An American Dental Hygienist in Ecuador

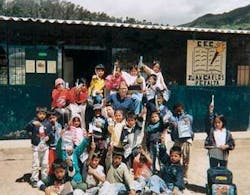

Upon my graduation from the baccalaureate program in dental hygiene at Northern Arizona University (Flagstaff, Ariz.), I had the good fortune to meet Lorena Teran, Doctor of Preventive Medicine and a graduate of the University of Southern California Medical School. Since 2003, Dr. Teran has headed a volunteer program in Ecuador that targets the children at Casa Hogar (a girls’ home), and has implemented an effective after-school program for the students of Juan Carlos Peralta Elementary School. The nonprofit program provides educational instruction by volunteer teachers, meals for the children (meals are seldom provided in school settings in Ecuador), and supports infrastructural repairs to the school (including paint, desks, and running water for showers).

While I had always been confident that my professional career would involve the private practice of dental hygiene in either Arizona or California, Dr. Teran invited me to spend some time as a volunteer dental hygienist on her preventive health-care team in Ecuador. Her project - “To Give Hope” - is privately funded by individual donations and has been ongoing for several years. Until my participation, starting in 2005, the project had been limited to public health medicine for children in relatively remote villages in the mountains north of Quito, the nation’s capital. No dental hygienist or dentist had ever participated previously. It didn’t take me very long to say an enthusiastic “yes!” Of course, at that time, I had no idea about the chain of events that my “yes” would set into motion.

Background

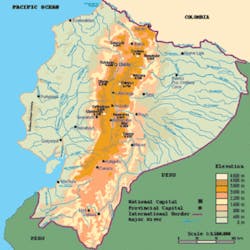

Ecuador, with a population of 13.3 million, is a small country (about the size of Nevada) in equatorial South America, bordered on the north by Colombia, on the south by Peru, on the east by the Amazon Basin, and on the west by a 2,000-mile Pacific coastline. Although it has been governed by an elected civilian government for 25 years, the nation’s history is one of continued political instability. For example, on average, every two years a new civilian or military government has taken control. Ecuador has had seven different presidents since 1996.

Economically, Ecuador is categorized as a “developing nation.” Unlike so many other small countries, Ecuador enjoys significant petroleum reserves, which provide more than 40 percent of the nation’s export earnings. Unfortunately, the fruits of this oil bounty are astoundingly unequally divided among the population. The richest 10 percent of the population control 32 percent of the financial wherewithal. More than 65 percent of Ecuadorans live below the poverty line, the unemployment rate is above 11 percent, and 47 percent of the population is considered to be “underemployed.” More than 60 percent of the workforce is engaged in the “services” sector of the economy. The infant mortality rate is 24 per 1,000 live births; comparatively, according to a 2005 report, the infant mortality rate in the United States is 6.5 deaths per 1,000 births. Sixty-five percent of the population is “Mestizo” (mixed white and Amerindian), 95 percent are Catholic, and the literacy rate of 15-year-olds is a gratifying 92.5 percent. Because Ecuador is a significant transit country for the cocaine trade from Colombia and for the laundering of drug-related monies, the crime rate is problematic, contributing also to the political instability.

Medical care availability is far below that in the United States. The physician-to-population ratio in Ecuador is 148 physicians per 100,000 inhabitants (U.S. = 550 per 100,000). Similarly, the dentist-to-population ratio is 17 dentists per 100,000 (U.S. = 60 per 100,000). Noteworthy also is that by far the great majority of physicians and dentists are situated in the country’s major population centers, leaving rural villages without readily available medical and dental care.

The profession of dental hygiene is virtually unknown in Ecuador. The major university in the capital city of Quito does not have a dental hygiene program, but a few dental hygienists are trained and educated at the much smaller Pontificia Universidad Catolica del Ecuador, also in Quito. As with physicians and dentists, practicing dental hygienists are found only in major population centers, primarily in Quito.

My volunteer dental hygiene project

In collaboration with Dr. Teran, and with assistance and guidance provided by my faculty mentor from the dental hygiene program at Northern Arizona University, it was decided that my project would be five-fold:

① Collection of baseline dental caries data from a cadre of 100 schoolchildren in a remote area of Santa Maria, Coto Collao, in the mountains north of Quito, a village that had no dental services of any kind

② Distribution of toothbrushes and dentifrices to the schoolchildren, and instruction in oral/dental hygiene

③ Placing occlusal fissure sealants in at-risk, noncarious teeth

④ Training the school teachers in the village to continue the oral hygiene efforts and to apply topical fluoride varnish, in anticipation of my return one year later

⑤ Arranging for referral of children with serious oral conditions for immediate and appropriate treatment in the dental clinics of the Ecuadoran Air Force.

