Giant cell lesions

These lesions are often confused with periapical cysts and periapical granulomas

Nancy W. Burkhart,EdD, BSDH, AFAAOM

Several names have existed or have been interchanged with the central giant cell granuloma (CGCG), such as giant cell lesion, giant cell granuloma, and giant cell tumor. As we know, granulomas are thought of as a “reparative process,” but reports indicate that these lesions, regardless of what they may be called, can be aggressive and in some cases very difficult to treat. Their recurrence rates can be very high.

This aggressive tendency appears to be even higher in the cases of young adults and children. Although most of these types of growths tend to be in a nonaggressive form, the younger patient who presents with a more aggressive form may be diagnosed with a larger lesion, more pain, and paresthesia. The parents of the young patient will be very worried about their child, and management for all of those involved becomes very complicated emotionally. The earlier that the CGCG is detected, the sooner treatment can begin, perhaps with less tissue damage. Hopefully, a better outcome may be possible.

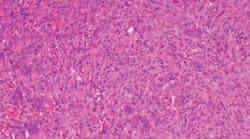

Figure 1: CGCG (Photo courtesy of James J. Sciubba, DMD, PhD)

Many believe that because of its unpredictable and often aggressive nature, CGCG is a true neoplasm; others classify it as non-neoplastic. This topic is controversial and still being debated. It can be said that these lesions are considered to be intraosseous lesions with an unknown etiology.1

The CGCG is considered a hard tissue enlargement, accounting for fewer than 7% of all benign tumors of the jaws. There is a 65% to 75% prevalence for occurrence in the mandible, where the CGCG is most often found anterior to the molar teeth and sometimes in the molar area. The ramus of the mandible is not a common site for development of a CGCG. Although this type of lesion can appear at any age, it favors the under-20 age group. It has also been found in individuals in a wide age range. There is a female predilection of 2:1.

The CGCG lesion is usually discovered on radiographs (figure 1), appearing as a radiolucent lesion with expanding margins. It appears as a multilocular or a unilocular well-defined radiolucent lesion. CGCG lesions may be confused with periapical cysts, periapical granulomas, and larger growths such as the ameloblastoma. The first indication of the CGCG may be mobility or expansion of teeth. Although most CGCG lesions occur in the mandible, when found in the maxilla, they may invade the sinus floor and the sinus passage, leading to facial asymmetry.2

Clinicians should rule out primary and secondary hyperparathyroidism, diabetes, and endocrine disorders. The term “brown tumor” is used in this case. Treatment of the hyperparathyroidism resolves the tumor, so a correct diagnosis is extremely important. Secondary hyperparathyroidism develops in patients with chronic renal disease. Other considerations may be: cherubism, giant cell tumors involving Paget’s disease, aneurysmal bone cysts, ameloblastoma, and odontogenic keratocyst.

The treating clinician would obtain calcium, phosphorus, and alkaline phosphatase levels to rule out any of the conditions mentioned above. Other symptoms of renal disease may be dry mouth, decreased saliva, metallic taste, and others associated with dialysis. As with all tumors and any growth, a complete assessment of the patient is needed for a definitive diagnosis.

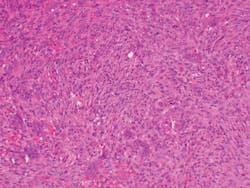

The lesion in Figure 2 shows spindle-shaped mesenchymal cells with focal aggregates of small multinucleated giant cells.

Figure 2: CGCG histology depicting small nucleated giant cells. The stroma is that of fibroblasts and fibrosis. (Photo courtesy of James J. Sciubba, DMD, PhD)

Complete excision by curettage is the recommended treatment. A recurrence rate of 15% to 20% is noted. The more aggressive lesions tend to recur more often, and the lesions found in children are usually the ones with a higher rate of recurrence. The prognosis is good with complete removal.

Recent studies have reported data suggesting that pharmacological agents have a role in the treatment of the CGCG, along with surgical treatment in a long-term retrospective cohort study.3 Some reports of osteonecrosis and growth deficiencies have also been reported with the pharmacological treatments. One study suggested intralesional steroid injections with good results in nonaggressive lesions.4

Hygienists may be the first to detect a radiographic image of these lesions and report their findings to the dentist, oral surgeon, oral pathologist, or oral medicine professional. Some believe that the CGCG should be part of the differential diagnosis when any periapical radiolucency is being considered.2 Patients—or in the case of young children, parents of the patient—may report pain or other symptoms such as tingling/numbness, tooth movement, or diversion in the more aggressive forms. Once a patient is diagnosed with such lesions, the hygienist may also be crucial in any monitoring of the patient during routine visits.

Reviewing medical and dental findings prior to treating a patient is vital to positive outcomes since recurrence rates of CGCG are high. Early treatment for any dental issue results in less surgery, less tissue damage, and less emotional trauma for both the patient and the family. The scope of practice for the RDH has increased in many states within the United States as well as in other countries. This new and increasing standard of care involves not only more responsibility but also greater accountability of the clinician.

As always, continue to ask good questions and listen to your patients!

References

1. Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Chi AC. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016.

2. de Oliveira JP, Olivete F, de Oliveira ND, et al. Combination therapies for the treatment of recurrent central giant cell lesion in the maxilla: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2017;11:74. doi:10.1186/s13256-016-1173-3.

3. Schreuder WH, van den Berg H, Westermann AM, Peacock ZS, de Lange J. Pharmacological and surgical therapy for the central giant cell granuloma: a long-term retrospective cohort study. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2017;45(2):232-243. doi:10.1016/j.jcms.2016.11.011.

4. Dolanmaz D, Esen A, Mihmanlı A, Işık K. Management of central giant cell granuloma of the jaws with intralesional steroid injection and review of the literature. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;20(2):203-209. doi:10.1007/s10006-015-0530-5.

Additional resource

• DeLong L, Burkhart NW. General and Oral Pathology for the Dental Hygienist. 3rd ed. Baltimore, MD: Wolters Kluwer; 2019.

NANCY W. BURKHART, EdD, BSDH,

AFAAOM, is an adjunct associate professor in the Department of Periodontics-Stomatology, College of Dentistry, Texas A&M University, Dallas, Texas. Dr. Burkhart is founder and cohost of the International Oral Lichen Planus Support Group (dentistry.tamhsc.edu/olp/) and coauthor of General and Oral Pathology for the Dental

Hygienist, in its third edition. Nancy was awarded an affiliate fellow status in the American Academy of Oral Medicine in 2016. She was awarded the Dental Professional of the Year in 2017 through the International Pemphigus and Pemphigoid Foundation and is a 2017 Sunstar/RDH Award of Distinction recipient. She can be contacted at [email protected].