So you want to be a volunteer?

Where and how to put together a program utilizing your skills

by Marilyn Cortell, RDH, MS, FAADH, and Maria Bilello, RDH, BSDH, MSPHIn this sagging economy, many of us feel grateful for what we have when so many others have less. We want to give back, but what do we give? If we can't write a check for every request that comes through the mail, what can we offer? Our time, talents, gifts, skills, and compassion, that's what. As dental hygienists we possess the skills necessary to be agents of change, and there's a vast population of undereducated, underserved, and underrepresented people who can feel the impact of our skills. As oral health educators, we have more to offer than we realize. The professional role of the dental hygienist includes serving and educating the public, and volunteering may be the vehicle for giving back.

Who volunteers?

"Volunteerism is the voluntary giving of time and talents, the direct delivery of service to others."1 According to the January 2010 report of the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics, both the number of volunteers and the volunteer rate rose from 2008 to 2009, as well as the rate of women volunteering, which increased from 29.4% to 30.1%.2

Most volunteers are not goody-goodies who want points for serving. They are simply passionate about who they serve and what they do, and they want to do it well. To this end, psychologists and sociologists study characteristics that may identify a typical volunteer, and one can note from the literature a variety of theoretical models that may be used to classify volunteers. Thoits and Hewitt of Vanderbilt University have listed five theoretical models:

The volunteer motivations model recognizes that individuals volunteer for very specific reasons, and although they perform the same work, their motivation and goals may be quite different. For example, individuals who volunteer may seek to develop social skills, enhance their self-esteem, or fulfill a need to be needed and appreciated.

The values and attitudes model focuses on the connection individuals make between volunteering and their belief systems. The desire to give back is part of their core values.

The role-identity model suggests that those who have volunteered before tend to make a more sustained volunteer commitment. A subclassification within this model is "group identity," which explains that those in a similar situation tend to provide help to others in the same situation. For example, if your child is disabled, it is likely that you will want to help in a center for the disabled.

The volunteer personality model refers to individuals whose personalities predispose them to specific traits that motivate volunteerism, such as a high level of confidence. Good coping skills also enable people to handle more challenging situations.

The personal well-being model, introduced by Thoits and Hewitt in their 2001 study, looks at the relationship between volunteers and the six aspects of personal well-being. The model demonstrates that happiness, life satisfaction, self-esteem, sense of control over life, physical health, and reduced depression are enhanced through volunteerism.3

Although volunteer work is widely believed to be beneficial to the community, invariably those who volunteer claim they get more out of it than they give. In the October 2010 issue of RDH, Linda Meeuwenberg, RDH, MA, stated that "Volunteering has been credited with improving the immune system, depression, self-esteem, and general well-being."4 Rosenberg and McCullough's 1981 study supports Meeuwenberg's statement by demonstrating how an individual's need to be needed has an important positive effect on well-being.4 Volunteering, as an enhancement of general well-being, provides a sense of meaning and purpose in life that is also supported by Thoits' (1992) study.5

Practical Aspects of Volunteering

When committing to a volunteer position you need to be practical. Time commitments can vary widely, from a couple of hours a week to long-term involvements. Often you are responsible for covering your own expenses, such as commuting to and from a venue. Family such as children or elderly parents will be affected by a change in your schedule, and their needs must be considered. One of the first steps when considering volunteering is to take a look at your obligations to see if you can come up with a time that you can comfortably manage. This will give you an idea of which volunteer opportunity might work for you.

Recently released data secured by the Corporation for National and Community Service entitled Volunteering in America 2010 states that "63.4 million Americans volunteered to help their communities in 2009, an additional 1.6 million volunteers when compared to 2008, contributing 8.1 billion hours of service, which has an estimated dollar value of nearly $169 billion." This study also breaks down the country by states with the highest rates of volunteerism, and Utah, Iowa, Minnesota, Nebraska, and Alaska are the top five. The study also includes "Where People Volunteer," and identifies specific areas of focus. Note that 8.3% of volunteers chose health as their area of focus.6

Where should I volunteer?

The underserved, undereducated, and underrepresented cover a vast range of people from all walks of life who, for whatever reason, have never learned about oral hygiene, and they have not been told about the important connection between oral health and systemic health. So, should you want to volunteer and use your dental hygiene knowledge and skills, you may find some workshops, lectures, and simple teaching sessions to be helpful and applicable for a diverse audience. Also, consider collaboration and volunteering with colleagues to develop a community outreach effort, one that benefits the underserved while enhancing the public image of dental hygiene, dentistry, and your specific dental practice.

• Kindergarten and public and private (corporate) day care – Many children do not know about oral hygiene – how important it is, how to brush their teeth, and once they learn, how to handle the situation if the rest of their family doesn't comply. You can be incredibly creative in helping children form a lifelong habit of maintaining optimum oral hygiene.

Another area of focus today is healthy eating and drinking. As dental hygiene students, we learned about sugars, retentive foods and drinks, and healthy snacking. Now, with an abundance of flavored milks and sugary energy/power drinks on the market, we can deliver valuable information relating to dental and general health for children, parents, caregivers, and the general public. Workshops can be set up with parent-teacher associations and preschools to educate parents and caregivers and reinforce what their children learned.

• Senior centers, residences, and nursing homes – Meeting the special needs of the growing population of seniors is paramount when considering health care today. Perhaps you know someone in one of these facilities, so it could be your opportunity to educate someone who did not grow up with oral health as a priority and who may never have heard of the oral-systemic connection.

