Tannerella forsythia: The legend of a red-complex queen

Key Highlights

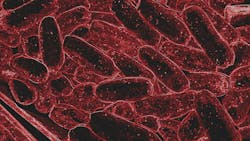

- Tannerella forsythia is a gram-negative bacterium with a fortress-like cell wall that protects it from host defenses and antimicrobial agents.

- It employs the black queen hypothesis by shedding redundant genes, relying on neighboring bacteria for essential nutrients like MurNAc and muropeptides.

- The bacterium uses sialic acid from host glycoconjugates, which aids in immune evasion and supports survival within epithelial cells.

- Tf’s partnership with Fusobacterium nucleatum enhances its ability to acquire nutrients and persist within complex biofilms.

- Understanding Tf’s survival mechanisms offers insights into periodontal disease pathogenesis and potential therapeutic targets.

Part I of 2

There was once an evil red complex queen. Protected behind an impenetrable fortress, she spread disease and captured the white queen of the host. It was foretold there lived a champion, one capable of restoring peace to the microbial realm. Ready to make the first move against her opponent, Alice gathered her muchness and stepped through the looking glass.

Additional reading: LPS: Understanding the powerful immunomodulator in gram-negative bacteria

Identifying pathogens through salivary testing can be one of the greatest moves to checkmate disease. There’s just one Jabberwocky-sized elephant in the room—the periodontally destructive gram-negative Tannerella forsythia (Tf), which keeps crashing the microbial tea party.1 Compared to the infamous and well-studied Porphyromonas gingivalis (Pg), we know very little about Tf. Mysteries surrounding this microbe date back to its discovery.

How the bacteria got its name

Anne Tanner, BDS, PhD, shared with me that while working at Forsyth, her team isolated a dominant species in advanced periodontal lesions. Acting out of the ordinary, this bacteria did not look like any previously described, and it was difficult to grow in a monoculture.2

It did, however, thrive when costreaked with a helper bacterium such as Fusobacterium nucelatum (Fn.)1 Highlighting an unknown growth requirement, the biofilm consortium later proved to be a prerequisite for Tf’s survival.1 For Dr. Tanner’s numerous contributions to the field of microbiology, the anaerobic fusiform (formerly Bacteriodes forsythus) was renamed Tannerella forsythia in her honor.1

As laboratories continue to mine and taxonomically identify the dark matter of the “unculturables,” new periodontal pathogens equally worthy of Socransky’s red-complex status may be discovered. For now, the home of the most virulent belongs to Pg, Treponema denticola (Td), and Tf.3

Survival is typically a bacterium’s number one objective. It’s in the “thriving” department where pathogens really get to flex their genetic achievements. Here I’ll focus on Tf’s mechanisms for survival. Diametrically, Tf’s greatest strengths and weaknesses come from its cell wall.

Tf’s fortress walls

Resembling the stone boundaries of a medieval fortress, cell walls establish a perimeter that safeguards against roaming host armies, antimicrobial therapies, and other bacteria.4 For gram-negative bacteria, the wall consists of a thin exoskeleton, or peptidoglycan (PGN), sandwiched between the inner cytoplasmic and outer membranes.4

Peptide chains link together long strands of amino sugars called N-acetylglucosamine (GLcNAc) and N-acetylmuramic acid (MurNAc), forming the flexible mesh of PGN.4 Within the walls, drawbridge-like gates called transporters are strategically engineered to channel resources into and out of the cell for survival.

Sensing fluctuations in the oral environment and biofilm, bacteria modify and recycle their PGN for growth and viability. Cleaving enzymes begin disassembling the PGN into fragments known as anhydromuropeptides or muropeptides.4 Once released into the environment, the fragments become either messengers in bacterial communication or recovered for later use.3

Useful pieces are gathered, sent through the transporters to the central cytoplasm, and refined into building blocks by specialized genes and enzymes. The enzymes must now work quickly to rebuild the PGN to maintain structural integrity and prevent cellular death.4

The mysterious growth factor revealed

In biology, the red queen hypothesis is used to describe the way bacteria compete through evolution. The black queen hypothesis (BQH), however, describes competitive advantages through the loss of genetic redundancies. In other words, let other bacteria do the heavy lifting.

