Tonsilloliths are living biofilms

by Lynne H. Slim RDH, BSDH, MSDH

[email protected]

Yesterday was an odd clinical day for me. While in conversation with a patient, I let an expletive roll off my tongue. It was a four-letter word and it wasn’t a proud moment, but it’s something I’ve never done before and will never do again! What prompted the reaction was seeing something in the mouth that shocked the fool out of me.

Yesterday’s incident reminds me of the time when I had something else happen chairside. It was an experience I’ll never forget. A young, very attractive woman entered the operatory and, in typical Lynne Slim fashion, I began asking all the usual open-ended questions. When I asked her if there was anything in particular that was bothering her, she spoke up right away and said she was finding tiny, hard white balls near the base of her tongue. My initial thought was “Hmmm ... is this lady for real or is this just some wacko who just happened to land in my chair?”

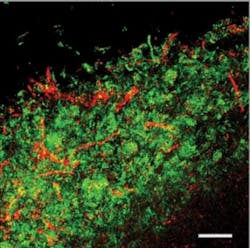

Microscopic image of a tonsillolith. The bacteria are stained red and green and make up large patches showing that the tonsillolith was crammed with bacteria.

I tend to believe just about everything my patients tell me, so I decided to take this assignment a little further.That night, I e-mailed the Listers’ chat group and asked whether or not anyone had ever heard this unusual complaint. Low and behold, my inbox was flooded with messages from fellow Listers, and I soon discovered that these tiny calcifications were not just stones but tonsilloliths!

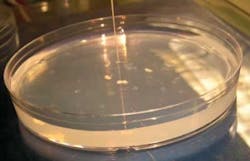

Some tonsilloliths placed on agar for testing. The "wire" sticking in one of them was the microelectrode which showed that they were anaerobic in the middle. Images done with support from Marko deJager and Marcelo Aspiras at Philips Oral Healthcare.

Bet you didn’t know that a tonsillolith is not just a stone but a living biofilm. Paul Stoodley, PhD, Center of Genomic Science, Allegheny-Singer Research Institute in Pittsburgh, sent me a published report about this topic.1

Most hygienists are familiar with dental biofilms. Those of us who are passionate about periodontal therapy are very knowledgeable about biofilm microniches in anaerobic pockets that can be occupied by anaerobic pathogens. Think of a microniche as another room in a house, like a damp, dark basement where creepie crawlies love to hide out.

One feature of the pharynx (another room in the house) that’s not much talked about are tonsilloliths. They act as localized concentrations of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria that calcify over time. Tonsilloliths progress from soft gels to hard “stones,” and are often associated with tonsillar inflammation. (Sound familiar, gingivitis fans?) These multicellular organisms are associated with halitosis and form within tonsillar crypts. The halitosis is thought to result from the release of volatile sulfur compounds produced from sulfur metabolism of anaerobic bacteria.1 In addition, tonsilloliths are associated with chronic cryptic tonsillitis, which often results in tonsillectomy.

Dr. Stoodley, now in the School of Engineering Sciences at Southampton University in the UK, Krespi, a Head and Neck surgeon based in New York city and deBeer, from the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology in Bremen, Germany, set out to determine the composition of tonsilloliths by using conventional thin section histology on 16 patients. Dr. Wenig, a senior surgical pathologist studied the specimens under a light microscope and, in addition, some tonsilloliths were selected for more in-depth analysis by confocal microscopy.

The thin histology sections and confocal imaging showed that tonsilloliths contain a high density of bacteria that are polymicrobial in nature and stratified (layered). The corncob structures and fusiform (tapered) morphology suggested to the researchers that F. nucleatum was in the mix and the images appeared similar to dental biofilms. F. nuleatum is an anaerobe that can produce volatile sulfur compounds. Some of the tonsillolith data showed that the bacteria inside the tonsilloliths were metabolically active and that oxygen consumption in the top layers depleted oxygen in deeper regions.

When the researchers added sucrose to the tonsillolith biofilms, oxygen was consumed and acid fermentation followed in a similar manner to that seen in dental biofilms. There was also a stratification of physiological activity within the tonsillolith biofilms with different types of activity at different levels. Keep in mind, however, that these biofilms were removed from host immunity and in what scientists call an ex-situ situation.

Fluoride was added to determine the influence on acid fermentation. The addition of fluoride reversed the pH drop caused by the addition of sucrose in the presence of 10% saliva. This response is considered similar to that observed in dental biofilms.

The next time you do an oral cancer screening exam, tell the patient you are also counting tonsilloliths (only kidding!). Based on what I’ve read, I’m already sharing the information with my patients, especially those with those nasty visible crypts.

References

1. Stoodley P et al. Tonsillolith: not just a stone but a living biofilm. Otolaryngology — Head and Neck Surgery 2009; 141:316-321. (This research was supported by a grant from Philips Oral Healthcare.)

Lynne Slim, RDH, BSDH, MSDH, is an award-winning writer who has published extensively in dental/dental hygiene journals. Lynne is the CEO of Perio C Dent, a dental practice management company that specializes in the incorporation of conservative periodontal therapy into the hygiene department of dental practices. Lynne is also the owner and moderator of the periotherapist yahoo group: www.yahoogroups.com/group/periotherapist. Lynne speaks on the topic of conservative periodontal therapy and other dental hygiene-related topics. She can be reached at [email protected] or www.periocdent.com.