Lasers in Hygiene

Shine the healing light

by Liz Lundry, RDH, RDHMP

This is an amazing time to be a dental hygienist! I started my career as an orthodontic assistant in 1975. I always knew I wanted to be a hygienist, but I didn't know how fun and rewarding this career would be, as well as how much it would evolve as a science through technological advancements. When I became a hygienist in 1979, our treatments primarily involved hand instruments, prophy angles, and ultrasonics for heavy supragingival calculus removal. Microultrasonics were not available then, and our treatment focus was to remove calculus and get patients to floss. What a challenge!

Due to advancing science, we now know so much more about the periodontal disease process. We treat with a greater understanding of the bacterial role and the destruction caused by the immune response itself. With that knowledge, it behooves us to examine all technologies available, incorporating them into daily care.

Our goal, after all, is to better serve our patients, improving both their dental health and overall health. We understand the systemic link and need to look beyond simply what is going on in the periodontal pocket. Periodontal disease is a chronic inflammatory disease for which there is no cure. Anything we can do to get better clinical results and compliance from our patients will assist in keeping our patients in remission.

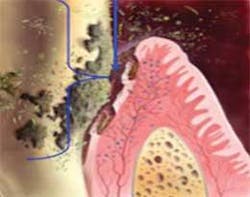

Let's look at what is happening on a microbiological level in the pocket. Virulent bacteria — namely the red complex, P. gingivalis, A. actinomycetemcomitans, and T. forsythia — have the ability to invade the tissue wall for access to blood vessels and, therefore, the entire body. Reduction or elimination of these potentially deadly bacteria should be our primary goal.

As a clinician, I was given the opportunity to use a soft tissue laser during nonsurgical periodontal therapy about 10 years ago. Since adding the laser to treatment plans, I have observed superior healing as well as better acceptance to therapy from my patients. We all know how difficult it is to get our patients to come back for more than a prophy or maintenance procedure. When the laser is offered, the patients are more open to comprehensive treatment. They know they are getting more value. Many clinicians who use lasers have observed enthusiasm and better case acceptance from patients.

Taking the fight to the sulcular wall

The laser is quite simple to use, and it does not take a lot of the appointment time to apply. The function of the laser is to reduce the bacterial population in the pocket, including the sulcular wall. Various studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of the laser to decontaminate periodontal pockets.

By passing the laser along the tissue wall, we are also able to remove diseased tissue that has been invaded with bacteria. This procedure is conducted after thorough debridement of the root surface. Removal of calculus should be carried out utilizing primarily ultrasonics. According to Dr. Esther Wilkins, ultrasonics should be used about 80% of the time and hand instruments about 20% of the time. Better healing will be achieved if ultrasonics are used before and after hand instrumentation to remove clotted blood and loose calculus chips. This will leave a cleaner wound site and promote better healing. The ultrasonic will also kill biofilm on the root surface.

Now we are ready to focus on the sulcular wall itself. The laser utilizes light energy, which creates heat. When used at the appropriate setting, the laser will remove only edematous, infected tissue while killing the biofilm present in the tissue wall.

Different lasers (the word is an acronym for light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation) will have different properties based on its medium. The medium is the element used to give the laser its characteristics or tissue specificity. The element may be in the form of a mineral, gas, or liquid. Depending on the medium, the laser will interact with different target tissues.

The laser of choice for nonsurgical periodontal therapy is the diode laser. The medium for the diode is aluminum, arsenide, gallium, or other combinations. in the form of a computer chip. The diode laser will interact specifically with water and pigment. This is exactly what is present in an infected periodontal pocket: hemoglobin (pigment) and lots of fluid or edema (water).

When used at the appropriate settings (wattage), the diode laser will only target infected tissue. Clinicians using lasers sometimes actually see edematous tissue shrinking in front of their eyes as the fluid is dehydrated. The gingiva usually looks better immediately. The laser will also seal blood vessels and lymphatics, and because of this, postoperative discomfort is greatly reduced. In addition, hemostasis may be achieved during laser use.

