The edentulous shift: Navigating grief, dentures, and oral pathology in geriatric dentistry

What you'll learn in this article

- The emotional and clinical challenges older adults face during the transition to complete edentulism

- Key oral pathologies associated with dentures and how hygienists can identify early signs

- Effective strategies for patient communication that validate emotional experiences and support adaptation

- The essential role of dental hygienists in preventive care, pathology detection, and ongoing patient advocacy for edentulous patients

Life expectancy is steadily increasing, and by 2050, the global population aged 80 and older is expected to triple. In the US, older adults will outnumber children by 2034 and represent nearly 25% of the population by 2060. Encouragingly, more seniors are retaining their natural teeth. Complete tooth loss has dropped from nearly 50% in 1970 to 17% today, with projections below 3% by mid-century.1,2

For many older adults, the transition to complete edentulism (figure 1) is both a clinical and emotional hurdle. It often brings feelings of grief, loss of identity, and a gradual detachment from routine dental care. However, this stage should not signal the end of the dental hygienist’s involvement. On the contrary, it requires heightened attention.

Dental hygienists are essential in supporting patients through this adjustment, providing education on prosthetic maintenance, identifying early signs of oral pathology, and reinforcing the importance of ongoing preventive care. Their role encompasses more than mechanical upkeep; it involves psychological support, patient advocacy, and sustained engagement.

Tooth loss, frequently resulting from chronic infection, not only alters facial esthetics and reduces masticatory function, contributing to malnutrition, but it also increases the risk of systemic complications. Oral infections can spread hematogenously, affecting prosthetic joints or cardiac implants.3 Through consistent oral hygiene, regular monitoring, and responsible antibiotic management, these risks can be mitigated. This article examines how hygienists can meet the challenges of edentulism with clinical precision and empathetic patient-centered care.

The dental hygienist at the crossroads of change

In many practices, it is the hygienist—not the dentist—who builds the most consistent rapport with patients over time. We are the ones who observe changes in soft tissue, occlusion, hygiene habits, and demeanor. We notice when a once-chatty patient grows silent, when their brushing patterns shift, or when their gingival health deteriorates. When older adults begin losing teeth, it is often the hygienist who first hears their concerns.

Whether the patient is moving toward full edentulism due to periodontal disease, caries, or trauma, we can begin the conversation before the final extractions occur. We provide education not just on prosthetics, but on what the transition means functionally and emotionally.4 Our chair becomes a space for preparation, not only for dentures, but for adjustment, grief, and eventual adaptation.

Grief in the operatory: Naming the emotional weight of edentulism

Tooth loss, especially in later life, carries emotional weight. It may be tied to perceived aging, physical decline, or even shame around neglect or inaccessibility to care.5 Many patients mourn their teeth as they would mourn any part of their body. There may be denial, anger, bargaining (“Can’t you just save this one?”), sadness, and finally—hopefully—acceptance.

Recognizing this grief and allowing space for it is part of therapeutic hygiene care. Our words matter. Avoid phrases like “You’ll get used to it” or “Everyone goes through this” and instead validate the patient’s experience: “I know this is a big change. You’re not alone, and we’re here to support you through it.” By acknowledging the emotional burden, we allow patients to feel seen and respected. This builds trust, which is critical when we need to discuss oral lesions, compliance, or prosthetic complications down the road.

Common oral pathologies in edentulous patients with complete dentures

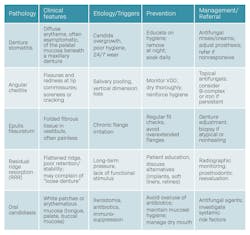

While many dental professionals focus on mechanical aspects of dentures—fit, retention, and occlusion—the hygienist’s role extends to soft tissue assessment and early detection of pathology. Some of the most common conditions seen in edentulous patients include (table 1):

Denture stomatitis: Typically presenting as erythema on the palatal mucosa under a maxillary denture, this condition is commonly associated with Candida albicans overgrowth.6 Contributing factors include continuous wear, poor oral hygiene, xerostomia, and systemic conditions such as diabetes. The hygienist plays a key role in identifying early signs and educating the patient on denture cleaning protocols and nighttime removal.7

Angular cheilitis: Fissuring and redness at the commissures of the lips often point to angular cheilitis. It may result from decreased vertical dimension, candidiasis, or nutritional deficiencies.8,9 A quick extraoral inspection and intraoral correlation can guide appropriate referral or chairside recommendations, such as topical antifungals and denture adjustments.

