The acceptance of change in dental diagnosis

Practicing dentists are not embracing digital radiography as quickly as hoped or predicted, but future use of the technology with new graduates will bring about a change in dentistry.

Why is the dental profession apparently resisting the move forward in a digital world? This question is addressed in the following exploratory study. As we begin the 21st century, the technological advances in dentistry have translated into dental procedures that are faster, more precise and patient-friendly, resulting in positive comprehensive dental evaluations and dental treatment decisions.

Recent developments include fiberoptic illuminators and laser instruments for early caries detection, air abrasion and hard-tissue lasers to remove decay, dental implant restorations, tooth whitening and bleaching techniques, and surgical lasers. The new technological advances challenge the dental practitioner in all aspects of dentistry.

Roentgen’s discovery of the X-ray revolutionized medicine and dentistry. This diagnostic tool made it possible to visualize structures of the human body. The introduction of a computer approach in radiography is once again revolutionizing the practice of dentistry. Digital imaging is the new wave.

As a clinical instructor in dental radiology, I have observed dentistry advance in the field of radiography. Digital imaging uses a sensor and computerized imaging system to produce a radiographic image on a monitor. This technique is a new application of digital technology that allows the dental professional to register dental images.

New technology involves change and conflict. The new information age has given rise to the dynamic exchange of information, access to information, and the individual’s right to privacy and ethical conduct regarding dissemination of information and censorship. As a result, dental programs across the United States have introduced digital radiography, and faculty and students are receptive, computer-literate, and ready to learn imaging software.

Nevertheless, practicing dentists are not embracing the new technology as quickly as hoped or predicted, but future use of digital radiography with new graduates will bring about a change in dentistry. The dental profession should work more closely with manufacturers to correct some of digital radiography’s imperfections. In so doing, the dental community will eventually accept change and resolve conflicts, and more dentists will practice digital radiography.

The responsibility of clinical instruction is to share enthusiasm and appreciation for learning. As a teacher, I strongly believe in exploring new technologies in the oral health care setting. Classroom instructors have demonstrated their desire to move forward by incorporating advanced techniques and skills. This promotes improved treatment for patients and gives dental practitioners more confidence treating the patient. It is the instructor’s responsibility to expose students to new methods and create a climate that fosters critical and creative thinking.

An instructor’s desire to engage students in learning and to find relevance in their daily lives can be integrated into larger areas of knowledge. Instructors are expected to be primary agents of change.

Dental auxiliary students are eager to learn new techniques. They don’t know the old ways and are open to new ideas. Today’s students are adept in digital techniques and want to use skills that are compatible with their schooling.

Digital radiography will eventually become the standard in dental practice. The acceptance regarding legal issues and high costs will occur only after the digital industry adapts, and after careful planning and implementation of universal standards. The American Dental Association can help by coordinating the standard of dental imaging. The indicators for change are in place, and dental records are moving toward digital practice.

I hope the study described by this article will spur others to determine the need for further investigation into digital radiography and/or related new technologies that will come to the forefront of dentistry in the future.

Harriet H. Kushins, CDA, RDH, MA, is an adjunct assistant professor at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, where she is currently teaching in the dental radiology department. She is also an adjunct faculty member at Bergen Community College in Paramus, N.J., teaching clinical practice.

The profession’s view of digital radiography

The questionnaire on which the study referred to in this article led to several conclusions:

❍ Studies reveal that digital and film-based radiography are comparable diagnostic tools. With the current state of the art, there may be no compelling reason to justify conversion to digital radiography. On the other hand, some observations demonstrate real advantages to making the conversion.

❍ Acceptance of digital radiography is slow, both in dental education programs and dental practices, because of the high cost of initial implementation, the poorly designed digital sensor that creates patient discomfort, and the lack of universal standard in technology.

❍ Many dental school programs purchase the equipment, then don’t use it rigorously. In many cases, instructors aren’t properly trained on the equipment. A negative attitude is created and the general opinion becomes, “Digital equipment is not worth the effort.”

❍ The attitude is more conservative in a few schools. If students correctly learn the principles of radiology, they can become proficient in any technique and learn the specifics on the job.

❍ Dental education programs are influential in the acceptance or resistance of change. If a school is prepared and instructors are trained, students will have the advantage of good instruction.

