Local anesthesia: Tips and tricks for learning and refreshing skills

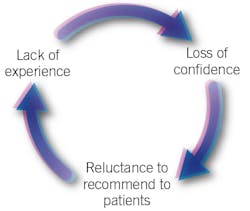

Since the provision of local anesthesia is an important service for our patients, it is necessary for both students and practitioners to develop and maintain the skills and knowledge required for proper and safe administration.

Revisit anatomy and neurophysiology

The anatomically correct 3-D skull model is far more advantageous for feeling and identifying anatomical landmarks and practicing fulcrum placement and angulation for syringe and needle than looking at images alone (figure 2). Life-size skulls with detachable mandibles can be purchased starting around $50. When I ordered mine, I wrote to the manufacturer and explained that I required a skull that accurately reflected the maxillary and mandibular landmarks (e.g., lingula, mandibular foramen, inner ridge, mental foramen, infraorbital foramen, anterior palatine foramen, nasal palatine foramen) and had a removable mandible. Color-coding and labeling was not important for me. What the manufacturer recommended was exactly what I needed for my courses and photography. Reviewing neurophysiology may be accomplished by consulting dental hygiene and dental textbooks, and it is an important process for refreshing knowledge of how dental local anesthetics work and which nerves, teeth, and soft tissues are anesthetized by specific injections.Practice, practice, practice!

It has been said that “practice makes perfect,” but of course, that may be easier said than done regarding delivery of local anesthesia, particularly when the clinician is nervous about the sharp end of a needle. A product has been developed that “bridges the gap” between classroom and patient.1 The Safe-D-Needle (figure 3) has become very popular in the dental and dental hygiene schools as a teaching aid. It is a dental needle with a smooth, round ball modification at the tip, which allows for unlimited noninvasive practice on as many patients as required to gain confidence prior to proceeding with the actual administration of local anesthesia. The clinician is able to practice safe entry and exit of the oral cavity; effective retraction; determination of the insertion point; proper bevel orientation; needle angulation; syringe barrel position; hand positioning on the syringe; stabilization techniques; and simulated rotation and aspiration techniques. Additionally, an instructor or peer partner can make adjustments to the hand and arm of the clinician during practice without concern over a possible needle-inflicted trauma.1Visualization

An important technique to use before and during administering local anesthesia is to visualize the anatomy and each step of the process. Then, while proceeding with the injection, carefully reiterate the steps (silently). This is the method used to teach students, who recite the steps out loud instead of silently. Proper preparation, careful attention to technique, and slow administration contribute to safe, comfortable, and successful administration.

Review product updates

New products become available that improve clinician (and patient) comfort. Not all products are created equal; therefore, it is essential to familiarize ourselves with those products that make administration of local anesthesia reliable, safe, and comfortable for both clinician and patient.

Syringes

Local dental product representatives can show us some of the newer, ergonomic, lightweight, smaller syringes that improve tactile feel and control (figure 4). The smaller oval-shaped thumb rings reduce excess gap to make aspiration easier.2 Since I have small hands, I have never been comfortable with the winged-style syringes until I tried these smaller syringes. What a difference! The size, balance, and weight are very comfortable. Be aware that some of the smallest syringes do not allow for full expulsion of the cartridge, but what remains is less than a stopper full.Needles

Needles with metal hubs must be screwed down tight to avoid loosening, and often the bevel or syringe window is out of position.3 However, plastic hubs adapt well to most syringes, and also to those that are stripped or have defects. They are easy to rotate for aligning the bevel and are less likely to remove the syringe hub. The literature supports the use of 25-gauge and 27-gauge needles to ensure less deflection, lower needle breakage, and more reliable blood aspiration than 30-gauge needles.3,4 For many years, studies have shown that patients are unable to perceive a difference in comfort between 25-gauge and 30-gauge needles.5-7

Anesthetic agents

Reviewing current literature and attending courses by experts in local anesthesia is a good way to keep current on the pharmacology and practical use of available local anesthetic agents, as well as the maximum recommended doses associated with them. Agent selection for nonsurgical periodontal therapy procedures should be based on length and type of procedure, the patient profile, and the need for hemostasis. The rate of biotransformation, elimination half-life, and effects on various organs (e.g., liver, kidneys, heart) should be appreciated. Articaine, for example, has less impact on the liver because it is metabolized primarily in the plasma and, importantly, the elimination half-life is significantly less than the other amide local anesthetics. In the past 10 years, the US market share for articaine has grown while the market share for lidocaine has declined. Although lidocaine remains the most popular dental local anesthetic in the United States, articaine ranks a close second.3,8

Take a formal course annually

Local anesthesia update courses are available in a variety of formats (online, DVD, and traditional lecture, some with hands-on components) and can be useful for learning important new information and rectifying common errors. The opportunity to discuss techniques and practice them with colleagues is priceless. Another avenue worth pursuing is to contact the local dental hygiene education program director regarding independent study courses that may include didactic and clinical components.

Assess personal techniques

We should regularly assess our injection techniques and practice with the typodont/skull and Safe-D-Needle. Common clinical errors include insufficient retraction, poor lighting, improper angulation, needle movement at target, premature/rapid deposition, poor thumb position for aspiration, needle movement during aspiration, and weak fulcrum.

Forty years ago, I began providing local anesthesia for my patients. I can’t imagine practicing without it. I have learned through teaching and working in private practice settings that even the most experienced clinicians should take time to frequently reassess their skills and stay current with armamentarium and techniques via a variety of resources. The provision of local anesthesia for patients is not difficult, but it does require maintenance of skill and evidence-based practice.

References

1. Home page. Safe-D-Needle website. http://www.safe-d-needle.com/home.html.

2. Aspirating syringes. Septodont website. https://www.septodontusa.com/products/aspirating-syringes.

3. Logothetis D. Local Anesthesia for the Dental Hygienist. St. Louis, Missouri; Elsevier: 2017.

4. Malamed S. Handbook of Local Anesthesia. St. Louis, Missouri; Elsevier: 2013.

5. Hamburg HL. Preliminary study of patient reaction to needle gauge. NY State Dent J. 1972;38:425-426.

6. Brownbill JW, Walker PO, Bourcy BD, Keenan KM. Comparison of inferior dental nerve block injections in child patients using 30-gauge and 25-gauge short needles. Anesth Prog. 1987;34(6):215-219.

7. Flanagan T, Wahl MJ, Schmitz MM, Wahl JA. Size doesn’t matter: Needle gauge and injection pain. Gen Dent. 2007;55(3):216-217.

8. Malamed S. Renaissance in Local Anesthesia [course]. San Marino, California: International Dental Seminars; 2018.

Laura J. Webb, MS, RDH, FAADH, is faculty emerita and former founding director of the dental hygiene program at the Truckee Meadows Community College in Reno, Nevada. An experienced clinician, educator, and international speaker, she owns LJW Education Services (ljweduserv.com) and has provided educational methodology courses, accreditation consulting, and continuing education courses for 18 years. Laura enjoys speaking on pain-control topics. She was recipient of the 2012 American Dental Hygienists’ Association Alfred C. Fones Award. Laura can be reached at [email protected].

About the Author

Laura J. Webb, MS, RDH, FAADH

Laura J. Webb, MS, RDH, FAADH, is an experienced clinician, educator, and speaker who founded LJW Education Services (ljweduserv.com). She has provided educational methodology courses and accreditation consulting services for allied dental education programs and CE courses for clinicians. Laura has frequently spoken on the topics of local anesthesia and nonsurgical periodontal instrumentation. She was the recipient of the 2012 ADHA Alfred C. Fones Award. Laura can be reached at [email protected].

Updated May 2023