Lessons from global survey data: What else can dental hygienists do to close the periodontal disease prevention gap?

Periodontal disease threatens both the physical and fiscal health of society. Periodontitis, especially in its advanced stages, is the main cause of tooth loss among adults, and its economic burden has been estimated to be $154.06 billion in the US and €158.64 billion in Europe.1 Additionally, Scientific American has recently highlighted the association between poor periodontal health and systemic diseases including Alzheimer’s disease,2 colon cancer,2 rheumatoid arthritis,2,3 endocarditis,3 cardiovascular disease,4,5 and heart failure.3 The authors note that study data support a causal link between periodontitis and diabetes:5 periodontitis is associated with higher levels of glycated hemoglobin (a measure of average blood glucose),5,6 and among individuals with diabetes, periodontitis is associated with more severe diabetes complications.6

Preventive care is widely recognized as key in the fight against periodontal disease and its physical and economic sequelae, but until recent years it has been hard to put a price on prevention. To estimate the monetary cost, a 2021 cost-benefit analysis of treatment versus prevention across six European countries determined that eliminating gingivitis, the precursor to periodontitis, through improved home care would have a strong return on investment compared to the current approach.7 Moreover, a recent resolution of the 74th World Health Assembly affirmed the importance of a preventive approach to oral health, urging member states to focus more on health-centered prevention and less on pathology-driven treatment.8 Dental hygienists are in a unique position to respond to this call to prevention, which the Assembly addressed to “all stakeholders”8 in oral health.

Related reading:

Oral health-systemic disease survey

According to this survey,9 most dental hygienists are aware of the link between oral health and overall health; about 90% of respondents agreed that this link has been established for cardiovascular disease and diabetes. The oral health practice that respondents deemed most important to reduce the risk for systemic diseases was regular plaque removal via toothbrushing (91%). However, only 25% and 16% indicated a belief that controlling plaque regrowth with an antimicrobial toothpaste and rinse, respectively, is important for reducing the risk of systemic disease. The reality is that at-home toothbrushing, even by the most skilled patients, does not remove or disrupt all biofilm nor do patients spend long enough in doing so.12 Studies also show that antimicrobial toothpaste13 and rinse14 help control plaque beyond mechanical brushing, thereby reducing inflammation and bleeding, though some products and formulations outperform others. The best approach to control plaque and prevent plaque-associated diseases is to combine effective mechanical toothbrushing and an interdental cleaning method with clinically proven antimicrobial toothpaste and rinse.15

Toothpaste survey

Another survey looked more closely at respondents’ perception and recommendation of toothpastes.10 About 80% of respondents agreed that toothpaste playsElectric toothbrush survey

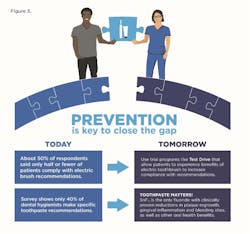

Two-thirds of respondents to the electric toothbrush survey agreed there is strong evidence showing superior plaque removal for electric toothbrushes over manual toothbrushes, and 96% of respondents often or sometimes recommend electric toothbrushes to their patients.11 However, about half of respondents reported that among their patients, 50% or fewer act on this recommendation. This data reveals an opportunity to seek solutions that increase patient adherence to professional recommendations. Respondents report that patients want more information about how electric toothbrushes compare to manual brushes (72%) and to other electric brushes (69%), suggesting that access to this information might increase patient compliance to the recommendation. Dental hygienists can share the powerful data that support the superiority of electric toothbrushes in general,17 and oscillating-rotating brushes in particular,18 for plaque removal and improved gingival health.

Practical implications

Looking at the survey results, we find some actionable data points to improve the oral health of our patients. Some of these data points may seem intuitive toThese improvements begin with education. The evidence points to the importance of prevention, meaning oral hygiene cannot be trivialized. Looking for opportunities and engaging with the wider health-care team can underscore our role in this with the medical profession. Equally significant is the opportunity we have in the dental office. From the referring dentist to practice managers to the reception staff, all should realize and emphasize the importance of the appointment time spent learning necessary oral hygiene skills. The hygiene appointment is not just for “teeth cleaning”—it is the key pillar to maintaining health. Oral hygiene advice should be the central focus of the appointment, and strategies to promote positive behavior change (e.g., motivational interviewing19) can be useful. We need the support of the entire dental team to reinforce this message.

