Improving the quality of chart notes

Dear Dianne,

A terrible thing happened in my office. My boss is being sued by a patient who is unhappy with the dentistry she had done. The patient hired a “bulldog” attorney who has my boss terrified over the lawsuit, plus the attorney has also filed a complaint with our state board of dental examiners. Since this has happened, we feel the need to improve on our chart notes. Apparently, my boss’s chart notes were not as thorough as they should have been, so this has become a wake-up call for us. Would you be so kind as to share the elements of good chart notes and anything else that might help us in case this happens again? I want to do my part to be helpful.

Western RDH

Dear Western,

First, let me say that I’m sorry your boss is having to go through this. Most likely, the doctor has malpractice insurance that will provide legal counsel and assistance. Even so, lawsuits can drag on for years and become a lingering source of stress.

Dental professionals may be asked to defend themselves in a court of law or before a judge in a civil lawsuit. Such violations are called torts. A tort is an injury to a person or his/her property. Without going into too much detail: plaintiffs are compensated through money damages that are awarded when a lawsuit is successful or through a settlement. While we don’t always know the reason for a patient’s malpractice claim, most of the time money is the primary reason. According to CNA, one of the largest malpractice insurance carriers, “The only tangible benefit a patient can gain from a malpractice claim is money. A malpractice claim cannot turn back the clock to prevent the alleged injury from occurring. Nor can it ensure that any corrective treatment for the alleged injury will return the patient to the way he or she used to be.”1

Dental professionals can also find themselves in trouble with their state board of dental examiners. Most state boards have made it relatively easy for patients to file a complaint by clicking the “file a complaint” tab on the dental board website. State boards are mandated to protect the public, so every complaint must be investigated. However, some complaints are not under the purview of the state board, such as fee disputes. State dental boards wield considerable power with a variety of punitive actions, including censure, suspension of license, fines, probation, continuing education mandates, and revocation of license.

As dental professionals, we must always be cognizant that we live in a litigious society. The statistics tell us that every practicing dentist can expect at least one malpractice lawsuit in his or her practice lifetime. The statistics are much higher for dental specialists, with oral surgeons experiencing the most liability risk.

Bearing that in mind, please know that your patient chart notes can be your greatest defense—or worst liability—in the case of a lawsuit. Well-written, thorough chart narratives go a long way in protecting dental professionals, while deficient, poorly written notes can actually be damaging when brought before a state board or a jury. In fact, patient records have been characterized as the only witness with an accurate memory. Too often, the problem of deficient chart notes happens when a dentist or hygienist is running behind schedule and just doesn’t take the time to record thorough details of the visit.

The question is, how much should you write? One test of thoroughness is called the “amnesia” test. Developed by CNA, here is the criteria: “If you were to forget everything you ever knew about each and every one of your patients, but you remembered everything you know about how to practice dentistry/dental hygiene, you would be able to read any one of your patient charts and quickly be able to:

- know what treatment the patient has had and why, and

- perform whatever treatment is next for that individual and know why it is necessary.2

Let’s pretend that something tragic happens to you, and someone else has to step in to take your place and care for your patients. That person should be able to read your chart notes and determine exactly what treatment was performed at each appointment, why that treatment was necessary, and what treatment is next—based solely on your documentation. As well, your documentation should meet all the record-keeping requirements of your state board.

Here are some elements of good documentation:

- Make all entries factual.

- Record the date and time.

- Make sure all handwritten entries are legible.

- Use standardized abbreviations.

- When using electronic records, don’t skimp on chart notes.

- Make all entries thorough and complete.

- Use quotation marks for patient complaints or comments, such as “my gums feel so much better now.”

- Record all narratives before the patient is dismissed from your chair. Don’t wait to do chart notes at day’s end when you’re tired and likely to have difficulty remembering details.

- For computerized charts, require that anyone who makes a chart entry type his or her name or identifying number at the end of the entry.

Currently, many dental practices are still using paper charts. However, dental schools are training their students to use electronic health records (EHR). As baby boomer dentists retire and sell their practices to younger dentists or corporate entities, conversion to EHRs is often the first order of business.

Following are some tips concerning information that should NOT be included in patient narratives, some of which pertains to paper records:

- Do not use correction fluid to correct errors.

- Do not skip lines between entries or write in margins.

- Do not write disparaging or subjective comments or abbreviations about the patient, such as “patient is a jerk,” “patient is nuts,” or “PITA.”

- Do not write disparaging comments about previous providers.

- Do not record the patient’s daily fees in the progress notes. Fee amounts are not considered part of a clinical treatment record.

- Do not use words that are ambiguous or vague. “Periodontal diagnosis: poor” does not adequately describe the clinical findings or the true diagnoses. A better narrative would be “Periodontal diagnosis: generalized chronic periodontitis.”

- Do not record information that requires follow-up action on your part if you’re not going to take that action. For example, writing “Patient to be seen in 3 days for reevaluation” places the onus for evaluating the patient’s subsequent status on the clinician.

- Do not use language that suggests carelessness or negligence. Example: “I hadn’t noticed the ulceration at any of the previous appointments.”

- Do not write inflammatory chart notes disparaging other coworkers. “Former hygienist should have dispensed chlorhexidine” or “Calculus remaining at 19D from previous appointment.”

- Do not erase previously charted restorations to show them completed. This is considered record adulteration.

- Do not record telephone conversations with attorneys, risk managers, claims specialists, or insurance agents.

It is recommended that patient financial information be included in the progress notes only when the financial issue directly relates to the delivery of patient care or a patient’s treatment decision. An example of a recommended financial reference would be when a patient declines your recommended treatment or opts for a less expensive alternative due to financial reasons.

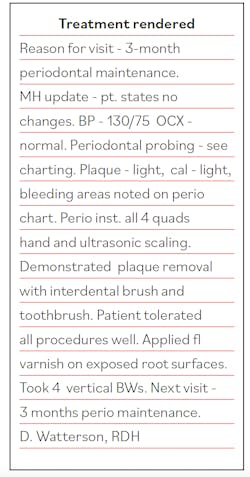

Here is an example of a thorough narrative for a dental hygiene visit:

It is unfortunate that your office is having to endure the stress of a lawsuit. However, this is a great opportunity to improve on chart narratives moving forward. I hope the information I have provided will help in those efforts.

Editor's note: This article appeared in the October 2021 print edition of RDH.

References

1. Dental Professional Liability Risk Management Program. CNA. 2013; 9.

2. Dental Professional Liability Risk Management Program. CNA. 2013;135.

Dianne Glasscoe Watterson, MBA, RDH, is a consultant, speaker, and author. She helps good practices become better through practical analysis and teleconsulting. Visit her website at wattersonspeaks.com. For consulting or speaking inquiries, contact Watterson at [email protected] or call (336) 472-3515.

About the Author

Dianne Glasscoe Watterson, MBA, RDH

DIANNE GLASSCOE WATTERSON, MBA, RDH, is a consultant, speaker, and author. She helps good practices become better through practical analysis and teleconsulting. Visit her website at wattersonspeaks.com. For consulting or speaking inquiries, contact Watterson at [email protected] or call (336) 472-3515.

Updated June 30, 2020