The laggards of dental hygiene

A closer look at the states that remain opposed to expanding dental hygiene services

BY Suzanne Newkirk, RDH, and Lynne H. Slim, RDH, MS

Since the birth of the dental hygiene profession in the early 1900s, each of the 50 states has charted a different course, and the scope of practice laws for dental hygienists vary widely. Typically, states on the West Coast have emerged with more progressive practice acts, while a handful of states in the Deep South have lagged behind.

According to a 2012 Bloomberg Study, four out of the five worst states for dental health are in the Deep South, with the laggard state of Mississippi ranking No. 1. Over 57% of the population in Mississippi (the highest percentage in the nation) lives in a dental health professional shortage area (HPSA), meaning they have no access to dental care. Over 27% of all seniors in Mississippi have no natural teeth, and according to Bloomberg, only 58.1% of the adult population has seen a dentist in the past year. Alabama, another laggard state, ranks fifth in the nation for worst dental health, with one quarter of its senior citizens being edentulous.1

In the last several years, many members/subscribers of professional dental associations, dental publications, and large dental meetings celebrated their 100th anniversary, including the American Dental Hygienists' Association (ADHA). Centennial celebrations signify pride, tradition, and hope for future innovation. Subsequently, we've witnessed significant changes in dentistry and dental hygiene, including the birth of evidence-based practice.

The translation of clinical research to patient care is underway in dentistry and has been propelled forward by the ADA, which dedicated a portion of its website to evidence-based dentistry several years ago. Around the same time, the ADA started training oral health-care professionals to become evidence-based champions, and the weekend training course is still being offered. According to the 2014 article, "Evidence based dental care: Integrating clinical expertise with systematic research," evidence-based health care is now regarded as the gold standard in health-care delivery worldwide. 2

With more than 100 years of research, technology, and education supporting the dental and dental hygiene professions, dental hygiene has evolved far beyond Dr. Fones' wildest imagination. Alfred C. Fones, DDS, was a visionary who pictured dental hygienists working side-by-side with other health-care workers worldwide, helping humanity en masse. Beginning in 1915, dental hygienists licensed in Connecticut (Fones' home state) were permitted to practice in private dental offices, or any public or private institution under the general supervision of a dentist.3 One hundred years later, almost every state in the nation permits general supervision levels for dental hygienists, with most states sanctioning various levels of expanded function practice acts, such as the administration of local anesthesia and nitrous oxide analgesia. Many states also allow dental hygienists to provide restorative functions, such as applying cavity liners and bases, and placing, carving, and finishing amalgam and composite restorations.4

Considering all of the accomplishments and advances made in dentistry during the last century, it's difficult to understand why there are still a handful of states that honor antiquated practice acts. These states are laggards in dental hygiene practice, and according to publications such as the 2000 Surgeon General Satcher's report, "Oral Health in America," their obstructionist policies are harmful to the public's oral health.5

In 2003, Surgeon General Richard H. Carmona released a "National Call to Action to Promote Oral Health," which built upon Satcher's report in 2000 and underscored the many disparities related to oral health. The report charged individuals, whether community leaders, volunteers, health-care professionals, researchers, or policymakers, to collaborate in promoting oral health and reducing disparities.6

A decade later, the 2014 National Governors' Association report suggests that states consider doing more to allow dental hygienists to fulfill dental needs for the underserved by freeing them to practice "to the full extent of their education and training."7

Throughout the nation, policymakers, consumer advocates, and oral health coalitions have started innovative programs to extend the reach of oral health-care delivery to the underserved by altering supervision and/or reimbursement rules for dental hygienists, and exploring new professional certifications for advanced-practice dental hygienists.7

As of June 2014, 37 states have provisions for dental hygienists to: initiate treatment based on a practitioner's assessment of a patient's needs without the specific authorization of a dentist; treat a patient without the presence of a dentist; and maintain a provider-patient relationship. Sixteen of the 37 states permit dental hygienists to receive direct Medicaid reimbursement.4

These innovative programs show an increased use of dental hygienists to promote access to oral health care, thus reducing the incidence of serious tooth decay and other dental disease in vulnerable populations who suffer disproportionally from untreated dental problems. Evidence indicates that these programs are safe and effective.7

Forty-five of the 50 states authorize dental hygienists to work under general supervision, meaning that a dentist has authorized a dental hygienist to perform procedures, but need not be present in the treatment facility during the performance of those procedures. Many of those states permit some form of dental hygiene services in "non-traditional" dental settings, such as clinics, nursing homes, hospitals, and facilities that treat people with developmental disabilities.

