Petechiae, ecchymoses, or purpura?

by Nancy W. Burkhart, RDH, EdD

[email protected]

Your patient today is a 27-year-old male, Adam, who is a graduate student at the local university. He takes no medications, considers himself healthy, and exercises daily. Your exam is negative with healthy tissue, and no periodontal disease.

The only findings that you note are three small lesions of varying sizes opposite teeth #4 and #5. The areas are flat, non-ulcerated, red, and circumscribed. (see Figure 1). You show the patient the area in his mouth using a hand mirror and ask him if he has any idea why the lesions might have occurred. The patient responds that he does not know what might have affected these three areas.

You suggest that he may have eaten something such as a hard substance and caused trauma. After thinking for a moment, he tells you that he did eat a lot of chips at a Super Bowl party two days ago. Although he does not report any discomfort, the trauma theory is probably the most logical, educated assumption for these lesions in this case. This is especially true since his health history is negative and the areas of concern are isolated to one area of the mouth.

An intraoral slide of the area is always an excellent idea for future comparison, as well as having the patient view the area in a few days to be sure the lesions disappear. The patient is also instructed to come back to you, if the lesion is not completely unnoticeable in one week. A notation is made in your progress notes to check this area at his six-month recall. You also keep a list of patients that you follow up with phone calls and make a point to call him as well.

Etiology: Clinicians are often confused on whether to call an obvious red lesion — usually in the palatal area of the mouth — a petechiae, an ecchymoses, or a purpura. These lesions may have various etiologies, but most are due to trauma. With that said, it is sometimes easy to just classify these lesions as traumatic, missing some other key problems that may exist.

All three classifications are caused by hemorrhages in the tissues resulting from trauma, systemic disease, or blood dyscrasias. Blood dyscrasias are usually because of clotting factors or because of fewer platelets or a combination of these problems.

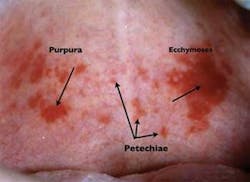

Distinguishing characteristics:

- Petechiae are small, usually rounded red or purple spots that are approximately 1-2 mm in size.

- Pupura are larger than the petechiae, but less than 1 cm in size. The shape depends upon the location of the tissue, and the amount/disbursement of the pooled blood.

- Ecchymoses is described as hemorrhagic spots that measure over 1 cm in size. Both purpura and ecchymoses may be irregular in shape depending upon the amount of pooled blood.

Perioral and intraoral characteristics: The size of each of the three clinical descriptions may vary and may be seen in one patient who exhibits all three classifications (see Figure 2). Because the lesion is caused by hemorrhages (pooled blood) within the tissues, the lesions will not blanch when diascopy is applied (diascopy is using a glass slide to apply pressure to the area of concern). If the flow of blood is disrupted, a vascular type lesion would be considered in a differential diagnosis. If the area of concern is in a difficult location where diascopy would not work, simply using the mirror to disrupt blood flow may be used.

Differential diagnosis: Whenever a noted lesion is discovered in the mouth or on the skin, a diagnosis must be made either by resolution or by biopsy for a definitive diagnosis. When petechiae, purpura, or ecchymoses are noted, some diseases and disorders should immediately be placed into a differential diagnosis. Depending upon the location and size of the lesions, certain etiology may apply.

- Trauma — Carefully questioning the patient about eating rough, coarse food, or traumatizing the area with blunt force. They may be using an object or finger to induce vomiting, as in the case of an eating disorder such as bulimia. Blood vessles may be broken due to the force of vomiting along with the trauma.

- Fellatio — Ask the patient if this could be true for them when suspected. The lesions usually have more of a purpura or ecchymoses appearance.

- Chewing on pencils, objects such as long-tail combs, toothbrushes, etc. The above mentioned objects are often utilized by patients with eating disorders to induce vomiting as well.

- Ill-fitting dentures or partial appliances that have caused trauma.

- Faulty restorations that are jagged or rough.

- Self-induced injuries may be considered as well. Patients who have psychological problems that promote self-inflicted injury.

- Blood disorders and dyscrasias — Usually fall under the petechiae category and blood and platelet abnormalities, hemorrhic diseases, and/or mucusal diseases related to systemic disorders may be considered.

- Lupus — Checking the exposed skin surfaces for any lesions that may be visible is appropriate. Evaluating the remaining oral tissues for any type of ulceration and erythema is warranted. The palate is a common area for oral lupus lesions and especially in the early stages of the disease. The lesions usually appear as a purpura or ecchymoses and not a petechiae (see Figure 3).

- Pemphigus vulgaris — Skin lesions are prominent in pemphigus vulgaris as well. Questioning the patient regarding family history and periodic skin or oral lesions is also warranted.

- Lichen planus — Evaluating the patient for any skin lesions that appear as purple, polygonal papules on flexor surfaces is appropriate. Lichen planus may appear as flat, red oral lesions and may be ulcerated as well when found orally. Questioning the patient about any lesions noticed in the past is appropriate.

- Lichenoid reactions — These lesions (see Figure 4) appear similar to lichen planus orally, but are caused by contact with dental materials, dental products, or by medications that the patient may be using or taking systemically. The appearance can be both clinically and microscopically similar. Discontinuing the product, removing the material, or changing to a different medication when possible is usually the best course of action.

Dental implications: The patient may be totally unaware of the lesion, but depending upon any discomfort, the patient may also be in your office to have the area evaluated. As we know, many disease states appear orally in the early stages of the disorder. The dentist and hygienist may be first professionals to evaluate these lesions and assist the patient in resolution or treatment.

Areas of trauma may be chronic in nature and the patient should be advised that constant irritation or inflammation anywhere in the body is detrimental and must be resolved. In the case of fellatio, the patient should be advised about safe-sex practices and the association with HPV 16 and oral cancer. Extensive information on the subject is available at the Oral Cancer Foundation (www.oralcancerfoundation.org/hpv).

Treatment and prognosis: Referring the patient to the correct healthcare provider is crucial in the case of suspected systemic diseases such as blood dyscrasias. Removing devices that are causing the trauma and rechecking the patient to make sure the lesions have resolved is necessary. Showing the patient the area and asking them to check the lesions is optimal. Depending upon whether the lesion is induced through trauma or whether it is systemic, the prognosis will vary.

It is rare to find dental offices that follow up with phone calls to check on patients who have lesions that should be watched until resolution.

A list should be kept, and patients should be contacted if there is an area of concern. Patients will forget or will not see the importance of re-evaluation without reminders in many cases.

References

Delong L, Burkhart N. General and Oral Pathology for The Dental Hygienists. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2008, Baltimore.

Pickett FA, Teerezhalmy GT. Dental Drug Reference with Clinical Implications. LWW:Baltimore, 2nd edition 2009.

Siegel MA, Kahn MA, Palazzolo MJ. Oral Cancer: a prosthodontic diagnosis. J Prosth Jan 18(1) 2009. 3-10

Yu T, Wood RE, Tenebaum HC. Delays in diagnosis of head and neck cancers. JCDA.74:1, February 2008.