BROOMS: Systematic screening for oral myofunctional disorders

Oral health extends far beyond just a brilliant smile or the absence of cavities. It encompasses a complex interplay of various factors that significantly impact a patient's overall well-being.

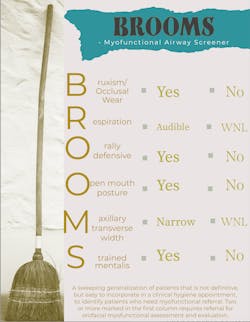

Among these factors, oral dysfunction stands as a crucial area of concern for dental professionals. Recognizing its profound implications for periodontal health, temporomandibular joint (TMJ) stability, orthodontic outcomes, and general oral health, the BROOMS screener emerges as a valuable tool that empowers dental offices to better understand and address oral dysfunction.

BROOMS was developed by two myofunctional therapists, Brittny Sciarra-Murphy and me, who had prior experience screening in our dental operatories. As dental hygienists, we understood the necessity for a screener to fit efficiently into the clinical appointment without adding stress or time. Using our clinical data and experience, they developed the BROOMS screener to serve as a valuable tool that empowers dental offices to better understand and address oral dysfunction and to help dental professionals seamlessly integrate oral dysfunction screening into the routine hygiene appointment.

The screener consists of two columns to check off, making assessment as simple as identifying a yes or no for each section. Two or more marks in the left column, marking affirmative for that section, indicates the need for referral to a myofunctional therapist for further evaluation. Here's a breakdown of BROOMS’ components and how it can revolutionize the way dental professionals assess oral health. (Click to download the BROOMS screener)

Bruxism: The "B"

Bruxism, the grinding or clenching of teeth, has long been a subject of interest in dental research. Findings reveal a direct correlation between bruxism and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Intriguingly, bruxism events tend to occur after apnea episodes and are seldom associated with central sleep apnea.1 This discovery suggests that bruxism may serve as a mechanism to aid in reopening the airway following a collapse, highlighting its significance in understanding OSA.2 Dental professionals can detect signs of bruxism by observing intraoral manifestations, such as occlusal wear. These observations are a crucial component of the BROOMS screener, providing valuable insights into a patient's oral health.

You might also be interested in: The dental hygienist's role in screening for sleep apnea

Respiration: The "R"

The "R" in BROOMS emphasizes the importance of assessing a patient's respiration mode, and it highlights the tremendous benefits of nasal breathing. Nasal breathing is the body's natural and preferred way of taking in oxygen. It serves as a critical function that extends beyond oral health, impacting overall well-being. When patients predominantly breathe through their noses, several advantages come into play.

First and foremost, nasal breathing acts as a natural filter, purifying the air by trapping allergens, dust, and harmful particles before they reach the lungs. This filtration process aids in reducing the risk of respiratory allergies and illnesses. As well, nasal breathing helps humidify and warm the inhaled air, preventing irritation of the respiratory tract and minimizing the likelihood of dry coughs and sore throats.

Nasal breathing also contributes to more efficient oxygen exchange in the lungs. The nasal passages are lined with specialized tissues that produce nitric oxide, a molecule that helps dilate blood vessels and improve oxygen uptake by the body's cells. This results in better oxygenation of tissues, improved energy levels, and enhanced cognitive function.

In the context of oral health, nasal breathing is a key indicator of proper respiration. Patients who habitually breathe through their mouths may experience dry mouth, which can increase the risk of dental decay and gum disease. Additionally, open-mouth breathing can lead to poor tongue posture (see "open mouth resting posture" below), further emphasizing the interconnectedness of the components in the BROOMS screener.3

By recognizing the advantages of nasal breathing and addressing issues related to mouth breathing, dental professionals can contribute not only to their patients' oral health but also to their overall quality of life. The assessment of respiration mode, as part of the BROOMS screener, plays a crucial role in identifying and mitigating potential issues related to oral dysfunction and general well-being.