As dental hygienists, it is in our patients’ best interests to stay abreast of the science. Evaluating the plaque control benefits of therapeutic adjuncts such as toothpaste and rinse, along with being informed about best practices in the home self-care regimen, is a responsibility of the dental hygiene profession. New technologies have constantly advanced therapeutic benefits over the years, but this isn’t always reflected in the undergraduate curriculum.

The next step is to educate our patients about effective products that fit their individual needs. The value of making patient-specific recommendations is recognized by experts,20 so we should make evidence-based suggestions that our patients will comply with and benefit from. The survey data reveals there’s an opportunity for dental hygienists to be more specific in their recommendations for antimicrobial toothpaste and rinse.9 While hygienists already overwhelmingly endorse electric toothbrushes, less than half think patients actually use them.

Ways to increase patient compliance

Any advice we give is beneficial only when patients comply, so how can we make our recommendations stick? There are many ways to increase the likelihood that patients will adopt the recommended procedures as part of their oral hygiene routine. Here are some simple steps to follow:

- Provide information in conversation. These messages can be reinforced via a prepared pamphlet or an instructional video/social media clip.

- Offer a product sample to make it easier for patients to evaluate the benefits of something unfamiliar.

- Show them how and when to use the sample to help ensure that patients get the best results.

- Use demonstration programs to allow patients to experience an electric toothbrush (think of a test drive) while in the dental chair. Along with brushing advice from the hygienist, this is a wonderful way to experience the correct brushing technique and feel of a brush.

- Use interactive apps with electric toothbrushes to reinforce proper brushing techniques at home.

- Ask patients when they could see themselves fitting what they’ve just learned into their routine.

Overcoming barriers

One of the key barriers to effective oral health advice is having a nonreceptive patient. Patients historically expect “treatment” when they have an appointment with the dental hygienist and normally don’t see the value in oral hygiene instruction. What could make a patient more receptive to spending time learning how to improve their oral health than new evidence showing it costs more not to do it? Or explain how the condition of the mouth has a relationship to whole-body health? Self-care performed every day is the least expensive route with the best long-term outcomes.21

By educating ourselves, our colleagues, and our patients about choosing—and properly using—the right preventive care products, we can continue to improve oral health and prevent disease. In turn, this will undoubtedly have a positive impact on overall health as well as the health and economy of the community. Together, we can close the gap.

Acknowledgment: The author wishes to thank Marisa DeNoble Loeffler, MS, for her assistance in preparing this article.

Editor's note: This article appeared in the March 2022 print edition of RDH magazine. Dental hygienists in North America are eligible for a complimentary print subscription. Sign up here.

References

- Botelho J, Machado V, Leira Y, Proença L, Chambrone L, Mendes JJ. Economic burden of periodontitis in the United States and Europe—an updated estimation. J Periodontol. Published online: May 30, 2021. 2021;10.1002/JPER.21-0111. doi:10.1002/JPER.21-0111

- Chronic gum disease may harm brain, joints, and gut. Sci Am. Accessed September 4, 2021. https://www.scientificamerican.com/custom-media/healthy-mouth-healthy-body/chronic-gum-disease-may-harm-brain-joints-and-gut/

- The surprising perils of periodontal disease. Sci Am. Accessed September 4, 2021. https://www.scientificamerican.com/custom-media/healthy-mouth-healthy-body/the-surprising-perils-of-periodontal-disease/

- A scientific approach to cleaning your mouth. Sci Am. Accessed September 4, 2021. https://www.scientificamerican.com/custom-media/a-scientific-approach-to-cleaning-your-mouth/

- How poor oral health fosters systemic disease. Sci Am. Accessed September 4, 2021. https://www.scientificamerican.com/custom-media/healthy-mouth-healthy-body/how-poor-oral-health-fosters-systemic-disease/

