Why was it pink? Glass ionomer dental sealants continue to fare well as an option for caries control

By Shirley Gutkowski, RDH, BSDH

The first glass ionomer sealant material came onto the scene in the early 2000s. Immediate confusion and intrigue surfaced in the dental hygiene community. Dental hygienists wanted to know a few things right off the bat. Why was it pink? And, how come it's pink? And, when will the company come out with a sealant that wasn't pink?

The dental community was also a hard sell because glass ionomers used for fillings are pretty soft. If you try to use it to fill a tooth, the material will wear pretty fast. For a Class V location or root surface in a person in a long-term care facility, the material is awesome.

Let's take a minute to reconnect to what a sealant is and what a glass ionomer is. A sealant is a material that fills in the pits and fissures of a posterior tooth, where there is highest chance of decay. The reason for a sealant is to prevent decay.

In the sealant field, a few different materials are in two main categories: resins (plastics) and glass ionomer. A third category is a hybrid of the two. There are subcategories in all three, but we'll just consider the two main categories. The differences between the glass ionomer and resin materials are pretty dramatic. One is notoriously technique sensitive, inert, and acts only as physical barrier in the pits and fissures. The other is dynamic.

Glass ionomers physically block the pits and fissures too, and then release and absorb fluoride. Even more dramatic than that, it fuses to the enamel without the etching step on a moist tooth. Studies evaluating the benefits of glass ionomers show a positive effect the adjacent and the opposing tooth too. This makes it a great product to use as a traditional sealant as well as on the proximal surfaces protecting two teeth with one application to one tooth.

But this is where things get tricky. Readers are probably thinking: Hey, why are resin sealants even still players in the sealant world if glass ionomers release and absorb fluoride from the toothpaste our patients are using? Because they're perceived as soft.

Here's what people are missing. When sealant studies are done there's a really big category called "retention." If you don't prepare the tooth, resin sealants pop off or break apart. If they're not visible, they are not there-not so with glass ionomers. They fuse to the enamel. They may rub off until you can no longer see them, but they're still there.

If the material is no longer visible to the naked eye in most studies, the sealant is counted as failed. Glass ionomer may seem to break apart, but there's still an invisible-to-the-naked-eye coating on the tooth providing a fluoride reservoir. SEM photography shows that the sealant itself can fracture, leaving a thin covering of material fused to the tooth-fused without an acid etch step.

It's no secret that sealant application is very technique sensitive. If it's not done right, it's not done. Keeping the tooth dry, managing the etchant, keeping the tooth dry, managing the patient, keeping the tooth dry, making sure the material is placed in the pit and fissures, not too much, and managing the tongue make for a challenging procedure for a single practitioner. The worst case presentation is a six-year-old with stainless steel crowns on four primary teeth. Urgency ensues, everyone wants to seal that erupting molar as soon as possible.

Many clinicians see a partially erupted tooth in a mouth at high risk for decay and feel compelled to place the sealant right then and there. Can't do it. You'll be dooming the tooth for a sealant bomb. Molars take about 18 months to erupt. Plus, they are hypomineralized for nearly that entire time, making it nearly impossible to etch and retain a resin sealant. Placing a resin sealant on an erupting tooth dooms the tooth by blocking access of the mineralizing saliva. The chemistry of the tooth enamel with the etchant doesn't work, and it's likely the resin sealant will fall off. Operator error in case selection and tooth preparation may be the biggest reason a resin sealant pops off. A glass ionomer sealant can be fearlessly placed on a tooth with an operculum.

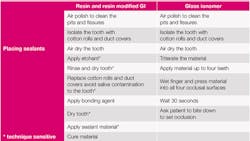

TABLE 1:

TABLE 2:

Regardless of the material used, the tooth must be cleaned correctly before you put anything on there. The best way to do that is to use an air polisher. And the best air polishing powder is one that can remove necrotic enamel and build up damaged enamel, and that is a bioactive glass (Sylc Velopex).

