It’s now called ARONJ

by Lynne Slim, RDH, BSDH, MSDH

Sometimes we take our health for granted. I’m spending the day in the surgery waiting room of Gwinnett Medical Center, an upscale Atlanta hospital. My husband, David, is being prepped for spinal lumbar surgery. I’ll be here all day until he is transferred to a hospital room after surgery. While talking to everyone around me in the waiting room, I realize the fragility of our lives. It’s important that we take stock of life’s interruptions and focus on lessons learned.

As a columnist, one lesson I’ve learned in mentoring other dental hygienists is the need to handle the flood of information in dentistry and sort out the available evidence in an objective manner. Most dental hygienists have not been educated to do this (and neither have general dentists), and they fall prey to those who, for whatever reason, choose to present misinformation and half-truths.

I recently wrote a column titled “Jaw Dropping Update” about one of my favorite topics — bisphosphonate-induced osteonecrosis of the jaws. I focused on what I had read in a new book titled, “Oral and Intravenous Bisphosphonate-Induced Osteonecrosis of the Jaws” (second edition) by Dr. Robert Marx, chief of the division of oral and maxillofacial surgery at the University of Miami.1 For a nerdie weirdo like me, this book is a great sleeping companion! (Kidding, just kidding!)

In this month’s column, I’d like to refocus my attention on this topic and approach it a bit differently. Consultation with experts and textbooks are a great source of information but it’s also important to filter information from a variety of sources if you’re an evidence-based sleuth.

Sleuthing for evidence involves searching for the best evidence, and there’s a clear hierarchy that needs to be observed (in this order):

1. Evidence-based clinical guidelines (you can find some clinical guidelines in the Journal of the American Dental Association. An example can be found at jada.ada.org/content/141/5/509.full

2. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

3. Research studies (Notice that “studies” are at the bottom of the list. Studies, on their own, are often fraught with error, so don’t jump to any conclusions after reading a single study.) Most importantly, if speakers or writers reference their information with low-level single studies only, be suspicious!

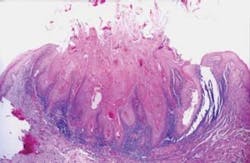

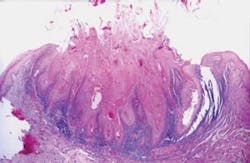

The first reported case of oral bisphosphonate-induced necrosis involved the administration of Fosamax and the subsequent failure of five fully integrated dental implants.2 In 2003, another case report surfaced and osteonecrosis was reported after intravenous administration of bisphosphonates during cancer treatment.2

Since then, a growing number of case reports and cohort studies have been published that have linked bisphosphonate therapy and osteonecrosis of the jaws (ONJ). In 2011, a case control study revealed that bisphosphonate use was strongly associated with ONJ for intravenous use and less so for oral use.3 Risk markers included local suppuration, dental extraction, and radiation therapy.3 When cancer patients were excluded, bisphosphonate use, suppuration, and extractions remained associated with ONJ.3 Higher risk of ONJ began within two years of bisphosphonate initiation and increased fourfold after two years for both IV and oral bisphosphonates. Suppuration and dental extractions were identified as independent risk factors for ONJ.3

I just finished reading a 2011 narrative review by the American Dental Association’s (ADA) Council on Scientific Affairs on the management of care delivered to patients who receive bisphosphonates for prevention and treatment of osteoporosis.4

The panel of experts reviewed the management of care for these patients and it’s a must print and read for all dental hygienists because it’s the most critical, objective evaluation of the scientific literature on this topic to date.

The use of the term “bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw” or BON/BRONJ has now been replaced by the term ARONJ which stands for “antiresorptive agent-induced ONJ.” According to the ADA, the reason for the change in terminology is because there are some non-bisphosphonate agents now available for treatment of women with postmenopausal osteoporosis and cancer patients that could also end up being associated with ONJ.4 Time and more research data will eventually tell the whole story.

Here’s a summary of the key points in this report:

- Antiresorptive therapy for low-bone mass places patients at low risk for developing ARONJ, and the highest prevalence estimate in a large sample is about 0.10%. The low risk of developing ARONJ can be minimized, but not eliminated.

- Discontinuing bisphosphonate therapy may not eliminate the risk of developing ARONJ.

- An ongoing oral health program consisting of evidence-based oral hygiene practices and regular dental care may be the best approach for lowering the risk of developing ARONJ.

- No validated diagnostic technique is currently available to determine which patients are at increased risk of developing ARONJ.

- Effective clinical practice involves many instances where critical information must be accurately communicated among all members of a patient’s health-care team. Get the patient’s medical care team involved in any decision that involves questions about or discontinuing bisphosphonate therapy.

References

1. Marx RE. (2011) Oral and Intravenous Bisphosphonate-Induced Osteonecrosis of the Jaws (2nd.ed.). Quintessence Publishing Co, Inc.

2. Pickett FA. Update on recommendations and issues for managing care of individuals with a history of taking oral bisphosphonates. Can J Dent Hygiene 2010; 44(1): 13-19.

3. Barasch A et al. Risk factors for osteonecrosis of the jaws: a case-control study from the CONDOR dental PBRN. J Dent Res. 2011 Apr; 90 (4): 439-444.

4. Hellstein JW. Managing the care of patients receiving antiresorptive therapy for prevention and treatment of osteoporosis: executive summary of recommendations from the American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. JADA 2011; 142(11): 1243-1251.

Past RDH Issues