Evidence-based dentistry: How research shapes better oral health decisions for patients and clinicians

What you'll learn in this article

- Evidence-based dentistry (EBDM) blends research, clinical expertise, and patient values for better outcomes.

- Qualitative vs. quantitative research: stories and experiences versus measurable data and predictions.

- Observational and experimental studies reveal patterns, risks, and cause-and-effect in oral health.

- Sampling methods like random and stratified ensure reliable, unbiased dental research.

- Valid research builds trust, guides patient decisions, and advances dentistry as a profession.

Dr. Alfred Fones developed a study on the impact the first class of dental hygienists had on school children at Bridgeport Public School in 1914.1 The data he collected studied the children’s mouths before and after hygiene treatment, and after that, dental hygiene education expanded.

In 1934, Dr. H. Trendley Dean showed organizational skills in collecting, sorting, and mapping data about the first findings regarding fluorosis.2 He developed the Community Fluorosis Index, which led to the discovery that fluoride in the water at the correct parts per million had a significant impact on lowering the prevalence of dental caries.2

Evidence-based decision making

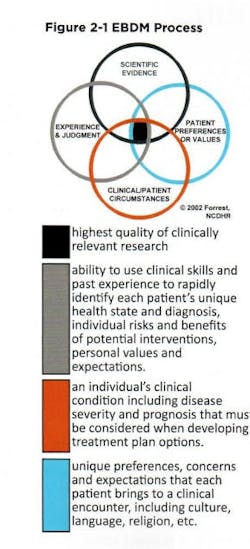

Evidence-based decision making (EBDM) is the process of identifying and interpreting results of the best scientific evidence.3 It’s about solving clinical problems using scientific findings in conjunction with the clinician’s experience and judgment, the patient’s values, and the clinical/patient circumstances (figure 1).

We can use EBDM when a patient refuses to use fluoride because they believe it’s harmful. Clinicians can find relevant, clear, and valid online publications that support this evidence is false, and we can then manage the large amount of information patients are accessing. Being able to show patients good science-based information will enhance a practitioner’s credibility and build rapport with the patient, all while enhancing quality of care.3,4

The difference between qualitative or quantitative research

The goals of qualitative research include describing multiple realities, developing understanding, and testing ground theories through observation, open-ended interviewing, or reviewing documents.5 An example of qualitative research is starting an oral hygiene education program at a nursing home and surveying the population about theie perception of dental care, their current oral hygiene knowledge, and their attitudes about learning new oral hygiene skills.

The distinction between qualitative and quantitative research is using words (qualitative) versus numbers (quantitative). Goals of quantitative research include establishing facts, predicting future trends, showing relationships between variables, and testing theories.5 An example of this method is researching the systemic effects of periodontist treatment with type 2 diabetes.

Observational study design

Observational studies tend to be descriptive or analytical.4 Descriptive observational research attempts to identify and describe the research topic to quantify the disease status in a community. A familiar example is a case study in which one person is researched and findings are reported. These studies can be used to define characteristics of a population with a case series report. Case series reports specifically focus on the prevalence of a disease in a small group and can be useful in building knowledge and generating hypotheses.4,6

Two more examples of descriptive studies are correlation studies and historical studies. Correlation studies are exploratory and attempt to establish a link between two variables, such as periodontal disease and obesity.3 Historical approaches use past events and records that can lead to new insights and recommendations.

Analytical studies determine the etiology of a disease and quantify the association between exposure and outcome. Examples are case-control studies, cohort studies, ecological studies, and cross-sectional studies.4

Case-control studies are retrospective (they work backward) and follow two groups of people: those with a condition called the cases and people without that condition.3 These studies allow researchers to explore associations between potential risk factors and various health conditions. A case-control study demonstrated a link between carcinoma of the lung and smoking tobacco.

Cohort studies and longitudinal ecological studies measure one group of individuals (the cohort) over time and record information multiple times to determine risks. These studies offer a long-term look at a person’s health and observe the incidence of a disease. By tracking individuals over time, factors that contribute to the development of caries, periodontal disease, or oral cancer, can be pinpointed. These include socioeconomic status, dietary habits, or early childhood experiences.

Experimental studies

Experimental studies, also known as clinical trials, use independent and dependent variables to provide the highest level of evidence of all the study designs.4 These studies are the highest level of scientific evidence and demonstrate cause and effect.3

Independent variables represent the factor being manipulated by the researchers. The dependent variables depend on changes in the independent variable. If there’s a study to determine whether using different polishing agents to see which one is most effective at removing biofilm, the independent variable being manipulated would be the polishing agent and the dependent variable would be the biofilm. In these studies, the researcher wants to find new effects of treatment in a controlled setting like a lab or clinic.

Key sampling techniques

The purpose of sampling is to allow the researcher to observe the entire population and add more weight to findings.5 Due to limited resources, time, and money, it’s not always feasible to obtain answers from all participants. The samples represent the total population so that the data collected from the samples will be as accurate as that population.

A random sample is formulated so that each person in the population has the same chance of being included.5 An example is a group of patients use a different dentifrice to treat dental hypersensitivity and to follow up with the first 20 who return for an interview about the product. This is not predictable and there is no bias.

Stratified random sampling is dividing a population into subgroups or strata and then randomly selecting from within.6 An example is dividing a large population into women and men and then choosing three from each group. Systematic random sampling involves selecting every Nth member. A simple example is if coworkers are lined up and every fourth person is chosen to create a population.4,6

Conclusion

Valid research is the foundation for understanding why disease occurs and how to prevent and control diseases. Being able to critically think can help clinicians predict which outcomes a patient can expect following procedures, choose the best products, and help patients navigate all the information available on the internet, all while guiding efforts to advance the profession.

References

1. Boyd LD, Mallonee LF. Wilkins’ Clinical Practice of the Dental Hygienist, 14th edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2024.

2. Beatty C. Community Oral Health Practice for the Dental Hygienist, 4th edition. Elsevier; 2017.

3. Rubinson L, Neutens J. Research Techniques for the Health Sciences, 3rd edition. Benjamin Cummings; 2002.

4. Nathe C. Dental Public Health and Research, 4th edition. Pearson; 2017.

5. Creswell J, Creswell JD. Research Design Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 6th edition. SAGE; 2023.

6. Forrest J, Miller S. EBDM in Action: Developing Competence in EB Practice, 3rd edition. JL Forest and SL Miller; 2022.

About the Author

Ashley Dudgeon Millon, MSHCM, RDH

Ashley, Assistant Professor of Comprehensive Dentistry at Louisiana State University Health Science Center, has been a practicing clinical dental hygienists for 13 years. She received a Bachelor of Science degree from LSUHSC in 2012 and Master of Healthcare Management from University of New Orleans in 2017. Her current interests are oral hygiene instructions, community outreach, and dental public health.