Periodontitis, mental health, and the postpandemic future

The stigma associated with common mental health disorders such as depression and anxiety is declining.1 As a society, we have become more aware of how mental health affects the body, and more willing to discuss psychological suffering with health-care providers.

Even so, many patients may not make the connection between their periodontal and emotional health. Considering this information in your role as a health-care provider promotes patient well-being and elevates the dental hygiene profession.

Feeling the pressure

The significance of the periodontitis-depression relationship has changed in the past two years. The coronavirus pandemic has made conflicting impacts on the dynamics of systemic inflammation and oral and mental health.

Oral health status has been linked to overall COVID-19 severity.2 On one hand, awareness of how COVID-19 has been especially deadly in patients with chronic inflammatory conditions, and how inflammation itself plays a significant role in its clinical progression,3 has changed the way many people think about oral inflammation.

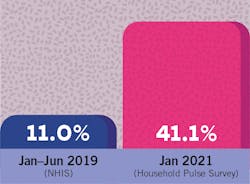

On the other hand, the pandemic’s social and economic effects have increased the incidence of mental health disorders, overall stress, and substance abuse (figure 1). Economic consequences such as job loss have also made both dental and mental health services harder to access.

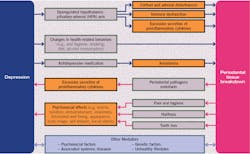

Depression may cause periodontal disease by supporting a chronic dysregulated hypothalamic pituitary-adrenal axis (i.e., the human body’s central stress response system). “Animal studies have demonstrated that various classes of antidepressants can reduce levels of oxidative stress markers, increase several endogenous antioxidants, and also decrease periodontal disease severity… Captivatingly, these biological processes have been revealed to participate in the etiology of depression and periodontal disease comorbidities, as well, and thus may represent a bridge between these pathologies.”8 Medications used to treat depression and common coping behaviors, such as substance abuse, also damage the oral cavity. See figure 2 for a review of reported results related to these mechanisms.

Periodontal disease may cause depression through many pathways. Depression is associated with a “chronic, low-grade inflammatory response,” and people experiencing depression have higher levels of proinflammatory cytokines. “Critically, periodontal disease is also associated with high levels of systemic inflammation… that may potentiate inflammatory and oxidative and nitrosative stress processes that thus may lead to a vulnerability to depression.”8 Because of the shame and embarrassment patients suffering from periodontitis or edentulism experience, social isolation and stress can also increase vulnerability to depression.

Due to all these factors, Dumitrescu argues that “adopting a collaborative approach (e.g., the common risk factor approach) is more rational than one that is disease-specific.”8

Incorporating this information into practice

As I searched for information about this topic, I found plenty of studies reporting on the association between mental health disorders and poor oral health outcomes. There was much less information available about how clinicians should incorporate it into daily practice. One 2015 article published in the Journal of Indian Society of Periodontology recommended Beck’s depression inventory as a part of “a modern periodontal practice that emphasizes individual diagnosis, treatment planning, and maintenance.”10 Beck’s depression inventory has a long, successful history of use as a screening tool, and is inexpensive and simple.

What about dental professionals who are not in specialty practices, or whose employers may be suspicious of discussing a sensitive issue with patients? The profession of dentistry has a lot of progress to make in incorporating the psychological aspects of the oral-systemic link, but many progressive clinicians are already looking in that direction.

In "Caring for dental hygiene patients with depression and anxiety," Samantha T. Verdadero, BSDH, RDH, writes that, “Although dentists and dental hygienists are not the health-care professionals who treat depression, we can lend time and services to our patients at their time of need. Just as dental providers are advocates for the oral-systemic health link, dentists and hygienists also need to take into consideration the link between oral health and mental health.”11 Her suggestions include:

- Look for signs of depression and anxiety in a patient’s medical history (e.g., the presence of certain medications). Staff should “adopt a helpful, unprejudiced attitude” so that patients do not conceal any relevant conditions.11

- Help patients understand the oral side effects of mental health disorders and the medications used to treat them, such as dry mouth and bruxism. Recommend a variety of relevant products to help patients manage any discomfort.