Epulis fissuratum: Chronic mechanical irritation from an ill-fitting denture flange can result in a reactive fibrous hyperplasia. This lesion typically presents as a folded or lobulated mass in the vestibule,10 often with areas of ulceration at the base. While benign in nature, its clinical appearance may resemble other entities such as irritation fibroma, pyogenic granuloma, or even squamous cell carcinoma, particularly when ulcerated or indurated.11 Early recognition by the dental hygienist is essential, not only to guide timely prosthetic adjustment or replacement, but also to prompt referral for biopsy when the lesion appears atypical or persistent.

Residual ridge resorption (RRR): RRR is a gradual, multifactorial, and ultimately unavoidable process that compromises the bony support for dentures over time. Its progression results from a complex interplay of anatomical structure, masticatory dynamics, systemic bone metabolism, and prosthetic factors. The extent and impact of RRR are influenced by the shape and volume of the residual ridge, the quality and quantity of functional load, and the adaptation and stability of the prosthesis within the oral cavity.12

This continuous resorption directly impairs denture stability and retention, affecting comfort, speech, and mastication. For complete dentures, long-term efficacy is heavily dependent on ridge morphology and how forces are distributed across the supporting tissues. Dental hygienists play a key role in monitoring for signs of RRR, especially when patients report recurrent looseness, sore spots, or require frequent relines. Left unaddressed, RRR can contribute to pressure-related mucosal injury, prosthetic-induced trauma, and even nutritional deficiencies due to compromised oral function.

Oral candidiasis (OC): Beyond denture stomatitis, OC may manifest in several clinical forms, most commonly erythematous or pseudomembranous. The erythematous form presents as diffuse, red, often sore patches typically affecting the palate, tongue, or buccal mucosa, while the pseudomembranous variant appears as white, curdlike plaques that can be wiped away, revealing an erythematous or raw mucosal base beneath. These presentations are not restricted to denture-bearing areas and may extend to the oropharynx, particularly in immunocompromised patients or those with systemic conditions. Xerostomia, immunosuppression, and prolonged use of systemic medications such as corticosteroids, antibiotics, or inhalers significantly increase susceptibility. Ill-fitting or poorly cleaned dentures exacerbate fungal colonization by creating microenvironments of retained moisture and biofilm accumulation. Routine soft tissue evaluations during denture maintenance appointments are critical. They allow the dental hygienist to identify early mucosal changes, differentiate candidal lesions from other inflammatory or potentially dysplastic conditions, and initiate appropriate antifungal protocols or referrals for further evaluation when necessary.13

Patient communication: How and when to talk about dentures

Dental hygienists are often the best-positioned team members to start these conversations early. If tooth loss appears imminent, it’s appropriate to plant the seed by saying things like, “Let’s begin thinking about a long-term plan to keep you smiling and eating comfortably.” If the patient is already edentulous and struggling with adaptation, avoid clinical jargon and lead with empathy: “How are you adjusting to the dentures day to day?” “Have you noticed any soreness, changes in how you eat or speak, or anything that doesn’t feel quite right?”

Use visual aids when explaining anatomy changes (such as bone loss or tissue adaptation), and give patients specific hygiene tasks they can succeed with. This sense of agency helps counteract feelings of helplessness or embarrassment.

Case scenario: Putting it all together

Consider an 84-year-old male patient, edentulous for two years, who presents for his annual recall. He wears his dentures 24/7, reports a burning sensation in the palate, and has begun avoiding salads and hard vegetables. A trained hygienist will note the tissue erythema, educate on the link between overnight wear and stomatitis, and suggest an antifungal protocol in collaboration with the dentist. They will also revisit nutritional counseling and reestablish expectations for nighttime removal, while validating the patient’s struggle adjusting to life without natural teeth. This is a perfect example of prevention, oral pathology in practice, and compassionate care.