- Preshaw PM, Bissett SM. Periodontitis and diabetes. Br Dent J. 2019;227(7):577-584. doi:10.1038/s41415-019-0794-5

- Bishop C. Time to take gum disease seriously: the societal and economic impact of periodontitis. Economist Impact. Accessed August 30, 2021. https://eiuperspectives.economist.com/healthcare/time-take-gum-disease-seriously-societal-and-economic-impact-periodontitis

- Seventy-fourth World Health Assembly. Consolidated report by the director-general. A74/10 Rev.1. World Health Organization. April 26, 2021. Accessed August 30, 2021. https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA74/A74_10Rev1-en.pdf

- IFDH 2021 oral-systemic link survey. International Federation of Dental Hygienists. Accessed October 11, 2021. http://www.ifdh.org/ifdh-2021-oral-systemic-link-survey.html

- IFDH 2019 toothpaste survey. International Federation of Dental Hygienists. Accessed October 11, 2021. http://www.ifdh.org/ifdh-2019-toothpaste-survey.html

- IFDH 2020 electric toothbrush survey. International Federation of Dental Hygienists. Accessed October 11, 2021. http://www.ifdh.org/ifdh-2020-electric-toothbrush-survey.html

- Slot DE, Wiggelinkhuizen L, Rosema NAM, Van der Weijden GA. The efficacy of manual toothbrushes following a brushing exercise: a systematic review. Int J Dent Hyg. 2012;10(3):187-197. doi:10.1111/j.1601-5037.2012.00557.x

- Johannsen A, Emilson CG, Johannsen G, Konradsson K, Lingström P, Ramberg P. Effects of stabilized stannous fluoride dentifrice on dental calculus, dental plaque, gingivitis, halitosis and stain: a systematic review. Heliyon. 2019;5(12):e02850. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02850

- Albert-Kiszely A, Pjetursson BE, Salvi GE, et al. Comparison of the effects of cetylpyridinium chloride with an essential oil mouth rinse on dental plaque and gingivitis—a six-month randomized controlled clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34(8):658-667. doi:10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01103.x

- Kebschull M, Chapple I. Evidence-based, personalised and minimally invasive treatment for periodontitis patients—the new EFP S3-level clinical treatment guidelines. Br Dent J. 2020;229:443-449. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-020-2173-7

- Konradsson K, Lingström P, Emilson CG, Johannsen G, Ramberg P, Johannsen A. Stabilized stannous fluoride dentifrice in relation to dental caries, dental erosion and dentin hypersensitivity: a systematic review. Am J Dent. 2020;33(2):95-105.

- Pitchika V, Pink C, Völzke H, Welk A, Kocher T, Holtfreter B. Long-term impact of powered toothbrush on oral health: 11-year cohort study. J Clin Periodontol. 2019;46(7):713-722. doi:10.1111/jcpe.13126

- Grender J, Adam R, Zou Y. The effects of oscillating-rotating electric toothbrushes on plaque and gingival health: a meta-analysis. Am J Dent. 2020;33(1):3-11.

- Damatta M. Motivational interviewing in dentistry: a discussion worth having. RDH. December 17, 2019. Accessed November 18, 2021. https://www.rdhmag.com/patient-care/patient-education/article/14073753/motivational-interviewing-in-dentistry-a-discussion-worth-having

- Lively T. Personalize your OTC product recommendations for patients. Dental Products Report. December 1, 2020. Accessed October 11, 2021. https://www.dentalproductsreport.com/view/personalize-your-otc-product-recommendations-for-patients

- Watt RG, Daly B, Allison P, et al. Ending the neglect of global oral health: time for radical action. Lancet. 2019;394(10194):261-272. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31133-X

About the Author

Michaela ONeill, RDH, FAETC

Qualified from King’s College Hospital, London, as a dental hygienist, Michaela ONeill, RDH, FAETC, is a past president of the British Society of Dental Hygiene and Therapy (2014–2016) and is currently vice president of the International Federation of Dental Hygienists. She works for Procter & Gamble as a senior professional and scientific relations manager and corepresents the profession in changing UK legislation around the use of POMs by dental hygienists and therapists without the need of a prescription.

Updated March 2, 2022