Ergonomic options for carpal tunnel syndrome in dental hygiene

Contributing authors:

Christina Calleros, MS, RDH

Justine Ponce, MS, RDH

Due to their repetitive motions, awkward postures, and physical strain, dental hygienists are highly susceptible to musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs), conditions or injuries that affect the bones, joints, muscles, and connective tissues.1 My first of two articles focused on ways to reduce risk for neck and back pain with research into different seating options, loupes, and ways to arrange an operatory ergonomically. Here I explore different options to reduce another common MSD, carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS).

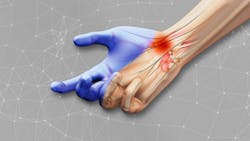

Carpal tunnel syndrome

CTS is a common MSD among dental hygienists, especially after they practices for 10 or more years.2 As defined by the Mayo Clinic, CTS results from injury or pressure on the median nerve that runs through the wrist. Symptoms include numbness, weakness, and pain in the thumb and fingers.3 A 2001 study found a 75% prevalence among 177 dental hygienists examined, and 56% showed classic CTS symptoms. Key causes in dental hygienists include excessive pinch force, repetitive movements of the hand and wrists, and unnatural hand positions.4

To reduce risk and prevalence, select ergonomic tools. There are three key areas where dental hygienists can make ergonomic improvements to prevent CTS—dental instruments, cordless polishers, and gloves.

Dental instruments

Dental instrument handle design is crucial in reducing MSD risk.5 A 2006 study examining muscle load usage and pinch force found that instruments with a diameter of 10 mm or greater and a weight of 15 g or less required less pinch force and muscle load than those with smaller diameters and heavier weights.6

Research has also shown that a balanced instrument, meaning the working end is centered along the handle’s axis, helps reduce pinch force by evenly distributing finger pressure. This allows the instrument to be more effective, efficient, and ergonomic.7 Based on this research, the ideal instrument is thicker in diameter, lightweight, and balanced.

Unlike manual scalers, which depend heavily on pinch force and lateral pressure (factors associated with MSDs), research has shown that mechanized instruments (ultrasonic scalers) employ power-driven mechanisms to efficiently remove calculus with less pinch force and muscle usage.8,9 Two common kinds of mechanized instruments are the magnetostrictive and piezoelectric scalers.

The magnetostrictive scalers transfer electrical energy to metal stacks to generate vibrations, while a piezoelectric scaler uses electrical energy to activate crystals for vibration. The key distinction for a clinician is that magnetostrictive scalers work on all sides, whereas piezoelectric scalers operate only on the lateral sides.9 Research has shown that ultrasonic scalers reduce treatment time, particularly for patients with heavy deposits, resulting in less muscle use and a lower ergonomic risk compared to manual scaling instruments.9

Cordless vs. corded polishers for RDHs

Most dental hygienists are familiar with corded handpieces/polishers. Corded handpieces are often heavy because of the added weight of the cord. This excess weight causes the dental hygienist to use a stronger pinch force to grasp the handpiece. The stronger the pinch force, the more chance of disorders such as CTS and tendonitis.6 Similar to magnifying loupes, there are no long-term studies on MSDs because of how new cordless polishers are.

Short-term studies have shown that a cordless polisher is significantly lighter and allows for a quicker polishing time because the cord is not in the way and is not weighing down the hand.10 This allows for less ergonomic risk because of the decreased pinch force and decreased overall usage.

Gloves for the dental operatory

Gloves are arguably one of the most frequently used instruments in a dental hygienists’ toolkit. A common mistake when choosing gloves is choosing either too small or too large. If a glove is too big, it can lead to a decrease in dexterity, clinical efficiency, and effectiveness. A glove that is too small can cause a loss of movement or flexibility and lead to muscle fatigue, which all increase the risk for MSDs.13 Correctly fitted gloves should fit loosely around the wrist with a snug, yet comfortable and nonrestrictive fit around the palm and fingers.11

Ambidextrous gloves are commonly used by dental hygienists because they’re less expensive than gloves designed for right-handed or left-handed use. Because ambidextrous gloves are designed to fit either hand, research has shown that the thumb portion of these gloves places the thumb in an unnatural position while also applying excess force to the thumb, which can contribute to muscle fatigue and hand pain.12

