Incorporating air polishing into daily practice

A fresh look at the benefits encourages routine usage

By Lauren Crasto, BSHS, RDH

If the mere mention of air polishing brings you back to your days in dental hygiene school, you are not alone. Kris Johnson, BA, RDHAP, recalls an early experience with air polishing, saying “I recall having a brief overview of air polishing and getting to use it in the clinic—just one time—when I was a student of dental hygiene back in 1993. At the time, I had mixed thoughts: Wow! That stain came off like magic, what a mess, and finally, it’s not worth the effort to assemble the unit, only to have my patient complain about how it tastes.”1

If you do not utilize an air polisher in your office, consider this: How are you compensating for being without one? Are you exhausted after an especially difficult prophylaxis appointment? Are you frustrated with the final result of prophylaxis performed on periodontal patients? Can implementation of air polishing ease your schedule, improve your day, and enhance patient treatment outcomes?

In a Journal of Evidence-Based Dental Practice Technology article, Cynthia Gadbury-Amyot warns hygienists that they could see a decrease in their demand if they fail to adapt to the technological advances in the industry.2 While air polishing is not new technology, a fresh look at its benefits may help you keep pace with other savvy dental professionals in the industry. Air polishing is a valuable tool that every dental hygienist should utilize regularly as applicable.

Preparedness is essential. Rather than introducing the air polisher midway through the appointment, incorporate its use into the dental hygiene treatment plan for the patient. When reviewing your patient schedule for the day, identify patients with crowding, heavy stain, or orthodontic appliances, also noting patients scheduled for sealant placement, those with implants, or on periodontal maintenance programs.

According to Shirley Gutkowski, BSDH, RDH, learning to use polishing options available today “can make an oral health provider a true patient advocate by keeping the enamel sound.”3 A study comparing air polishing to traditional rubber-cup prophylaxis with polishing paste concluded that while they were equally efficient in stain removal, there were some notable differences between the two methods. The traditional prophy cup with abrasive paste can be laborious, time consuming, and may be less effective on orthodontic appliances and interproximal surfaces. Conversely, air polishing offers rapid removal of stain and plaque, results in less hypersensitivity, less operator fatigue, and increased access to pits and fissures. Gutkowski indicates in response to the idea the enamel has the ability to heal itself that “we are still obligated to use the least damaging agent to remove stain,”3 adding that air slurry polishing methods are the best way to remove stain while preserving enamel.

In my personal experience as a dental hygienist for 15 years, I have yet to encounter a patient concerned with biofilm removal. Dental hygienists can appreciate the value of biofilm, plaque, and calculus removal. However, many patients ascribe to the belief that a “good cleaning” leads to a better appearance.

While traditional rubber cup polishing may be sufficient for many of our patients, we are limited by the inability of the rubber cup to access all of the areas where stain is present, such as in sulcular and interproximal spaces. Having an air polisher at your disposal can drastically improve polishing results for the patients with heavy extrinsic stain from tobacco, coffee, red wine, and poor oral hygiene. By utilizing the technology, our patients should be more satisfied with the results and spend less time in the chair. Practitioners should also experience less fatigue in removing difficult stain.

With regard to sealant placement, rather than the rote setup with pumice and a rubber cup, consider treating the dentition with an air polisher. According to Marilynn Rothen, MS, RDH, air polishing is “more effective than rubber cup polishing when cleaning the tooth surface prior to etching for sealant placement, resulting in enhanced bond strength.”4 Sodium bicarbonate is the preferred powder for polishing occlusal surfaces prior to sealant placement.

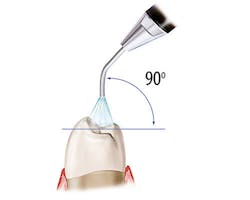

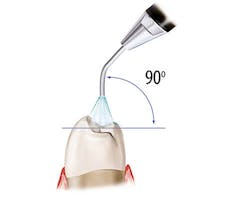

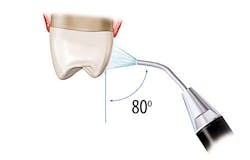

Figure 1: Recommended angulation for air polishing. Images courtesy of The Next DDS (thenextdds.com).12

Safety concerns

Subgingival air polishing is safe and effective for shallow to moderate pockets. However, there are newer nozzles designed to reach a depth of up to 10 mm. Studies show that when used in conjunction with hand/ultrasonic scaling (because air polishing will not remove calculus), the effects include decreased bleeding on probing (BOP), decreased pocket depths, decreased bacteria in the pocket/sulcus, and increased patient comfort. Furthermore, for patients with peri-implantitis, air polishing with glycine powder after non-surgical treatment reduced BOP scores by 24%.5

Specially designed handpieces are required to safely and effectively use the air polisher subgingivally. Improper adaptation of handpieces designed for supragingival polishing can lead to iatrogenically induced facial emphysema, a rare side effect that occurs when air is introduced into the subcuatenous tissues. Patients experience swelling, tenderness, and pain that usually resolves without treatment within seven days.

We have identified which patients in our schedule could potentially benefit from air polishing, but we must ensure that there are no contraindications, such as the following:

• Patients with respiratory or swallowing difficulty

• Adrenal deficiencies

• Acute gingival conditions

• Other infections

• Use of mineral corticosteroids, potassium supplements or antidiuretics are not appropriate candidates for air polishing.

If no contraindications for use, proceed with selecting the appropriate powder: Aluminum hydroxide, bioactive glass, calcium carbonate, glycine, or sodium bicarbonate. Gutkowski stresses the importance of swapping out the air polishing powder based on the patient in the chair.3 For example, a patient who cannot use sodium bicarbonate because of a salt restricted diet would require an alternative such as aluminum hydroxide. Or, a patient with hypersensitivity may respond well to air polishing with a powder composed of bioactive glass. Bioactive glass is categorized as a rehabbing powder for its potential to promote remineralization in areas of breakdown.