Alabama, Mississippi, North Carolina, Hawaii, and Georgia are the only states in the nation where general supervision legislation has not been passed.

The rationale these five states provide for restricting dental hygienists from practicing without the direct supervision of a dentist focuses on concerns about quality and safety, even though no clear evidence exists to support such restrictions. Furthermore, if the basis for restricting scope of practice is a concern about safety and efficacy, these concerns should apply regardless of the income level of the recipient, or the site of care.

For example, even though Georgia is a "direct supervision state" (meaning a dentist must be present in the treatment facility), Georgia dental hygienists working for the Department of Public Health and the Department of Corrections have been allowed to provide preventive dental hygiene services without the presence of a dentist for more than 20 years, with great results.

However, in December 2010, the Georgia Board of Dentistry proposed a rule change that would have limited the ability of dental hygienists to provide basic preventive dental hygiene services in the above approved safety-net settings without a "new requirement" for a prior examination by a dentist. As a result of this egregious action, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) stepped in and urged the Board to reject the proposed amendments because the rule appeared likely to reduce, rather than improve, access to dental care for Georgia's most vulnerable population.7,8

In a letter to Randall Vaughn, division director secretary of State Professional Licensing Boards, the FTC expressed concern about "sound competition policy," and stated that competition should be restricted only when necessary "to protect the public from significant harm," and urged the board to reject the proposed amendments due to "absence of clear evidence that dental hygienists providing services without direct supervision in safety-net settings have harmed or will harm patients."7,8

Yet, the Georgia Board of Dentistry (BOD) still restricts supervision levels for dental hygiene services provided in private practice in order "to protect the safety of the public." This rationale makes one wonder what justification the Georgia BOD could provide to explain why dental hygiene services provided in the above public health settings for impoverished and incarcerated Georgians is considered "safe," but the same dental hygiene services provided without the direct supervision of a dentist in private practice is considered a "public safety" issue, especially considering that 45 of 50 states allow this level of supervision for dental hygienists without safety concerns.

In January 2014, Mississippi Senator(s) Gollott and Dawkins brought forth legislation for general supervision of licensed dental hygienists, but the bill died in committee, despite the fact that Mississippi leads the nation as a health professional shortage area and that expanding access to dental hygienists in public health settings would increase access to care for their citizens.

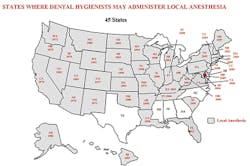

History has shown that dental hygienists are well qualified to provide local anesthesia, thus ensuring patient comfort during nonsurgical therapy of periodontal patients. Alabama, Mississippi, North Carolina, Texas, and Georgia are the only states in the nation where legislation has not been passed to allow dental hygienists to provide local anesthesia for pain management.

Records for safe administration of both infiltration and block anesthesia go back more than 40 years, and teaching the administration of local anesthesia is a required part of dental hygiene curricula for almost all entry-level dental hygiene programs in the U.S. Analysis conducted in 1990 and again in 2005 found no complaints reported to any state boards against dental hygienists for local anesthesia administration.9

Unfortunately, dental hygienists living in the great state of Texas know only too well that not everything there is bigger and better. While Texas has much to boast about, progressive practice acts for dental hygienists is not one of them.

Texas was the last state in the nation to recognize dental hygiene as a profession. In 2005, a Texas Dental Association (TDA) member provided testimony in opposition to a proposal that would permit dental hygienists to provide local anesthesia. The doctor showed a dental needle penetrating into a human skull and stated that it could penetrate into "untoward areas of the brain," thus insinuating that local anesthesia provided by dental hygienists would be a danger to the public.

This misrepresentation of facts makes one wonder where the TDA member received her information or education on local anesthesia, as it has no scientific basis or evidence to support it. There has never been an incident reported in the U.S. of a "needle penetrating the brain of a patient" during the administration of local dental anesthesia provided by either dentists or dental hygienists.

In January 2014, Rick Black, DDS, from El Paso, Texas, stated, "Texas has the 'gold standard' of practice acts in the nation," even though the state lags behind the rest of the country for dental hygiene legislation.

In May 2010, an open forum was held at the office of the Professional Licensing Board in Georgia. It was organized to discuss the implementation of a "pilot program" that would include didactic and clinical training for dental hygienists in a master's program at the Medical College of Georgia (now called Georgia Regents University). It would teach the administration of local anesthesia and nitrous oxide.