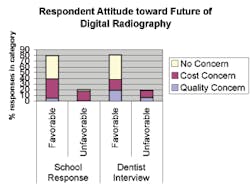

❍ Based on interview responses, digital imaging will be accepted into dental practices within 10 years.

Results of the questionnaire regarding attitudes in dental imaging radiology included:

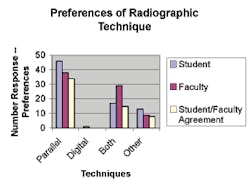

❏ The preferred method today is the film-based parallel technique used by both students and faculty. The attitude of faculty is important to the student because preference of teaching is guided by and dependent upon the instructor.

❏ The dental hygiene and dental assisting program directors are not fully aware of the technical and economic implications.

❏ The program directors feel that there is a future for the technology, but are waiting for further improvement and the cost to go down. The acceptance of change is dependent upon the educators’ and instructors’ views on this new technology.

❏ The size of the program and location of the school are determining factors. Results indicate that the cost of the equipment is too high in small programs, therefore the film-based technique is taught. In the rural and small industrial towns, the digital method is not taught.

❏ Students are trained both in didactic and laboratory instruction with competencies in digital and conventional radiographic techniques.

❏ Students are influenced by faculty instruction. The overwhelming preference by students is the film-based parallel technique and coincides where the faculty shows the same preference.

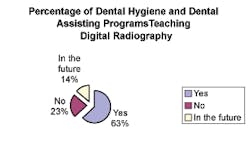

❏ Digital radiography is taught in 51 percent of schools. In less densely populated areas, digital is not taught. Dental practices are small and the technology is costly.

❏ Based on the reported demand for dental hygiene and dental assisting graduates with digital training, there is no disadvantage for the untrained graduate. Schools rarely receive requests for digitally trained clinicians.

❏ Approximately 80 percent (61 of the 76 respondents) of the schools indicated that digital radiography should be integrated into the curriculum. A significant indicator suggests faculty-recognized digital radiology is here to stay and will be the way of the future.

❏ Approximately 40 percent of the respondents were able to instruct in both didactic and laboratory methods. Thirty percent did not have an answer for this question, possibly due to indifference or they didn’t teach the digital method.

❏ Approximately 50 percent of faculty preferred the film-based technique compared to 38 percent of the faculty that equally accepted both techniques. It is surmised that faculty is not well trained in this technology. It may be due to lack of interest, little or no influence from their department, and/or lack of demand from the dental profession.

Editor’s note: The following information contains details about the study on the usage of digital radiography.

Abstract

Technology is rapidly advancing in all areas of society, and dentistry is no exception. Dental teams are becoming challenged to incorporate the technology, make the transition, and accept change as the number of technology choices increases frequently.

The purpose of this study is to determine attitudes regarding the use of digital radiographs. It attempts to define how different attitudes influence the change, and if modern techniques can create a technological evolution when used in conjunction with traditional methods. Is this new technology in dentistry being accepted and, if not, why?

The research consisted of 101 questionnaires sent to directors of dental hygiene programs. Seventy-six responded - more than anticipated. It was clear that this study indicated great interest and concern regarding acceptance and application of digital radiography, both clinically and in the classroom.

To compare attitudes, 16 dental practitioners were interviewed - one nonpracticing dental radiologist in teaching and research; seven practicing dentists in general practice; one practicing dentist offering care in a correctional institution; one practicing dentist in a cosmetic and periodontal general practice; one practicing dentist in orthodontics; and five postgraduate endodontist residents.

The third method of research was to review published studies. Studies conducted in the use of digital imaging and film-based conventional radiography revealed little difference in diagnostic information in periodontal disease, endodontics, or caries detection. The literature compares digital radiography with film-based radiography.

Method

The questionnaire was developed using a Likert Scale, which presents a set of attitude statements. The questionnaire was sent to colleges with entry-level dental hygiene programs in 23 states in the eastern and southern United States, and 26 schools with dental assisting programs.

The questions included:

• Digital technology is creating change in education, business, medical treatment and financial services. Is the change accepted in dental diagnostics? To what degree? Why or why not?

• Do the methods and/or approaches of teaching the digital technology affect the rate of change or acceptance?

• Are there other underlying reasons that affect the results?

• Does the technological change provide necessary health or economic benefits that will allow for the technology’s sustained use?

