Oral hairy leukoplakia

by Nancy W. Burkhart, RDH, EdD

[email protected]

Your patient today is Richard Ellis, who is a new patient that has not visited a dental practice for several years. His history is complicated since he is under treatment for AIDS and high blood pressure. Richard is a social drinker, occasionally uses recreational drugs, and is a long-term smoker. His physician has suggested that he maintain regular dental visits.

As you begin your exam of Richard's tongue, you notice that he has plaque and white lines that have a shaggy appearance on the lateral borders of the tongue (see Figure 1). Richard has noticed the white appearance and tells you that he has tried to brush the plaque away without success. With Richard's health history and a biopsy, it is determined that he has oral hairy leukoplakia.

Etiology: Hairy leukoplakia (HL) is caused by an infection with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), a member of the herpesvirus family. HL is secondary to immunosuppression of an individual, and is strongly linked to the immunosuppression that results from infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Any disease state that causes suppression of the immune function may place the patient at risk for development of HL.

Hairy leukoplakia was originally described in the early 1980s, and its appearance has actually decreased in relation to HIV since that time, as most patients are diagnosed and placed on antiviral therapy early during the disease. Hairy leukoplakia is more often associated with individuals who have low CD4+ cell counts, smokers, those using antifungal medications, and recreational drugs.

Epidemiology: As stated previously, HL occurs predominantly in those patients who are infected with the HIV virus. Other immune depressed states such as bone marrow transplant patients, organ transplant patients, or those using medications designed to depress the immune system, may also cause the patient to exhibit HL. Additionally, systemic diseases such as lymphocytic leukemia, multiple myeloma, and autoimmune diseases that are being treated with steroid therapy may exhibit HL as well.

Perioral and intraoral characteristics: HL is asymptomatic unless there is a candida infection in conjunction with HL, causing the characteristic burning sensation associated with candidiasis. The hygienist or dentist may be the first individual to notice the clinical signs related to suppressed immune function. The nonpainful, white, and corrugated/shaggy plaque appear as accentuated folds on the lateral borders of the tongue and are very characteristic of HL. The lesions are usually bilateral, but may be unilateral as well (see Figure 2).

Distingishing characteristics: The plaque does not wipe off with gauze. There is no bleeding or raw surface that is sometimes found with candida when wiped with gauze. However, candida may occur in conjunction with HL (see Figure 3).

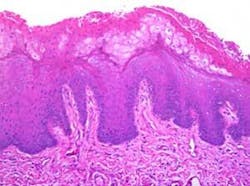

Significant microscopic characteristics: Microscopic appearances include hyperkeratosis with exophytic extensions of keratin that appear somewhat like hair. Many of the superficial keratinocytes show cytoplasmic clearing with perinuclear beading. Candida is often found on the surface of the specimen (see Figure 4).

Dental implications: The significance of HL is an important factor for the dental clinician since there is a progression in the case of HIV infection from HIV-latent infection to full-blown AIDS.

Differential diagnosis: Considerations may include lichen planus, frictional keratosis, candidiasis, thermal and chemical burns, migratory glossitis, tobacco use resulting in leukoplakia, squamous cell carcinoma, HPV, and lesions associated with syphilis.

Treatment and prognosis: In the case of HIV infection, antiretroviral therapy often produces improvement or resolution of the lesions; however, recurrence is not uncommon.

Acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir are often used in initial treatment. Topical applications of podophyllin resin and combinations of podophyllin with acyclovir are reported with good results. Candida may be found to be problematic and antifungal treatment may be needed as well.

There is no evidence that hairy leukoplakia has the potential for malignant transformation. However, a definitive diagnosis is needed since the lateral borders of the tongue are a high-risk area for oral cancer and also because HL may be an early sign of HIV infection. The gold standard of scalpel biopsy is the definitive diagnosis.

Additionally, baseline digital slides are beneficial to assess subtle changes in any lesion and additional slides as a follow-up procedure. Adjunct techniques such as exfoliative cytology using the brush biopsy and vital staining with toluidine blue help to supplement the clinical judgment of the practitioner. Careful, long-term monitoring of the patient is suggested with the above techniques and tissue biopsy when warranted by the clinician. Smoking cessation should be strongly encouraged for the patient.

References

Cawson RA, Odell EW. Essentials of Oral Pathology and Oral Medicine. 6th ed. Churchhill Livingstone, London. 1998.

Delong L, Burkhart NW. General and Oral Pathology for the Dental Hygienist. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore. 2007.

Eisen D, Lynch DP. The Mouth: Diagnosis and Treatment. Mosby, St. Louis. 1998.

Lee KH, Polonowita AD. Oral hairy leukoplakia arising in an oral lichen planus lesion in an otherwise immune-competent patient. N Z Dent J. 2007 Sep; 103(3): 58-9.

Mendoza N, Diamantis M, Arora A, Bartlett B, Gewirtzman A, Tremaine AM, Tyring S. Mucocutaneous manifestations of Epstein-Barr virus infection. Am J Clin Dermatol 2008; 9(5): 295-305.

Moura MD, Guimaraes TR, Fonseca LM, de Almeida Pordeus I, Mesquita RA. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2007 Jan: 103 (1):65-71. Epub 2006 June 6.

Nokta M. Oral manifestations associated with HIV infection. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2008 Feb; 5(1). Review.

Plemons J, Benton E, Rankin KV. Oral Hairy Leukoplakia: A case report. Texas Dental J. 2007 April Vol. XI. 5-7.

Regezi JA, Sciubba JJ, Jordan RCK. Oral Pathology: Clinical Pathologic Correlations. 4th ed. Saunders, St. Louis. 2003.

Shulman JD, Carpenter WM. Prevalence and risk factors associated with geographic tongue among US adults. Oral Disease 2006 Jul;12(4): 381-6.

Sroussi HY, Villines D, Epstein J, Alves MC, Alves ME. Oral lesions in HIV-positive dental patients — one more reason for tobacco smoking cessation. Oral Disease 2007 May;13(2) 324-8.