Of the 77 people who attended the forum, 66 stated support for the pilot program, while 11 did not. Even though there was overwhelming support from dentists, dental hygienists, and educators, most of the members of Georgia's Board of Dentistry voted in opposition to the program and the program was denied.14

As the above examples from Georgia and Texas indicate, delivery of local anesthesia by dental hygienists may reflect fears of potential injury, even though there is no published evidence in the U.S. of an increased incidence for adverse events, regardless of whether the delivery of the anesthetic was provided via block or infiltration injection.

A recently published argument against dental hygienists performing nerve block anesthesia stated that because intraoral block injections involve injection into main neurovascular bundles, these "blocks" are far more complicated procedures, thus providing a greater potential for causing serious problems.10 However, there are no comparative studies showing that infiltration injections are less likely to cause adverse outcomes than nerve block anesthesia. Reports demonstrate that the adverse occurrences following nerve block anesthesia can also happen during infiltration injections.11-13

In reviewing the publication, "Utilization of local anesthesia by Arkansas dental hygienists, and dentists' delegation/satisfaction relative to this function," Arkansas dental hygienists and dentists viewed this expanded function "as necessary for provision of quality dental hygiene care." The dentist employers reported that local anesthesia provided by dental hygienists "had a positive impact on scheduling, production, patient satisfaction, comfort, and quality of care."15

Perhaps laggard states do not have individuals in authority (such as dental board and dental association members) who are familiar with current literature, such as the Journal of Dental Education's article, "Expanded function allied dental personnel and dental practice productivity and efficiency." This publication clearly demonstrates that practices using expanded function allied dental personnel treated more patients, and had higher gross billings and net incomes than those practices that did not. Thus "the more services delegated, the higher the practice's productivity and efficiency."16

It has been suggested that some laggard states have dental board (and/or state dental association) members that exert pressure on others from making changes in local anesthesia rules and supervision levels for dental hygienists even though the recommended rule changes are scrupulously defensible. Sadly, while the mission of the BOD is to "protect the public," in laggard states they are the ones creating undue harm to the public they have been entrusted to protect by "keeping dental hygienists from practicing to the full extent of their education and training."7

It is important and timely for decision makers in laggard states to develop a new way of thinking (preferably using evidence-based critical thinking skills) and enter a new era in policymaking, one that reflects current standards of care and enhances consumer well-being.

As the nation continues to move forward in its celebration of growth in the delivery of dental hygiene services, those few states holding dear their antiquated practice acts will continue to be the laggards of dental hygiene. RDH

What makes a state slow to change

Donald Berwick, MD, has written about the slow dissemination of innovations in health care, and offers some excellent recommendations for those in leadership positions who wish to accelerate change.17 He advocates the application of available science on the subject, and points out that failure to apply scientific evidence to point-of-care is costly and harmful. The same is true for laggard states who insist on staying the course and resisting change, especially when it affects the delivery of care to underserved population groups.

Social scientists recognize three basic clusters of influence that, in descriptive research, correlate with the rate of spread of a desirable change:

1. Perceptions of a particular innovation

2. Characteristics of the people who adopt the innovation or fail to do so; and

3. Contextual factors such as communication, incentives, leadership, and management.

For example, with local anesthesia as a desired rule change in laggard states, BOD, dental association members, and legislators must perceive benefit of that change. It's a matter of balance between risks/gains and risk aversion in comparing the known status quo with the unknown future if the innovation is adopted.17

If BOD and dental association members in laggard states do not have the values, beliefs, history, and current understanding of needs for local anesthesia administration by hygienists in different practice settings (including scientific guidelines and protocols for nonsurgical periodontal therapy), these needs may not translate to a member's personal belief system. Instead of focusing on efficiency and cost effectiveness, board members and dental association members may feel threatened by hygienists and worry that they are giving up a clinical skill that is uniquely theirs … one that gives them a false sense of superiority and control.

If laggard state board or dental association members feel that an innovation is too complex, it must be simplified. Simplifying change does make a difference and there are countless examples in medicine by social scientists to support this strategy.

Two other perceptions predict the spread of an innovation - trialabilty (Georgia attempted to do this by suggesting a pilot program), and observability (the ease with which potential adopters can watch others try the change first [like trying it out in a school of dentistry first]). When recommended changes have five perceived attributes - benefit, compatibility, simplicity, trialability, observability - they spread faster.17

Individuals who adopt change fall into categories that are often tied to personality traits, according to social science researchers. The majority of potential "adopters" fall into early majority or late majority groups. These groups are not very early to adopt change. Sixteen percent are considered "laggards." They are typically traditionalists, sea anchors, or archivists, and may also be characterized as those who swear by the "tried and true."17

Another cluster of influences on the rate of diffusion of innovations has to do with factors within an organization that encourage (support) or discourage (impede) actual processes of change. For example, persons of influence may discourage change by regarding those who seek to make change as troublemakers.

