Mrs. Slovotski's visit

Here comes the van with Mrs. Slovotski aboard. The van that brings the elderly from the long-term care facility about 15 miles from here is almost always late. When it does arrive, a new attendant is driving. Although our location is not very difficult to find, somehow the drivers always get the directions mixed up. Mrs. Slovotski lives in one of the long-term care facilities that doesn't have a dentist on-site or even a general dentist who oversees the oral health of the residents.

This long-term care facility is representative of the majority; 60 percent of the facilities have no professional oral care provider at the site. The family's dentist usually is assigned to take care of the resident, and that's how Mrs. Slovotski came to us.

I think my room is ready as I look around. I had to move the patient chair to accommodate the wheel chair. When we get residents from the long-term care facility, we never know exactly with what we're going to be presented. I never know if the patient can move from chair to chair. I do not know if I will be doing stand-up hygiene, or bent-over-funny hygiene. There are some standard things that I know. For example, I won't be using my Prophy Jet on the patient. I won't be on schedule for the rest of the afternoon, and I will have a stiff back when I'm finished. It isn't anyone's fault; it just is. I also know that when I take out her prosthesis it will have a heavy coating of breakfast, lunch, and dinner. She will have root caries, and she will be happy and thankful that she is here to see the dentist.

She is on my schedule today because her last prophy was 18 months ago, and she is at the office today because somehow her lower partial was lost. The records indicate that she was ambulatory then; now she is strapped to a wheel chair to keep her from falling out. By the chuck on the seat of the chair, it appears that she may be incontinent. Thankfully, it's warm out today, and the attendant won't have to fight her out of a winter coat.

I open the door to the reception room and greet them both. The attendant wheels Mrs. Slovotski right into my treatment room. We'll do what we can today.

The attendant hands me Mrs. Slovotski's envelope. My heart sinks as I feel the weight of it. It contains her health history, every medication she's taking, the dosage, and when it was given. It also usually contains some other paperwork, emergency contacts, and the dreaded DNR - Do Not Resuscitate. Mrs. Slovotski's envelope did not contain a DNR, thank goodness. Even worse, though, is a three-page list of medications. The copies are barely readable, and the first two letters of each medication are cut off all the way down the second sheet. All I can do is shake my head. From what I can make out, she is on at least four medications that will cause xerostomia. She is taking Meclizine, a medication for vertigo that explains the strap to hold her in the wheelchair.

Mrs. Slovotski tells me that she only has three teeth. She then continues with the history of how she lost each and every individual tooth. I ask her to remove her upper denture. She informs me that it's a little loose; she has to use paste to hold it in. As she takes it out, pink goo makes a thin string from her mouth to the denture. The tension in the string breaks. Half of it snaps to the denture, and the other half to her lip. She licks it off her lip. Sure enough, the denture is coated with various levels of masticated decaying debris. I wonder to myself what kinds of pathogens a person could isolate from that mess - pneumonia for sure, e. coli probably, and more than likely a good helping of staph and influenza.

Kicking and screaming

Residents in long-term care facilities have markedly higher plaque scores than people who live independently. There are many reasons for this, including mental and physical shortcomings. Another reason is that people who are trained as certified nursing assistants are taught to take care of the mouth as a cosmetic procedure. In school, they practice on each other in the unit that includes nail and hair care. Reports tell us that certified nursing assistants get as excited about oral care as they do about giving enemas.

Only dental care professionals know that the mouth is a cesspool with more bacteria than the other end, and that oral care should be elevated to wound care. Researchers today are studying the effects of frequent elimination of oral plaque as a means of decreasing nursing home pneumonia outbreaks.

The certified nursing assistants' main reason for not doing oral care is that they are afraid of being bitten, not because of time constraints. Dealing with noncompliant residents is another reason. It's pretty hard to clean someone's teeth when they do not want to have it done. Just think of three-year-olds clamping their little lips together in a tight line, vermilion border all but a memory. Their little legs pumping and kicking, heads turning right and left at the speed of sound, the sound of screaming NOOOOOO. Imagine this in a person seven times the weight or more and triple the height. You can understand their hesitation!

Published studies tell us that certified nursing assistants are not uneducated. Almost all have finished high school, and over half have some post-secondary education. They really like what they do, as we do, and certified nursing assistants are interested in providing the very best care for their charges.