Oral defensiveness: The first "O"

The first "O" in BROOMS emphasizes the significance of oral defensiveness. Orally defensive patients often exhibit high posterior tongue positioning, leading to an obstruction of the oropharyngeal space. They may also display a hyperactive gag reflex or strong reflexive muscular reactions to intraoral touch, especially around the lips.4 Identifying these signs allows dental professionals to address respiratory dysfunction promptly, preventing further complications.

Open mouth resting posture: The second "O"

The second "O" in BROOMS emphasizes the significance of open mouth resting posture. This seemingly simple observation can provide valuable insights into a patient's oral health. A patient with open mouth resting posture is indicative of mouth breathing and, more important, improper tongue rest posture. Low tongue rest posture is easily observable and informs the clinician that the patient lacks proper oral resting posture. Correcting this posture is vital for overall oral health and function.

Maxillary transverse width: The "M"

The “M” in BROOMS delves into maxillary transverse width, which is a direct result of a patient's history of proper tongue rest posture. A narrow and vaulted palate correlates with a narrow nasal floor, reducing the volume available for nasal breathing. This limitation may impact the patient's ability to breathe physiologically through the nose. Measuring the maxillary arch can be as simple as checking if a cotton roll fits between the two first molars. According to the Bogue Index, the ideal transverse intermolar width is 45 mm by age 18. Assessing maxillary transverse width aids in understanding a patient's oral health history and potential breathing issues.

Strained mentalis: The "S"

The final letter in BROOMS, "S," draws attention to strained mentalis. Every dental hygienist can likely recall a particular patient they have engaged in what I like to call the “mentalis war.” When trying to scale the mandibular anterior teeth, the compression of the mentalis against the fulcrum finger and instrument is strong and frustrating. This along with a bunched appearance, similar to the dimpling of an orange, suggests the presence of strained mentalis muscles, which may be a sign of compensatory facial muscle function.5

The BROOMS screener introduces a comprehensive approach to screening for oral dysfunction, offering dental professionals a powerful tool to enhance patient care. By understanding the significance of bruxism, respiration, oral defensiveness, open mouth resting posture, maxillary transverse width, and strained mentalis, dental offices can take proactive steps to address these issues and promote optimal oral health. Embracing the BROOMS screener not only contributes to improved patient outcomes but also underscores the pivotal role of dentistry in holistic health and well-being.

Author's note: Learn more about airway health, including an upcoming eight-week comprehensive course on myo practice for RDHs, at Airway Health Solutions.

References

1. Alves AC, Alchieri JC, Barbosa GA. Bruxism. Masticatory Implications and Anxiety.” Acta Odontol Latinoam. 2013;26(1):15-22. Accessed September 23, 2023.

2. Saito, Miku, et al. Temporal Association between sleep apnea-hypopnea and sleep bruxism events.” Journal of Sleep Research, 2013;23(2): 196–203. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12099

3. Vargervik K, et al. Morphologic response to changes in neuromuscular patterns experimentally induced by altered modes of respiration.” American Journal of Orthodontics, 1984;85(2): 115–124. doi:10.1016/0002-9416(84)90003-4

4. Lambrechts H, et al. Lip and tongue pressure in orthodontic patients. The European Journal of Orthodontics, vol. 32, no. 4, 2010;32(4): 466–471, doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjp137

5. Shah N. Muscle function evaluation and the emerging field of oro facial myology: connecting dots with the muscles.” June 2015. scientonline.org/open-access/muscle-function-evaluation-and-the-emerging-field-of-oro-facial-myology-connecting-dots-with-the-muscles.pdf

About the Author

Karese Laguerre, CRDH, MAS

Karese is a registered dental hygienist, myofunctional therapist, author, and key opinion leader in sleep and myofunctional therapy. She founded The Myo Spot, a practice aimed at amplifying oral wellness to whole body wellness. Through teletherapy she helps clients of all ages overcome tongue ties, TMJ disorders, sleep apnea, grinding, anxiety, and various breathing and orofacial dysfunction. Passionate about education and self-help, she published Accomplished: How to Sleep Better, Eliminate Burnout and Execute Goals. She also founded the International Association of Airway Hygienists and currently serves as president of the board.