Creativity is a wonderful adjunct to formal instruction and demonstrations. Marilyn Cortell began volunteering with her father while her mother was in a chronic care facility. They took Marilyn's standard poodle to a training program that would allow the dog to enter the facility and visit patients. Everyone marveled at how the dog knew exactly where to go when he got off the elevator no matter which side he exited. Marilyn taught staff how to manage the oral hygiene needs of their patients, including denture and prosthetic cleansing. Marilyn states, "I am convinced that while educating staff on behalf of their patients, the benefit was more far reaching in that the staff learned ways that oral hygiene can impact them and their families."

• Local hospitals, rehabilitation centers, and community outreach programs – Continuing education plays an extremely important role in hospitals across the U.S. Physicians, nurses, social workers, and other health-care professionals are required to stay abreast of the latest developments in their fields, as well as crossing over into other health care specialties. This is an opportunity to learn a topic of particular interest to you and speak about it in a professional setting. Another vehicle is to participate in lectures open to the public as a component of many hospital community outreach efforts. Contacting hospital community service departments may help you reach out to a broader community.

How do you begin to volunteer?

Begin by thinking about which groups you would be most comfortable working with, and with which groups you have established affiliations – young children, adolescents, parents, caregivers, senior citizens, physically or emotionally challenged, and others. The next step is to think about what kind of program you'd like to present and plan the program, much like creating a lesson plan. Developing this plan will help you format and organize the content appropriate for your audience. It will also serve as an outline when you submit a proposal to the program director stating what you would like to present.

Emphasis, no matter what venue you choose, will be placed on the three steps to achieve a healthy mouth: proper nutrition, brushing/flossing, and routine dental exams. An explanation of a healthy mouth, the etiology of a diseased mouth, and the role of plaque can be reinforced with pictures. You can demonstrate different toothbrushing methods and interdental cleaning devices, and provide participants with an opportunity to try out products.

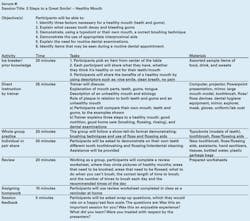

On this page, you will find a completed lesson plan (Sample #1) that was presented to a group of high functioning developmentally disabled adults as a part of New York City College of Technology's collaboration with HeartShare of New York. These adults were involved in a program whose goals were to train and transition individuals into independence. Oral hygiene instruction is an integral component of this program and can be adapted to a variety of audiences.

Putting it all together

What we have tried to do in this article is reinforce volunteering, understand what volunteer model fits your needs, and present options regarding where you may use your dental hygiene skills. The sample templates are guides to jump-start your thoughts, stimulate creativity, and produce a product that you care about. When you volunteer, whether it be dental hygiene related or a general community service, always mention that you are a dental hygienist with an extensive education that prepared you to recognize, manage, and prevent oral disease. This communication is imperative to reinforce the public image and respect for the profession of dental hygiene. Please know that when you volunteer, you contribute to the knowledge and health of others, while making a significant contribution to your personal health and well-being.

Maria Elena Bilello, RDH, MSPH, is currently a full-time assistant professor at New York City College of Technology in Brooklyn, N.Y., where she teaches oral histology and embryology, serves as the senior clinic coordinator, and has been recently named a Faculty Fellow working on a U.S. Department of Education Title V grant. Ms. Bilello has lectured in her area of expertise and educational domain on cultural sensitivity and continues research in the specialized areas of cultural sensitivity and oral cancer. She continues to practice as a clinical dental hygiene practitioner.

Marilyn Cortell, RDH, MS, FAADH, is a full-time associate professor at New York City College of Technology, Department of Dental Hygiene, where she teaches pharmacology and instructs in both senior and freshman clinic. As a dynamic and effective speaker, she is widely recognized for her expertise in oral health and its relation to total health. Credentialed as a Fellow in the American Academy of Dental Hygiene, a Consultant Member to the North East Regional Board of Dental Examiners, a member of the Advisory Panel of The Drug Information Handbook for Dentistry and actively serving on the Editorial Advisory Boards of Access and RDH, she has also contributed to three leading dental hygiene textbooks. Marilyn encourages volunteerism in both her academic community and within the community at large.

References

1. President's Task Force on Private Sector Initiatives. 1982. Volunteers: A Valuable Resource. Washington, DC

2. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Division of Labor Force Statistics, PSB Suite 4675, 2 Massachusetts Avenue, NE Washington, DC 20212-0001 http://www.bls.gov/news.release/volun.nr0.htm.

3. Thoits PA, Hewett LN, 2001. "Volunteer Work and Well-Being." Journal of Health and Social Behavior 42:115-131.

4. Rosenberg M, McCullough B. 1981. "Mattering: Inferred Significance and Mental Health among Adolescents." Research in Community and Mental Health 2:163-82.

5. Meeuwenberg, 2010. "Volunteering-Renewal, inspiration, insight," Adapted, RDH 30. Article adapted from articles written for Association of Dental Implant Auxiliaries Jan. 2009 and the Florida Dental Hygiene Association, June.

6. Thoits PA. 1992. "Identity Structures and Psychological Well-Being: Gender and Marital Status Comparisons." Social Psychology Quarterly 55:236-56.

Past RDH Issues