Squamous cell carcinoma

by Nancy W. Burkhart, RDH, EdD

[email protected]

Case study: Your patient today is a 47–year–old female, Rose, who has been a patient of record with your office for the past 10 years. Rose is currently taking alprazolam (Xanax) for anxiety, and atorvastatin (Lipitor) for high cholesterol. She reports taking an 80 mg low dose aspirin daily, a multivitamin, calcium, omega 3, and occasionally uses antacids.

She is a former smoker who stopped smoking about 10 years ago and consumes approximately four to five drinks of alcohol weekly. Rose has not been to your office for 28 months and has not been seen by anyone else due to her business schedule and travels.

Oral examination: As you begin your intraoral exam, you notice that the gingival tissue is dark pink and appears ulcerated at the margins, especially around tooth Nos. 9–13 (see Figure 1). Rose tells you that this area is of concern to her and that this fact is really why she scheduled the appointment with you today. She is unhappy with the appearance of her teeth, and is worried about the bleeding that she has noticed during the past several months.

As you assess the tissue, you refer to the previous radiographs and digital slides from several years ago. You see a noticeable difference. The tissue today appears bulbous, spongy, ulcerative, and has much more recession than noted previously. As you probe the area, there is spontaneous bleeding. You report your findings to the dentist, and he requests a biopsy of the gingival tissue, referring her to an oral surgeon. Several days later, the pathology report indicates a diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma of the gingiva.

Diagnosis: Squamous cell carcinoma of the gingiva

Etiology: The etiology of any type of cancer is multifaceted, including lifestyle choices, environmental influences, genetic factors, chronic infections and irritations, and viruses. Related factors such as sunlight, tobacco, alcohol, diet, stress, and chemical exposures from common products have been documented. A higher rate of cancer may be found in association with some long–term or chronic mucosal diseases such as lichen planus, oral submucous fibrosis, or other diseases with a high degree of inflammation. Inflammation affects all areas of the body at a cellular level.

Epidemiology: Squamous cell carcinoma encompasses at least 90% of all oral malignancies. Oral and pharyngeal cancers account for approximately 3% of all cancers in the United States. Men exceed women in developing this neoplasm by a 1.8 to 1 ratio.

Women continue to increase their risk of developing SCC orally probably because of increased life–style choices such as alcohol and tobacco use. There is evidence that the HPV virus 16 may play a role as well in oral cancer in both men and women, and oral sex is thought to be the mode of transmission associated with this virus. In addition, other HPV types 18, 33, and 35 have been implicated in many head and neck cancers.

Age and race are known factors in the development of oral cancers; however, oral cancer is being discovered in the 20 to 39 age group at a sixfold increased rate. This may be associated with the above mentioned factors. Increases in cancer of the tongue is being reported at an alarming rate. Cancer in younger individuals is usually a more aggressive type of cancer because of the stage at which it is usually discovered. Delay in cancer diagnoses has been documented, and it is an especially important contributor in the extent of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation that the patient may need to endure.

Perioral and intraoral characteristics: Squamous cell carcinoma of the gingiva may have a wide variety of clinical appearances. Many SCC lesions throughout the oral tissue exhibit erythroplakia, speckled erythroplakia, or a generalized ulcerative appearance. Additionally, the lesions may appear keratotic with some ulcerative characteristics without exhibiting a highly inflammatory appearance. Cancer may have many appearances, but most cases are nonhealing, rapidly growing, chronic type states with abnormal appearances. The patient cannot usually see the area on the oral tissues and may not be able to visually track the daily changes.

Distinguishing characteristics: Figure 1 suggests a later stage squamous cell carcinoma of the gingiva. Squamous cell carcinoma of the gingiva may appear very benign in its early stages. It is only after the tissue begins to change appearance and rapidly grow that suspicion usually begins to take place. Intraoral digital photographs are especially important in comparing subtle tissue changes.

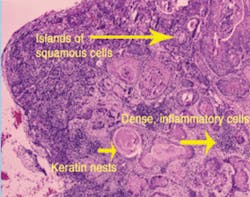

Significant microscopic features: Depending upon the stage of the cancer, cells will present with hyperchromatism, pleomorphism, increased nuclear cytoplasmic ratio, premature keratinzation, and formation of spheroidal masses of keratin deep within the epithelium. These nests are called keratin pearls. Mitosis is typically increased in numbers and often abnormal in appearance (see Figure 2).

Differential diagnosis: The case presented is of squamous cell carcinoma of the gingiva. Some mucosal diseases have inflammation as a core characteristic of the tissue. Any nonhealing, ulcerative tissue must have a confirmed diagnosis.

Scalpel biopsy is the gold standard. Any lesion that is questionable should have a diagnosis within a two week period or less. If a frictional component cannot be found, other more serious states need to be considered. With that said, the practitioner has the added responsibility of following the patient for any changes after the diagnosis and treatment phase. Oral cancer may recur and chronic inflammation of mucosal diseases enhance the chance of cellular or tissue changes.

Treatment and prognosis: The treatment for the patient is based on the stage of the cancer. Treatment will include surgical excision and may include chemotherapy, radiation, or a combination of these. Oral cancers of higher risk areas such as the floor of the mouth may need to be treated more aggressively, so the location is a factor as well. After treatment is completed, close follow–up for cancer in any area of the body must be carefully monitored with examinations.

Teaching all patients a self–exam technique for oral cancer detection is crucial, and this is especially important with any patient diagnosed with oral cancer. Assisting the patient in smoking cessation and elimination of alcohol products including mouth rinses containing alcohol should be mentioned.

Nutrition and lifestyle changes are important factors that are sometimes neglected in advising all patients on ways to maintain total health. Referrals to a nutritionist who is well–versed in oral cancer is especially important in assisting the patient in recovery. If radiation is part of the treatment, nutritionists are also helpful in making sure the patient is able to consume the desired nutrients during this phase while eating is especially painful. Lifestyle changes are equally important long–term, with stress reduction, exercise, healthful eating, and clinical assessments. With all our knowledge during the last decade, oral cancer is still undetected in an early stage most of the time. This is not acceptable.

Dental hygienists are in a prime position to discover early tissue changes and this should be one of our primary functions. Oral cancer is a cancer that is deforming, affecting speech, eating patterns, self–esteem, salivary function, and with all cancers, it is life–threatening. Please keep performing your extraoral and intraoral exams because what you do really matters.

References

- American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures. Available at http://www.cancer.org. (assessed on October 25th 2008).

- Liewellyn CD, Johnson NW, Warnakulasuriya S. Factors associated with delay in presentation among younger patients with oral cancer. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 2004:97:6, 707–713.

- Rhodus NL. Oral cancer: Early detection and prevention. Inside Dentistry, Jan 3:1, 2007.

- Schantz SP, Yu GP. Head and neck cancer incidence trends in young Americans. 1973–1997, with a special analysis for tongue cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head and Neck Surg. 2002;128(3);268–274.

- Warren–Morris D, Wade P. Oral cancer exams: Does your practice pass? Tex Dent J. 2006 June;123(6):494–9.

- Yu T, Wood RE, Tenenbaum HC. Delays in diagnosis of head and neck cancers. JCDA. 74:1, February 2008 http://www.cda–adc.ca/jcda/bol–74/issue–1/61.html.

- Pickett FA, Terezhalmy GT. Dental Drug Reference with Clinical Implications. LWW:Baltimore, 2nd edition. 2009.