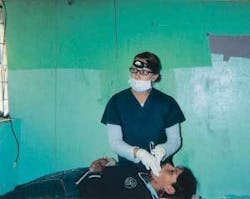

Materials and methods

Supplies for my project and financial support for travel were graciously provided by many individual and corporate donors (see Acknowledgments below). I used standard clinic charts to record carious lesions, from which I was subsequently able to calculate DMFT (see Results below). The only data collected were clinical (i.e., I did not have any radiographic equipment available). My clinical examinations were performed in the school rooms, using a portable dental unit and battery-powered lighting. Hand instruments were either disposable (plastic) or pre-sterilized (metal). Oral hygiene instruction was given classroom-style using charts, and because my Spanish is quite limited, a bilingual teacher provided enormous assistance. All of the children were eager, excited, and receptive to having a “foreigner” talk to them “about teeth”!

Patient population

During the four weeks on-site, I was able to examine 94 schoolchildren in the village. Of these, 55 were girls and 39 were boys. Almost all of them were traversing the “mixed dentition” stage. Interestingly, many of the children did not know how old they were because there are no official, governmental birth records in the village. I found that many of the children who were aware of their birthdate presented with developmentally delayed tooth eruption patterns relative to their ages, which could most likely be attributed to poor nutrition. The village water supply is a communal, centrally located well, with a few spigots systematically located throughout the village from which family members gather fresh water each day. The villagers routinely boil the water before consumption. I took a sample of that water and submitted it for analysis when I returned to Arizona. The sample showed only trace levels of fluoride. (Optimum water fluoride levels in the United States range from 0.7 to 1.2 ppm for maximum caries prevention.)

Results

The overall DMFT for the 94 schoolchildren was calculated as follows: D: 3.77, M: 0.46, F: 0.48, (Sealed: 1.4).

Total number of teeth: 2,272 (mean: 24.2 per child), broken down for females examined: D: 2.7, M: 0.5, F: 0.43.

Total number of teeth: 1,340 (mean: 24.4 per child), broken down for males examined: D: 4.9, M: 0.4, F: 0.54.

Total number of teeth: 932 (mean: 23.9).

It is important to point out that my DMFT scores derived only from clinical examination. I had no radiographic equipment at my disposal. If bitewing radiographs had been included in the DMFT calculations, the overall scores would most certainly have been much higher.

Discussion and conclusions

As a recent graduate from a highly regarded dental hygiene program, this “third world” experience was fascinating, and invaluable to my own growth in our profession. I look forward to returning to “my village” in the Ecuadoran mountains on an annual basis to follow up with the children I have already examined and treated. I am also exploring opportunities to expand the scope of my research and treatment endeavors to other Ecuadorans, even possibly to other villages. I was greeted warmly by everyone I met, and I sensed a genuine appreciation for my work in Ecuador. I will continue to work on my Spanish skills, because I am certain I could make an even more important contribution to oral health if I could converse more effectively. Neither Dr. Teran nor I encountered any resistance from Ecuadoran governmental officials or agencies; quite the contrary, our U.S. degrees and licenses were accepted and respected.

Dentistry and dental hygiene remain as unknown concepts in many developing nations. The opportunities for volunteerism are numerous. In terms of health care in Ecuador, for example, three prominent organizations welcome physicians, dentists, and hygienists:

● La Asociacion Vivir, www.asociacionvivir.com

● Hospital Baca Ortiz, www.nrcsa.com

● Donum Cuenca, www.ecuadorvolunteers.org

It is clear that DMFT data from developing nations will not parallel those of the United States or the industrialized countries of Western Europe and Scandinavia for many years or decades. But just a few dedicated volunteers can make a substantial impact. And the rewards in terms of personal satisfaction are beyond words! Please volunteer!

Author acknowledgments: Special thanks to Dr. Thomas Hassell for his guidance, encouragement, and continuing support of my project. Supplies were donated by Patterson Dental Company (Phoenix, Ariz.), Dentsply Dental (York, Pa.), the American Dental Association (Chicago, Ill.), Ultra-Dent Co. (South Jordan, Utah), and Oral-B Co. (South Boston, Mass.). Financial support was provided by Dr. Thomas Hassell (Flagstaff, Ariz.), Mr. and Mrs. John Starkey (Tempe, Ariz.), Dr. David Frausto (Prescott, Ariz.), Mr. and Mrs. John Behnke (Yorba Linda, Calif.), and Dr. Mark Costes (Flagstaff, Ariz.). My thanks to the Northern Arizona University Department of Dental Hygiene for loaning me the portable dental unit for this project.