Anesthetics should be used to ensure patient comfort. Lasers utilize heat to denature proteins and remove edematous tissue. This is not a pleasant sensation, and it is not advisable to proceed without anesthetic. There is no excuse for causing our patients any discomfort in 2010. Let's use the many options available today: injections or needle–free anesthetic.

Modern diode lasers have adjustable presets making them very easy to use. Having said that, it is imperative that the clinician complete and participate in a hands–on laser safety training course. When the laser is used improperly, it can cause tissue damage. When the appropriate parameters are implemented, the laser is safe and will degenerate only edematous tissue, leaving healthy tissue intact. This is not like the lasers we see in science fiction movies. You can't shoot someone down with a soft tissue laser!

The best laser courses include adequate time with live patients so that the clinician is confident when seeing patients back in the practice. As a certified laser trainer with the JP Institute, I customize in–office laser training programs. Participants receive safety and technique instruction with whatever type of laser is available in the practice.

In addition to the clinical skills, it is important to use proper verbiage to communicate with the patient and to understand how the laser affects treatment planning. JP workshops, whether in–office or in a seminar setting, always include verbal skills, business systems, as well as clinical aspects of advanced therapy. There are many components to successful implementation of any technology in the dental office and the whole team needs to be involved for continuity and success.

Another reason diode lasers are a good choice for nonsurgical periodontal treatment is their affordability. A diode can be purchased for as little as $3,000. When the laser is added to therapeutic procedures, the fee for the treatment is increased by $60 to $100 per treatment. Because of the production growth, the cost of the laser is not a factor. The dental team is offering a higher quality of care. The use of the laser often accelerates patient healing, reducing the need for more advanced and costly procedures.

Those of us who use the laser observe greater pocket reduction and better long–term stability. Patient acceptance is excellent, especially if the patient has had root planing in the past and has fallen out of remission. We can now offer a more advanced and effective option. This approach makes sense to a patient who may be discouraged about a previous procedure that they incorrectly perceive to have been a failed treatment. Let's keep reminding our patients that periodontal disease is a chronic condition that is episodic. It's not their fault, and we are here to help them.

As a trainer with the JP Institute, I advocate an all–encompassing approach to patient care. This includes any technology that is beneficial to our patients: Ultrasonics, lasers, locally administered antibiotics, molecular and genetic testing, systemic antibiotics when appropriate (prescribed by the doctor), nutritional analysis, Perioscope, three–dimensional imaging when available, specialist referral, and more.

There has never been a more exciting time to be in dentistry, and the future projects a myriad of treatment possibilities. Let's look to that future and reexamine what we do today. Fear of change is an obstacle that prevents us from achieving our full potential. Let's be bold and strive to use a fresh approach every day. Change is good!

Liz Lundry, RDH, is a senior consultant and laser trainer for the JP Institute. She provides in–office training, facilitates workshops, and is a national speaker and author. She is also a facilitator for the JP Institute's Hygiene Mastership Certification Program. Liz has been laser certified since 2000. She currently works in a practice that specializes in cosmetic and neuromuscular dentistry in San Ramon, CA. Liz will also be a presenter at the 2010 RDH Under One Roof conference in August 2010. For more information about the JP Institute's programs, visit www.jpconsultants.com or call (800) 946–4944.

References

- www.laserdentistry.org (Web site for Academy of Laser Dentistry)

- Coluzzi D, Dentistry Today. 2007 April;124–127

- Andrian E, et al. J Dent Res. 2006 May;85(5):392–404

- Brozovic S, et al. Microbiology. 2006 Mar; 152 (Pt 3):797–806

- Andreas M, et al. Lasers in Surgery and Medicine 1998; 22:302–311

- Pick R, Dentistry Today. 2000 Sept;50–53

- Wilkins E. Clinical Practice of the Dental Hygienist. 2004, 9th Ed.