How can dental health care providers expect more when certified nursing assistants are taught that cleaning the mouth is as important as braiding hair? They need to know it's wound care. They need to know that the mouth is a portal for infections. They should know that the germs that live in the mouth, when not removed daily and properly, are going to cause them a great deal more work taking care of a critically ill person.

Toothettes are popular in long-term care facilities. Remember toothettes - those little sponges on a stick? The only time that a toothette is as good as a toothbrush is when it is soaked in chlorhexidine. This is not to say that the debris is removed, but only that the plaque is probably dead. But chlorhexidine isn't used. Alcohol must be avoided, not just because it dries the tissue, but because the residents like the effects when taken internally. The nurses I've contacted regarding this issue all say that chlorhexidine is cost prohibitive when compared to the mouthwash they currently use at their facility.

The dental profession is aware of the problems concerning certified nursing assistants in relation to oral care of the people living in the facilities, as well as their care in hospitals. We know it is less than optimal, and we know why it is so. Now we have to formulate resources to let medicine know it, and make an action plan for change. Will it be better or a different type of education of the nursing assistants? Will it be addressing the Surgeon General's issue of access to care? Will there be supervision changes to allow hygienists to lead oral care teams in the facilities? What is the answer?

Her last grasp at independence

I asked the attendant to remain in the room as I took Mrs. Slovotski's offensive denture to the ultrasonic to be cleaned. When I returned, the two were chatting gaily. It was obvious to me that the attendant liked her. I had Mrs. Slovotski tip her head back so I could look into her mouth. Her palate was bright red - most probably a yeast infection - and the corners of her mouth were red as well (angular chelitis, with a touch of yeast there, too). The three lower teeth were covered in plaque, the kind that looks like small curd cottage cheese. I did not bother with hand instruments; I polished the plaque off and tried to educate the attendant. Her interest seemed to be contrived.

Mrs. Slovotski cheerily told me that she did her own oral care. It was clear to anyone that she was not monitored in regards to this task. She was convinced that she could take care of her mouth. For her, it was a sign that she was still independent in some small way. Her legs were "bad" so she had to have someone schlep her around in a wheelchair, and her vertigo was so bad that she had to be strapped into it. She could not dress herself because she could not raise her arms up over her head, and the nurses on the floor were afraid that she would fall over. She couldn't chew because somehow her lower partial denture was misplaced, and the upper denture fit loosely - not to mention that nothing tasted good to her anyway. All she had left was feeding herself and taking care of her three tall teeth.

While I was waiting for the doctor to come and do the exam, I pondered the pages from the envelope. I wonder to myself if anyone is monitoring the drug interactions. Are any of these medications causing the need for another medication? I wonder if I should try to figure out the names of each medication on the second sheet, where the first two letters were cut off during the copying. I notice that she is taking an OTC antacid as a calcium supplement. She had taken her antibiotic premedication. She is on cumadin and disipramine, also Prozosin. It was noted that she fell last week and had a nasty bruise on her left hip. She is also taking Imodium, glucophage, and cortisone cream is applied to a private itchy spot.

My contribution to The Envelope

The doctor came in to do the exam. Under the coating of plaque was decay. Yes, she needed three fillings. We add to her list of medications: Chlorhexidine swab once a day for yeast and decay, Xylitol mints up to five times per day for yeast and decay, and fluoride lozenges BID for decay.

Just then, the dental assistant came in with Mrs. Slovotski's denture. I picked it up to see if it needed a once over with the Prophy Jet. Inside the plastic was the typed label of "Horowitz." How undignified! If this is what I have to look forward to in my old age, then count me out. I decided years ago that there was no way that I was going to become old. I'm sticking with that decision.

I polish Mrs. Slovotski's denture, trying not to shake my head. We would do no real treatment today. Yes, she needs to have a new lower partial. She's diabetic and she needs to maintain a healthy diet, which is pretty hard to do without teeth. I decided that I wouldn't look up the medications that were cut off of the sheet. For these noninvasive procedures, I could not see expending that much time and energy on a project that wouldn't effect the treatment provided. They send an updated envelope at every appointment.

The attendant could not make the appointments for Mrs. Slovotski. So we wrote up the treatment plan and entered the treatment rendered today on a sheet provided by the facility.