Hygiene as a lifeline in geriatric dentistry

Complete edentulism is not the end of oral care; it is the beginning of a new chapter, one in which dental hygienists play an essential role. We educate, we screen, we listen, and we intervene when the silent stories of mucosal disease, discomfort, or despair go unnoticed.

Through empathy, clinical vigilance, and a deep understanding of oral pathology, hygienists can transform this transition from a source of loss to a path of renewed dignity and function.

Editor's note: This article appeared in the November/December 2025 print edition of RDH magazine. Dental hygienists in North America are eligible for a complimentary print subscription. Sign up here.

References

- Weiner S, Flinton R. Geriatric dentistry: a changing paradigm. Quintessence Int. 2014;45(4):279-280. doi:10.3290/j.qi.a31498

- Atanda AJ, Livinski AA, London SD, et al. Tooth retention, health, and quality of life in older adults: a scoping review. BMC Oral Health. 2022;22(1):185. doi:10.1186/s12903-022-02210-5

- Coll PP, Lindsay A, Meng J, et al. The prevention of infections in older adults: oral health. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(2):411-416. doi:10.1111/jgs.16154

- Ástvaldsdóttir Á, Boström AM, Davidson T, et al. Oral health and dental care of older persons–a systematic map of systematic reviews. Gerodontology. 2018;35(4):290-304. doi:10.1111/ger.12368

- Muhammad T, Srivastava S. Tooth loss and associated self-rated health and psychological and subjective wellbeing among community-dwelling older adults: a cross-sectional study in India. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):7. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-12457-2

- McReynolds DE, Moorthy A, Moneley JO, Jabra-Rizk MA, Sultan AS. Denture stomatitis–an interdisciplinary clinical review. J Prosthodont. 2023;32(7):560-570. doi:10.1111/jopr.13687

- Schmutzler A, Rauch A, Nitschke I, Lethaus B, Hahnel S. Cleaning of removable dental prostheses – a systematic review. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2021;21(4):101644. doi:10.1016/j.jebdp.2021.101644

- Martori E, Ayuso-Montero R, Martinez-Gomis J, Viñas M, Peraire M. Risk factors for denture-related oral mucosal lesions in a geriatric population. J Prosthet Dent. 2014;111(4):273-279. doi:10.1016/j.prosdent.2013.07.015

- Freitas JB, Gomez RS, De Abreu MHNG, Ferreira EFE. Relationship between the use of full dentures and mucosal alterations among elderly Brazilians. J Oral Rehabil. 2008;35(5):370-374. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2842.2007.01782.x

- Khalifa C, Bouguezzi A, Sioud S, Hentati H, Selmi J. An innovative technique to treat epulis fissuratum: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2021;9:2050313X211063135. doi:10.1177/2050313X211063135

- Mohan RPS, Verma S, Singh U, Agarwal N. Epulis fissuratum: consequence of ill-fitting prosthesis. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2013200054. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-200054

- Ahmed AR, Bashir A, Waqas M, et al. Assessment of residual ridge resorption in mandible of edentulous patients. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent. 2025;17:277-284. doi:10.2147/CCIDE.S516058

- Patil S, Rao RS, Majumdar B, Anil S. Clinical appearance of oral candida infection and therapeutic strategies. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:1391. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2015.01391

About the Author

Andreina Sucre, MSc, RDH

Andreina Sucre, MSc, RDH, is an international dentist, oral pathology, and oral surgery specialist practicing dental hygiene in Miami, Florida. A passionate advocate for early pathological diagnosis, she empowers colleagues through lectures focused on oral pathologies. Andreina spoke on this topic at the 2024 ADHA Annual Conference, 2023 RDH Under One Roof, and she writes about oral pathology for RDH magazine. Committed to community outreach, she educates non-native English-speaking children on oral health and actively volunteers in dental initiatives.