• If this technology in itself is not a strong driver, will it evoke further evolutionary change?

Dental interviews

The dentists overwhelmingly agreed that the digital age is here to stay. Fourteen of the 16 believe that in time, digital diagnostics will be the predominant tool. Digital radiography is more readily received in endodontics, where multiple images are required for root canal therapy, and minimal radiation is a major factor. The reduction in dose is approximately 50 to 90 percent in digital radiography (Haring, 392-393).

The attitude of dental practitioners is based on their length of time in practice and their specialization. The notion that this new technology is in a state of flux is an important factor versus the status of health and economic benefits. Dental professionals recognize that future generations of dentists will be using the new equipment, but want to see improvement in the cost and quality.

Published studies

Several studies conducted in the utilization of digital imaging and film-based conventional radiography revealed no significant difference in periodontal disease, endodontics, or caries detection.

• Study one: Comparing the diagnostic evaluation of peri-implant conditions both in direct digital and conventional intraoral techniques examined by 10 viewers in 50 pairs of radiographs resulted in no statistical differences (Morner, 1). The study also included patients’ experiences using both techniques (Morner, 2). Their opinions on the two different types indicated no statistical difference ( Morner, 2). The results concluded that digital radiography is equal to diagnostic assessment compared to film radiography in implants (Morner, 2).

• Study two: Root canal length measurement using digital (photostimulable storage phosphor system), [an indirect imaging system], and conventional radiography in 70 extracted human teeth with preserved roots indicated the following results: Accuracy in root-length measurement in the two systems was comparable. Except when length measurement was at size 15 file, the digital techniques proved better results. Conclusions drawn from the study is that conventional method using E-speed film is the technique of choice for root canal length measurement, excluding size 15 file, where the digital system appeared to have superior results (Lozano, 542).

The digital imaging in both studies were effective in reducing film processing time, magnification of digital images to highlight areas of concern in apical sites, and reduced ionizing radiation. When comparing both techniques in detecting small canals and small endodontic instruments, the conventional method was more accurate (Lozano, 543).

• Study three: The study involved 20 natural posterior extracted human teeth to determine the working length of the 20 root canals using the Schick Technologies CDR direct digital system and conventional film radiography using E-speed film (Lamus, 1). The results of the study indicate the following: There was less than a 1 mm statistical difference in length measurement with Schick versus conventional method. Clinical difference in this measurement was not considered significant (Lamus, 3). Conclusion: Both techniques are adequate. I would argue that further studies using the direct digital segmental measurement tool would be advisable.

References

1. Da Costa, Victoria. Digital X-Rays. RDH. (2003). 76+. http://www.rdhmag.com. 12 February 2004.

2. Dale, Miles A. Radiology in a Digital Age: No Escaping Reality. June 2002. http:www.learndigital.net. 23 May 2004.

3. Farman, Allan G. and Taeko T. Farman. Digital Intra-Oral Radiography. American Association of Dental Maxillofacial Radiographic Techniques [AADMRT Newsletter]. (Spring, 2002). 12 February 2004.

4. Florman, Michael, et.al. The Academy of Dental Therapeutics and Stomatology. (Spring, 2004). 1-7.

5. Haring, Joen I. and Laura Jansen. Dental Radiography: Principles and Techniques. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co., 2000: 384 -393.

6. Howerton, Laura J. Advancements in Radiology. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. (2003).

7. Lamus, Federico, et.al. Evaluation of a Digital Measurement Tool to Estimate Working Length in Endodontics. The Journal of Contemporary Dental Practice. 2.1 (2001): 1-5.

8. Lozano, A., L. Forner and C. Llena. In Vitro Comparison of Root-Canal Measurements with Conventional and Digital Radiography. International Endodontic Journal. 35.6 (2002): 542-550.

9. Morner-Svalling, Ann-Catherine. Comparison of the Diagnostic Potential of Direct Digital and Conventional Intraoral Radiology in the Evaluation of Peri-Implant Conditions. Clinical Oral Implants Research. 14.6 (2003): 714-719.

10. Parks, Edwin T. and Gail F. Williamson. Digital Radiography: An Overview. The Journal of Contemporary Practice. 3 (2002): 1-11.

11. White, Stuart and Michael J. Pharoah. Oral Radiology: Principles and Interpretation. St. Louis: Mosby, Inc., 2000: 223-227.