From the ivory tower: Promoting acceptance of dental products

By Edward F. Rossomando, DDS, PhD, MS, Professor and Director, Center for Research and Education in Product Evaluation (CRETE), School of Dental Medicine, University of Connecticut, Farmington, CT

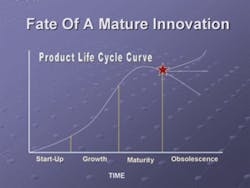

It is almost axiomatic that, following the introduction of most new products to market, sales climb rapidly. Figure 1 graphically illustrates the relationship between sales as a function of time after introduction of the product to market. Traditionally, a product’s life cycle is divided into stages - as illustrated in Figure 1 (see below) - that include start-up, growth, maturity, and finally, obsolescence. As shown, shortly after introduction of a product, there is a slight lag during the start-up phase, followed by a rapid rise in sales during the growth phase. Growth, and the increase in sales, continues usually until the product reaches maturity. At this point in the product’s life cycle (indicated by the star on the illustration), sales can decline (as the product enters the obsolescence phase), continue at a constant rate, or, in some cases, increase. These three options are shown in the illustration by the sales’ projections after the star. While these possible fates for a product after it reaches maturity are well known, the variables that determine which path a product will take are not. In fact, it is when sales begin to slow that most company executives must make a difficult decision - should sales of the product be terminated or might sales be enhanced by additional investment?

What information does a company executive need to make a rational decision? Assuming the product has not outlived its usefulness and has not become obsolete or displaced by a competitor, the executive needs to understand the reason for the initial “burst” in sales and the eventual leveling off. The traditional view attributes this to the product itself - the initial sales reflecting acceptance and utilization of the product by all customers in the market and the leveling off to the product’s displacement by a competitor with a better product.

An alternative view is that the phenomena reflect not the product, but rather the customer segmentation. In the alternative view, the initial burst of sales is due to purchasing by those early adopters within the customer population. The validity of this explanation can be determined in part by an analysis of the sales numbers. The early adopter population makes up between 4 and 6 percent of any customer population. Assuming there are about 150,000 dentists in the U.S., if sales begin to level off after about 6,000 to 9,000 units are sold, the decline in sales might reflect customer interest rather than product maturity and obsolesce. If the decline in sales were a result of a lack of customer acceptance, it would suggest that the marketing strategy has not been successful in capturing the interest of those in the “early” and “late” customer categories.

Why might this be? Studies pending publication conducted at the Center for Research and Education in Technology Evaluation (CRETE) suggest that the lack of acceptance of a new product by the majority of customers is a function of human barriers, not product obsolesce. Of the many possible barriers, CRETE scientists have identified three as most important - financial, educational, and procedural.

A financial barrier exists when the magnitude of the investment is beyond what the practicing dentist can comfortably afford. Some examples where financial investment could be a barrier include CAD/CAM technology and the dental laser. While the acceptance (and therefore sales) of both technologies is accelerating, the significant costs involved continue as barriers to acceptance.

An educational barrier exists when the product or technology is outside the educational experience of the dentist or dental office personnel, including the office manager. For argument’s sake, imagine how difficult it would be to sell sterilization products or technologies to a dentist who has no knowledge of the germ theory of disease. Not surprisingly, the absence of an educational background can prevent the acceptance of a new product or technology. There are many new products on the verge of entering the marketplace that rely on knowledge of biochemistry and molecular biology. These biotechnology-based products include vaccines, bioscaffolds, and laboratory-grown teeth. Acceptance of such products will be difficult unless dentists and dental office personnel receive some education in the basic science underlying these innovations. Educating the dentist is not sufficient. CRETE investigators found that any of the dental office personnel can affect the acceptance of a new dental product. Continuing education courses are critical to update all those in the dental office, including the dentist, hygienists, dental assistants, and office manager.

Procedural barriers also exist within the dental office. For example, the dental office team will reject new products if patient flow is compromised. Any innovation, regardless of its effectiveness, will be unacceptable if it impedes the flow of patients through the dental office. Similarly, the dental office team will reject any new product that compromises cash flow, even if only temporary.

The company executive studying the sales chart shown in Figure 1 needs to decide between the alternative explanations - is the decline in sales because the product is obsolete or because the majority of customers have not accepted it? Clearly if the numbers indicate the decline is a result of lack of acceptance, then our executive should ask additional questions to determine if one of the three barriers - financial, educational, or procedural - might be responsible. Depending on the answer, our executive can make a rational “go” or “no go” decision on additional investment. Information on which of the three alternatives is the barrier can be significant in the design of the next phase of the sales campaign. Thus, if the barrier is found to be educational, investment in continuing education courses could be the answer. Keep in mind courses are needed not only for dentists, but for other office personnel as well. In fact, many dental companies, both manufacturers and distributors, sponsor continuing education courses for just this reason.

How might such information be obtained? Surveys, properly constructed and analyzed, have proven useful. Focus groups are also a standard technique. These techniques and many like them rely on information obtained after the product has been introduced. CRETE has taken a different approach. Our analysis suggests that if the human barriers can be identified prior to introducing the product to market, the sales of a product can be extended beyond the initial burst and sales growth maintained by developing a marketing strategy that promotes acceptance by a majority of customers.

When CRETE performs an analysis of a product prior to its launch, company executives need no longer resort to tea leaves or séances to design its marketing campaign - there are more scientific methods available.

Editor’s Note: Dr. Rossomando may be reached by e-mail at [email protected].