In 2015, Sandra Pence stated that low abrasive powders, such as glycine, can remove plaque from 3-4 mm pockets (up to 10 mm with a special hand piece nozzle), which makes it an effective treatment for patients on periodontal maintenance.6

Air polishing device usage

In order to prepare the patient for air polishing, dental hygienists should do as follows:

• Operators should provide patients with a moisture resistant apron for the neck and upper torso.

• Apply lip balm to protect the lips from the drying effects of the powder.

• Use gauze on the patient’s tongue to minimize the taste.

In addition to their usual personal protective equipment, operators should don a hair cover, long sleeve overgarment, and eyewear.

Clinicians should not attempt to insert subgingivally if lacking the proper equipment or have not been properly trained in this technique. Diane Daubert, PhD, MS, RDH, instructs practitioners to insert the nozzle until resistance is felt, and then to move back to allow 3 mm space between bone and tip of nozzle.7 Activate the tip and move over the entire root surface, using a circular motion for five seconds per site. The newer devices have tips with multiple outlets for the powder so that it is directed at the entire sulcus space, not just the root itself.

The recommended angulation for air polishing supragingival tooth surfaces is pictured in Figure 1, which shows 90 degrees for occlusal surfaces, 60-degree angulation for anterior teeth, and 80 degrees for posterior tooth surfaces. Activate the tip and use circular strokes 3–5 mm away from tooth for three to five seconds per tooth surface, carefully avoiding sulcus spaces or pockets.

According to Patil, et al., “Many investigators agree that intact enamel surfaces are not damaged when stain removal is accomplished with an air polisher, even after 15 years.”8 Chowdhary and Sharma explain that of all of the factors involved in air polishing, time has the strongest effect on whether a defect will result from air polishing; therefore exceeding 3–5 mm time limit per tooth surface is not recommended.9

Various models are available in both tabletop and handpiece designs. In my experience, I have used a handpiece attachment that was convenient for moving between my two treatment rooms. However, many of the tabletop units have the ability to move between ultrasonic scaling and air polishing seamlessly, which can be a real time-saver.

Regardless of the choice, take the time to become knowledgeable in all of the device’s features. Caren Barnes, MS, RDH, said of dental professionals that “the most accepting of air polishing were the ones that took the time to learn the correct techniques for use.”10 I encourage you to use the information in this article as a guide for adding air polishing to your armamentarium.

References

1. Johnson K. Air Polishing Has Changed—So Why Hasn’t the Dental Hygiene Curriculum? DentistryIQ website. http://www.dentistryiq.com/articles/2016/08/air-polishing-has-changed-so-why-hasn-t-the-dental-hygiene-curriculum.html. Published August 16, 2016.

2. Gadbury-Amyot C. Technology is a Critical Game Changer to the Practice of Dental Hygiene. J Evid-Based Dent Pr. 2014;14:240-245.

3. Gutkowski S. Polishing Without Harm: Safer Concepts are Emerging in Enamel Polishing. RDH website. https://www.rdhmag.com/articles/print/volume-36/issue-9/contents/polishing-without-harm.html. Published September 19, 2016.

4. Rothen M. The Tipping Point for Air Polishing. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene website. http://www.dimensionsofdentalhygiene.com/2016/10_October/Features/The_Tipping_Point_for_Air_Polishing.aspx. Published October 2016.

5. Schwarz F, Becker K, Renvert S. Efficacy of air polishing for the non-surgical treatment of peri-implant diseases: a systematic review. J Clin Periodont. 2015;42(10):951-959. doi:10.1111/jcpe.12454.

6. Pence S. The Evolution of Air Polishing. Dimensions Dental Hygiene website. http://www.dimensionsofdentalhygiene.com/2015/03_March/Features/The_Evolution_of_Air_Polishing.aspx. Published March 2015.

7. Daubert DM. Subgingival Air Polishing. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene website. http://www.dimensionsofdentalhygiene.com/2013/12_December/Features/Subgingival_Air_Polishing.aspx. Published December 2013.

8. Patil SS, Rakhewar PS, Limaye PS, Chaudhari NP. A Comparative Evaluation of Plaque-Removing Efficacy of Air Polishing and Rubber-Cup, Bristle Brush With Paste Polishing on Oral Hygiene Status: A Clinical Study. Journal of International Society of Preventive & Community Dentistry. 2015;5(6):457-462. doi: 10.2310/8000.2013.130756.

9. Chowdhary MR, Sharma RR. Air Polishing: An Update. International Journal of Maxillofacial Research. 2015;1(1):22-34.

10. Barnes CM. Air Polishing: A Mainstay for Dental Hygiene. Dental Academy of CE website. https://www.dentalacademyofce.com/courses/2423/PDF/1305cei_Barnes_RDH_final.pdf. Published 2013.

11. Hongsathavij R, Kuphasuk Y, Rattanasuwan K. Clinical Comparison of the Stain Removal Efficacy of Two Air Polishing Powders. European Journal of Dentistry. 2017;11(3):370-375.

12. Reprinted with permission of The Next DDS. Original images available at http://www.thenextdds.com/clinicalimages.aspx?catid=624&id=4294971482&t=i.

Lauren Crasto, BSHS, RDH, graduated from the New York City College of Technology with an associate of science degree in dental hygiene. She graduated with honors in 2018 from Rutgers School of Health Professions, where she successfully completed an intensive clinical internship as a faculty intern. Currently she is pursuing her master’s degree in health professions education at Rutgers. Crasto has experience working in private practice and as a consultant for Milestone Scientific Inc. She is an active member of the American Dental Hygienists’ Association and lives in New Jersey with her husband and two sons.