As the hygienist, I'm supposed to make hygiene recommendations on this sheet. I ponder. Should I really write on this sheet that Mrs. Slovotski should have help brushing her teeth twice per day? If I do, will anyone see it? If they see it, will they become incensed, because they think they already do it? If they do follow my recommendations, will Mrs. Slovotski feel the crush of dependence?

I do my sworn duty and write on the page to go into the envelope: Patient needs to have help brushing remaining teeth mornings and evenings. A power brush is advisable. Dentures must be cleaned of all debris after meals; the denture labeled "Slovotski" must be returned to resident.

That sheet will be put into her chart at the facility. I do not know what will happen to it, but I have a suspicion. I've seen those charts. Over one-inch thick, every page is filled with writing (font size eight), circles, check marks, and a myriad of other notations.

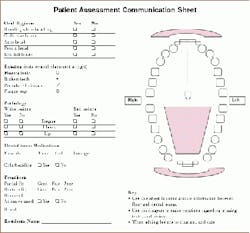

I would rather have a sheet that would be easily recognizable as a dental sheet. A single sheet that would be available as a communication tool between the dental team and the team at the facility. An example is on the next page.

To use it, we could mark on the sheet which teeth the resident has, if any are broken, if the dentures fit, if they can't be made to fit any better, and the location of any lesion or mark. This would let them know if we have already noted a soft tissue deviation or a broken tooth. They, in return, could mark up the sheet to let us know if there were any problems.

Mrs. Slovotski and her attendant return to the van. She'll go back to her usual life there. I hope that the nursing assistants will notice that the denture looks different now. I hope they become alarmed when they notice the name in the denture is wrong. I, of course, do not have much time to wonder about it since my next patient has arrived.

When my mind wanders

On my way home, I start to wonder about what will become of the people who have teeth. The research shows us that if you have missing teeth your health risks are very much increased. Stroke, heart attack, COPD, all of these are conditions we have associated with increased age. Now we have to think of those when we have a patient with missing teeth. Some report that missing teeth is a better risk indicator for those diseases than smoking! As time goes by, residents in long-term care facilities will have more and more teeth. Will that mean that those residents will be at a lower risk for systemic ailments? Will it mean that if their oral cavity is not maintained at optimal levels and they begin to lose teeth, their risk for those other ailments will increase? Will their risk increase rapidly?

It has been reported that people in long-term care facilities and geriatric individuals have the same risk for decay as children in unfluoridated areas. People still lose more teeth to decay than periodontal disease.

Realistically consider the 82-year-old man that walked into your treatment room last week with a full complement of natural, albeit crowded, teeth. He may be in the care of someone today who has no real grasp of the enormity of the consequences of improper oral care. If he has to be intubated, thrush is possible. Then Nystatin will be prescribed, a medication loaded with sugar. The sugar therein, and the inadequate plaque removal is a recipe for decay. Who's going to know that this man has a carious lesion? You know the one. Mesial of number three, under the crown that the doctor was going to "watch." Who's going to repair it? Who will report to the dentist that he has been hospitalized? He was ambulatory a few short weeks ago; now he's totally dependent. Even if it's for a short hospital stay, total recovery will not be rapid, if it is attained at all.

The situation is circular. We in dentistry try to help people keep their teeth until they're on the wrong side of the grass. While the researchers play tennis with the treacherousness of periodontal disease, I believe it safe to generalize and say that people with teeth are healthier than people without. If these people are one of the 40 percent of the population that enter into a long-term care facility, will it be too much trouble for undereducated medical personnel to take care of their teeth? Is it really too much trouble? People with teeth are healthier.

As hygienists, we are qualified to go to the directors of nursing or staff development personnel in these facilities and ask to present oral care information. Showing the certified nursing assistants how to do it won't address the issue. Explaining why, will. In our state, nursing assistants are required to have continuing education credits in oral care, at least once a year. Care facilities must provide in-service presentations for their staff. The staff development nurse's voice changes to relief when offered free or inexpensive services related to continuing education for the staff.

Mrs. Slovotski and her friends are counting on us.

Shirley Gutkowski, RDH, BSDH, has been practicing in Madison, Wis., since 1986. She is a frequent contributor to the Internet lists, [email protected] and sci.med.dentistry, She also was recently published in Nursing Case Management. Gutkowski presents seminars for nurses and nursing assistants on oral infection control in long-term care facilities. She can be reached by e-mail at shirdent@aol. com.