Glove thickness should also be considered. A 2009 study examining the effects of different glove attributes on grip force found that the thicker the glove material, the more effort required to complete the same task as those wearing no gloves.13 Another drawback to a thick glove was a greater loss of tactile sensitivity, which hygienists heavily rely on. One way to increase tactile sensitivity is to choose a glove with textured fingertips. This allows for a better grip, which permits less pinch force, especially in a wet environment like the mouth.13

Based on the research provided, balanced, thick-diameter and lightweight dental instruments, ultrasonic scalers, cordless polishers, and thin and textured tipped gloves are all tools that can decrease dental hygienists’ ergonomic risk for CTS.

Dental hygienists must prioritize their own health to sustain a long and fulfilling career. When their body suffers, their ability to provide satisfactory patient care also suffers. Choosing ergonomic, evidence-based equipment can help protect their future.

Sarah completed this article as a partial fulfillment for the Master of Science in Dental Hygiene from the University of New Mexico, Division of Dental Hygiene. Christina Calleros, MS, RDH, and Justine Ponce, MS, RDH, are faculty members with the University of New Mexico, Division of Dental Hygiene.

References

- Motaqi M, Ghanjal A. Musculoskeletal disorders: part 1. Tarbiat Modares Univ J System. 2019;4(1):127-131. https://ijmpp.modares.ac.ir/article-32-34610-en.html

- Lalumandier JA, McPhee SD. Prevalence and risk factors of hand problems and carpal tunnel syndrome among dental hygienists. J Dent Hyg. 2001;75(2):130-134.

- Carpal tunnel syndrome. Mayo Clinic. 2025. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/carpal-tunnel-syndrome/symptoms-causes/syc-20355603

- Abichandani S, Shaikh S, Nadiger R. Carpal tunnel syndrome - an occupational hazard facing dentistry. Int Dent J. 2013;63(5):230-6. doi:10.1111/idj.12037

- Suedbeck, J. Instrument design for optimal hand health. Dim Dent Hyg. March 29, 2024. https://dimensionsofdentalhygiene.com/article/instrument-design-for-optimal-hand-health/

- Dong H, Barr A, Loomer P, Laroche C, Young E, Rempel D. The effects of periodontal instrument handle design on hand muscle load and pinch force. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137(8):1123-1130. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0352

- Whiteley J. Hygiene instrumentation, hand health, and ergonomic harmony. RDH. April 20, 2022. https://www.rdhmag.com/ergonomics/instruments-handpieces/article/14186738/hygiene-instrumentation-hand-health-and-ergonomic-harmony-harmony-truefit-technology

- Chatterjee A, Baiju C, Bose S, Shetty S. Clinical uses and benefits of ultrasonic scalers as compared to curets: a review. J Oral Health Commun Dent. 2013;7(2):108-113. doi:10.5005/johcd-7-2-108

- Guignon A. Ultrasonics & ergonomics. RDH. January 1, 2010. https://www.rdhmag.com/career-profession/personal-wellness/article/16407808/ultrasonics-ergonomics

- Suedbeck J, Tolle S, McCombs G, Walker M, Russell D. Effects of instrument handle design on dental hygienists' forearm muscle activity during scaling. J Dent Hyg. 2017;91(3):46-54.

- Guignon A. What's happening to your hands? RDH. August 1, 2010. https://www.rdhmag.com/infection-control/water-safety/article/16407841/whats-happening-to-your-hands

- Powell BJ, Winkley GP, Brown JO, Etersque S. Evaluating the fit of ambidextrous and fitted gloves: implications for hand discomfort. J Am Dent Assoc. 1994;125(9):1235-1242. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.1994.0165

- Willms K, Wells R, Carnahan H. Glove attributes and their contribution to force decrement and increased effort in power grip. Hum Factors. 2009;51(6):797-812. doi:10.1177/0018720809357560

About the Author

Sarah Gilbert, BS, RDH

Sarah Gilbert, BS, RDH, lives in Connecticut and has three-plus years of clinical experience. She obtained her associate’s and bachelor's degrees from the University of Pittsburgh and is actively pursuing her Master’s in Dental Hygiene at the University of New Mexico, with an anticipated graduation date of May 2025. The continuing advancements in the profession motivate her passion for advanced education and ergonomics.