris, as these areas won't be apparent to them due to their visual impairment.

Supportive periodontal therapy will be the area in which dental hygienists can have the greatest impact for their patients' oral health. Once their disease is classified and their needs determined, active treatment and subsequent follow-up care can be accomplished. This preventive care is usually carried out by a dental hygienist, as the treatment protocol for diabetic patients is normally nonsurgical in nature. A nonsurgical approach, scaling and root planing, is recommended to reduce the risk of systemic complications and delayed healing seen in surgical treatment.

Adjunct therapy should also be considered for the diabetic patient, such as Arestin placement for resistant deep periodontal pockets. In addition, there is promise using doxycycline to improve glycemic blood levels. Doxycycline, a tetracycline antibiotic, has shown to inhibit the connective tissue-degrading enzymes using a subclinical level of the antibiotic that is not antimicrobial, thus "eliminating the risk of bacterial resistance" (Vernillo, 2003, p. 31S). Both scaling and root planing, Arestin, and doxycycline antimicrobial adjuncts should be considered for the higher risk diabetic patient in managing their periodontal disease.

Diabetic treatments should be aggressive therapy, not observation. It is proven that when periodontal disease infections are treated and the inflammation associated with the disease is eliminated or reduced, it has a positive effect on the patient's glycemic control, whether they are Type 1 or 2 diabetics. It effectively limits and prevents the spread of oral infection.

Equally important for diabetic patients is a rigorous follow-up and preventive maintenance schedule. Those with stable glycemic control require regular periodontal maintenance care at least three times per year. However, unstable glycemic diabetic patients need closer attention and require recare appointments four times per year. The diabetic patient will continue to require close supervision by their dental hygienist and occasional collaboration with their physician for periodontal stability and the prevention of oral complications.

Marcy Ortiz, RDH, BA, has practiced dental hygiene for 24 years, the last 15 years in a geriatric dental practice in Sun City West, Ariz. She recently earned a bachelor's degree in integrative studies from Arizona State University, graduating summa cum laude. She is a member of the Golden Key International Honour Society. She is the current president of Camelback Toastmasters in Glendale, Ariz., earning the Advanced Communicator Bronze and Advanced Leadership Bronze achievement this year. Marcy can be contacted at [email protected].

References

American Diabetes Association. (January 2009). Summary of revisions for the 2009 clinical practice recommendations. Diabetes Care, 32(Supplement 14S-10S), Retrieved from http://www.asmbs.org/Newsite07/resources/execsumm_ada_standards.pdf

Bowen DM. (2010). Collaboration as a philosophy of interdisciplinary health care. American Dental Hygienists' Association (Access), 24(3), 12-14.

Boyd LD. (2008). Commentary on "survey of diabetes knowledge and practices of dental hygienists." American Dental Hygienists' Association (Access), 22(8), 40-43.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes fact sheet, 2007. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/diabetes/pubs/pdf/ndfs_2007.pdf

Cohen DW. Diabetes and oral health: A call to action. Retrieved from http://www.nyu.edu/dental/nexus/issues/summer2003/diabetesacalltoaction.html

Genco R. (2008). Perio medicine: the future of oral health. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene, 6(3), 16-18.

Kandelman D, Petersen PE, and Ueda H. (2008). Oral health, general health, and quality of life in older people. Special Care Dentistry Association, 28(6), 224-232.

Kaplan-Mayer G. (2010). A focus on adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Self-Management, 27(2), 14-20.

Ryan ME, Carnu O, Kamer A. (2003). The influence of diabetes on the periodontal tissues. Journal of the American Dental Association, 134(October), 34S-40S.

Ship JA. (2003). Diabetes and oral health. Journal of American Dental Association, 134(October) 4S-10S. Retrieved from http://www.jada.info/cgi/reprint/134/suppl_1/4S

Slim L, Lavelle C. (2009). RDH inflammation sleuth: The search for clues among systemic links. RDH, (October), 58-69.

Spencer A, Tsokris M. (2005). Maintaining health with age. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene, 3(4): 10, 12-13.

Suzuki JB, Dave S, Van Dyke T. (2007). Chronic inflammation in periodontal diseases: Immunopathogenesis and treatment. Grand Rounds in Oral-Systemic Medicine, 2(3). Retrieved from http://www.dentaleconomics.com/display_article/309340/108/none/none/Oart/Chronic-inflammation-in-periodontal-diseases:-immunopathogenesis-and-treatmen?host=www.thesystemiclink.com

Taylor GW. (2003). The effects of periodontal treatment on diabetes. Journal of the American Dental Association, 134, 41S-48S.

Vernillo AT. (2003). Dental considerations for the treatment of patients with diabetes mellitus. Journal of the American Dental Association, 134(October) 24S-32S. Retrieved from http://www.adajournal.com/cgi/reprint/134/suppl_1/24S

- Burning mouth syndrome

- Candidiasis

- Dental caries

- Gingivitis

- Glossodynia (burning/pain of tongue)

- Lichen planus

- Neurosensory dysesthesias (impaired sensation in feet, hands, or organ problems due to loss of sensation – for example, digestion slowed in stomach)

- Periodontitis

- Salivary dysfunctions

- Taste dysfunctions

- Xerostomia

Source: (Ship, 2003, p. 6S)

Figure 4: Treatment with insulin or oral medication among adults with diagnosed diabetes, United States, 2004-2006:

- 57% oral medication only

- 16% no medication

- 14% insulin only

- 13% insulin and oral medication

Source: (CDC: Diabetes, 2007, p. 3)

Past RDH Issues