- Consider the way you're communicating with patients—any kind of “lecturing” (about subpar home care, for example) may be especially harmful for patients with depression and anxiety.

Lingering impacts on health-care providers

Even beyond their shared biological factors, periodontal disease and depression have a lot in common. They are both prevalent and destructive diseases. Their causes are complex and only hazily understood. Both benefit from treatments that require a big-picture view of a patient’s life and needs.

The Kaiser Family Foundation report concludes, “History has shown that the mental health impact of disasters outlasts the physical impact, suggesting that today’s elevated mental health needs will continue well beyond the coronavirus outbreak itself. For example, an analysis of the psychological toll on health-care providers during outbreaks found that psychological distress can last up to three years after an outbreak.”4

Long after the bitter arguments over the pandemic fade, dental hygienists will be treating—and healing—people with real physical and emotional suffering caused by the last two years. You may have even seen your own health decline since 2020 as overwhelming stress was placed on your life and your profession. If there is any way the RDH team can better support you, please do not hesitate to reach out to us.

Editor's note: This article appeared in the March 2022 print edition of RDH magazine. Dental hygienists in North America are eligible for a complimentary print subscription. Sign up here.

References

- Venters N. The past, present, and future of innovation in mental health. NHS Digital. December 23, 2021. Accessed February 8, 2022. https://digital.nhs.uk/blog/transformation-blog/2018/the-past-present-and-future-of-innovation-in-mental-health

- Kamel AHM, Basuoni A, Salem ZA, AbuBakr N. The impact of oral health status on COVID-19 severity, recovery period and C-reactive protein values. Br Dent J. 2021;1-7. doi:10.1038/s41415-021-2656-1

- Buicu AL, Cernea S, Benedek I, Buicu CF, Benedek T. Systemic inflammation and COVID-19 mortality in patients with major noncommunicable diseases: chronic coronary syndromes, diabetes and obesity. J Clin Med. 2021;10(8):1545. Published 2021 Apr 7. doi:10.3390/jcm10081545

- Panchal N, Kamal R, Cox C. The implications of COVID-19 for mental health and substance use. Kaiser Family Foundation. February 10, 2021. Accessed February 8, 2022. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/the-implications-of-covid-19-for-mental-health-and-substance-use/

- Dallas ME. Why depression is underreported in men. Everyday Health. August 20, 2015. Accessed February 8, 2022. https://www.everydayhealth.com/news/why-depression-underreported-men/

- Kato S, Ekuni D, Kawakami S, Mude AH, Morita M, Minagi S. Relationship between severity of periodontitis and masseter muscle activity during waking and sleeping hours. Arch Oral Biol. 2018;90:13-18. doi:10.1016/j.archoralbio.2018.02.021

- Baghaie H, Kisely S, Forbes M, Sawyer E, Siskind DJ. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between poor oral health and substance abuse. Addiction. 2017;112(5):765-779. doi:10.1111/add.13754

- Dumitrescu AL. Depression and Inflammatory Periodontal Disease Considerations-An Interdisciplinary Approach. Front Psychol. 2016;7:347. Published 2016 Mar 23. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00347

- Nakayama R, Nishiyama A, Shimada M. Bruxism-related signs and periodontal disease: a preliminary study. Open Dent J. 2018;12:400-405. doi:10.2174/1874210601812010400

- Sundararajan S, Muthukumar S, Rao SR. Relationship between depression and chronic periodontitis. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2015;19(3):294-296. doi:10.4103/0972-124X.153479

- Verdadero ST. Caring for dental hygiene patients with depression and anxiety. RDH magazine. May 1, 2019. Accessed February 8, 2022. https://www.rdhmag.com/career-profession/personal-wellness/article/16408902/caring-for-dental-hygiene-patients-with-depression-and-anxiety

About the Author

Amelia Williamson DeStefano, MA

Amelia Williamson DeStefano, MA, is group editorial director of the Endeavor Business Media Dental Group, where she leads the publication of high-quality content that empowers oral-health professionals to advance patient well-being, succeed in business, and cultivate professional joy and fulfillment. She holds a master's in English Literature from the University of Tulsa and has worked in dental media since 2015.

Updated May 16, 2023