The highest risk population in low income clinics has hygienists under the worst possible conditions placing the most technique sensitive resin sealants without properly preparing the tooth. A prophy brush is not the right tool for this job. Inadequate suction is nearly a given. Then the application of the recommended bonding material and the curing.

The glass ionomer is a little more forgiving in tooth prep. There's no etching step. The tooth should be clean, but etching and bonding isn't necessary. The tooth must be wet. Not swimming in saliva or water, just wet. The material is self-curing, that means no light. Now you're wondering what the drawback is. You'll need to replace the curing light with a triturator. Note to the purchasing department: a triturator is much much less expensive than a curing light.

Lastly, what about that color? One of the very little known components of enamel is strontium, and strontium is what gives the pink glass ionomer sealant its color. "There is a negative correlation between strontium and the occurrence of dental caries" is research paper talk for "teeth with a good concentration of strontium have less decay."

The pink color is also an indicator of its presence. With the naked eye noticing a tooth no longer has a pink fissure, you can rest assured there's still some coverage and you can safely place a new glass ionomer sealant right over the top of the invisible material and it will fuse together again. The strontium in glass ionomer sealants is also what allows the immature enamel to mature under the sealant. Maturation is not possible under a resin sealant.

We used to think that it was OK to seal over incipient decay with a resin sealant. We used to say that the bacteria would die, because there would be no oxygen and no food. Our understanding of a biofilm has changed in the last decade. We often see research papers talking about homogeneous biofilm. In fact, a homogeneous grouping of bacteria, even with a slime layer, is a large colony. It's true you can block off a colony from oxygen and a food supply. The definition of biofilm is heterogeneous combination of bacteria which acts as an organism.

With the way we now understand a biofilm, some bacteria live on another's waste, and the anaerobic bacteria live in different neighborhoods than the aerobic bacteria and that some bacteria make oxygen. So the ecosystem can be habitable by cariogenic bacteria living under the resin dome. So don't do it, unless you're using glass ionomer.

Glass ionomers are so forgiving in poor working conditions that an entire protocol was developed in the 1990s called atraumatic restorative treatment (ART). The glass ionomer is basically mushed into lesions that extend nearly into the pulp chamber. Larger lesions were minimally prepared with hand instruments. The retention of those fillings and sealants has been tracked for six years and the progression of the decay was arrested.

What does a recent meta-analysis show? Let's try to ignore the fact that out of over 2,800 papers about sealants collected since 1973, only 24 were eligible to be part of the analysis. Ten of the studies looked at glass ionomers and in every important measure, glass ionomer sealant material outperformed its resin iteration:

- 29% lower risk of new carious lesions in those who received glass ionomer sealants over resin sealants in the two- to three-year follow-up.

- In the four- to seven-year follow-up, risk for new caries lesions was down 63% compared to the resin sealant participants.

The authors also looked at resin-modified glass ionomers, which have the same inherent problems with placement as traditional resin sealants. There are some products in this category that are self-curing. In the discussion segment of the meta-analysis, the authors state: "When making clinical decisions, we suggest that clinicians take into account the likelihood that their patients will experience a lack of retention inherent to the sealant material as well as their ability to isolate and maintain a dry field during placement."

Glass ionomers are one of the magical products we have in dentistry. It is extremely forgiving and not moisture sensitive. Let's cross our fingers that more studies take a look at glass ionomers. Currently, two companies offer glass ionomer sealants. Riva is offered by SDI. GC America offers Triage.

The pink color is part of the glass ionomer story so the clinician can see that it's there and not mistake it for a prosthetic use of the material to replace lost enamel. If the pink is no longer visible to the naked eye you can apply a second layer over the invisible layer to reduce fears. The goal of sealants is to reduce the chance for decay in the most vulnerable part of the tooth. Anything less than a glass ionomer may put the tooth at risk.

Shirley Gutkowski, RDH, BSDH, is a practicing dental hygienist specializing in orofacial myofunctional therapy. Her practice, Primal Air, LLC, is in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin. Ms. Gutkowski is also the host of Cross Link Radio, a podcast with timely information integrating oral and systemic health.