Suzanne Newkirk, RDH, received her dental hygiene degree from the University of Alaska, Anchorage, in 1981. A recognized key opinion leader in dental endoscopy, Suzanne has published numerous articles on DentistryIQ.com, and has co-authored several dental textbook chapters on minimally invasive nonsurgical periodontal therapy with use of the dental endoscope: "Minimally Invasive Periodontal Therapy: Clinical Techniques and Visualization Technology" by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2014, and "Dental Hygiene: Application to Clinical Practice," publication date 2015. Ms. Newkirk is as a Perioscopy Instructor and professional speaker who has presented all over the nation for doctor and dental hygiene study clubs, as well as many large dental meetings. Suzanne is the owner and moderator of the Perioscopy Users Forum on LinkedIn.

LYNNE SLIM, RDH, BSDH, MSDH, is an award-winning writer who has published extensively in dental/dental hygiene journals. Lynne is the CEO of Perio C Dent, a dental practice management company that specializes in the incorporation of conservative periodontal therapy into the hygiene department of dental practices. Lynne is also the owner and moderator of the periotherapist yahoo group: www.yahoogroups.com/group/periotherapist. Lynne speaks on the topic of conservative periodontal therapy and other dental hygiene-related topics. She can be reached at [email protected] or www.periocdent.com.

References

1. Bloomberg Visual Data: Bloomberg Best (and Worst) Dental Health States. Worst dental health: Mississippi. Over one-quarter of Mississippi seniors have no natural teeth. http://www.bloomberg.com/visual-data/best-and-worst/worst-dental-health-states

2. Kishore M, et al. Evidence based dental care: integrating clinical expertise with systematic research. JCDR. 2014;8(2): 259-262.

3. Fones AC. Mouth hygiene: a textbook for dental hygienists. 2nd ed. Philadelphia and New York: Lea & Febiger; 1921.

4. Practice Act Overview and Direct Access States Map. http://www.adha.org/scope-of-practice, http://www.adha.org/direct-access

5. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health, 2000.

6. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. A National Call to Action to Promote Oral Health. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. NIH Publication No. 03- 5303, May 2003.

7. The Role of Dental Hygienists in Providing Access to Oral Health Care. National Governors Association Paper. 2014. http://www.nga.org/cms/home/nga-center-for-best-practices/center-publications/page-health-publications/col2-content/main-content-list/the-role-of-dental-hygienists-in.html

8. FTC Staff Comment Before the Georgia Board of Dentistry Concerning Proposed Amendments to Board Rule 150.5-0.3 Governing Supervision of Dental Hygienists. http://www.ftc.gov/policy/policy-actions/advocacy-filings/2010/12/ftc-staff-comment-georgia-board-dentistry-concerning

9. Scofield JC, et al. Disciplinary actions associated with the administration of local anesthetics against dentists and dental hygienists. J Dent Hyg Winter 2005;79:8.

10. Michigan House Legislative Analysis Section. Senate Bill 1009: Allow dental hygienists to administer local anesthesia. Available at: www.legislature.mi.gov/documents/2001- 2002/billanalysis/House/htm/2001-HLA-1009-a.htm. Accessed June 28, 2011.

11. Kanaa MD, Whitworth JM, Corbett JP, Meechan JG. Articaine and lidocaine mandibular buccal infiltration anesthesia: prospective randomized double-blind cross-over study. J Endod 2006;32:296-298.

12. Gansto GA, Gaffen AS, Lawrence HP, et al. Occurrence of paresthesia after dental local anesthetic administration in the US. J Am Dent Assoc 2010;141:836-844.

13. Daublander M, Muller R, Lipp MD. The incidence of complications associated with local anesthesia in dentistry. Anesth Prog 1997;44:132-141.

14. Georgia Board of Dentistry Board Meeting. June 18, 2010.

15. Professional Licensing Board 237 Coliseum Drive Macon, GA 31217

Page 3 of 10 Board of Dentistry Minutes, Dental Hygiene Committee - Ms. Pamela Bush, RDH.

16. Beazoglou TJ, et al. Expanded function allied dental personnel and dental practice productivity and efficiency. J Dent Educ 2012 Aug;76(8):1054-60.

17. Berwick DM. Disseminating innovations in healthcare. JAMA 2003;289(15): 1969-1975.