Following the BQH, Tf shed common genes (murA/MurB and glmS/glmM/glmU) programmed for the enzymatic biosynthesis of MurNAc.1 This clever move likely conserves energy, but without MurNAc, there is no cell wall. Now an obligatory predator, Tf scavenges for nutrients.1 These include MurNAc, muropeptides, and sialic acid.1

Nutrient number one: MurNAc

Finding MurNAc is no problem. As neighboring bacteria recycle their PGNs, “it is conceivable to assume that the polymicrobial flora in the oral cavity” provides plentiful sources of MurNAc and GlcNAc.1 Internalizing and processing the unconventional nutrients is the true challenge.

Thinking again in terms of the cell being fortress-like, carts of MurNAc must bypass the main gate. Instead, it uses an alternate supply entrance called the Tf_MurT transporter. Some of the sorted MurNAc is sent along reconfigured Tf_MurK and Tf_MurQ enzymatic conveyor belts and used for energy.1 Leftovers get processed by the AmgK and MurU enzymes and are selected as building blocks for the PGN rebuild.3

Nutrient number two: Muropeptides

Bacteria select their position within the biofilm based on strict dietary requirements. Tf can grow on MurNAc but has a fondness for muropeptides.1 Anhydromuropeptides and muropeptides (the larger sections of PGN) are significantly more available as cohabiting bacteria perform cell wall recycling.1

Fortunately for Tf, while it employs a Tf_AmpG transporter for this preferred nutrient uptake, nearby neighbors do not.1 T. denticola, Fn, and Pg all lack the specific transporter, leaving a bounty for Tf.1 Moreover, Fn’s ability to generate muropeptides is robust enough to sustain Tf solely.3 Additionally, Tf can use whole sections of PGN from Fn and Pg as a substitute.1

Nutrient number 3: Sialic acid

Biofilm dues are not cheap, and giving back to the community reduces the risk of being booted out by those around you. One currency is sialic acid. Oral epithelial cells are covered in glycoconjugates with terminal sialic acid residues.5 Situated on the outer surface of the biofilm, all three of the late-colonizing red-complex bacteria use enzymes called sialidases to mine sialic acid. These pathogens use this sugar residue as a nutrient or to decorate their cellular surface as camouflage from the host immune response.5

For Tf, this includes the NanH and SiaH sialidases.5 Using the dedicated NanH genes, sialic acid is shuttled into the peptidoglycan synthesis pathway as a substitute for its MurNAc requirements.5 This salvage pathway also facilitates “adhesion to and invasion of epithelial cells.”5 Once Tf is inside epithelial cells, all external sources for MurNAc are cut off, and survival is dependent on sialic acid uptake.5

In what I describe as “biofilm besties,” the partnership between Tf and Fn is synergistically intertwined. Fn has a coat of sialic acid that Tf can use, but Fn is without the sialidase in which to obtain sialic acid for its own. It is in this tight partnership where the two are such strong survivors. Over thousands of years, Tf has learned how to survive and persist in a biofilm.

In part two, I’ll discuss how Tf thrives.

Author’s note: This article is dedicated to Anne Tanner, BDS, PhD, for her contributions in oral microbiology and for inspiring curious hygienists to never stop chasing rabbits.

Editor's note: This article appeared in the January/February 2026 print edition of RDH magazine. Dental hygienists in North America are eligible for a complimentary print subscription. Sign up here.

- Hottmann I, Borisova M, Schäffer C, Mayer C. Peptidoglycan salvage enables the periodontal pathogen Tannerella forsythia to survive within the oral microbial community. Microb Physiol. 2021;31(2):123-134. doi.org/10.1159/000516751

- Emails exchanged with Anne CR Tanner, BDS, PhD

- Ruscitto A, Sharma A. Peptidoglycan synthesis in Tannerella forsythia: scavenging is the modus operandi. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2018;33(2):125-132. doi:10.1111/omi.12210

- Garde S, Chodisetti PK, Reddy M. Peptidoglycan: structure, synthesis, and regulation. EcoSal Plus. 2021;9(2). doi:10.1128/ecosalplus.ESP-0010-2020

- Honma K, Ruscitto A, Frey AM, Stafford GP, Sharma A. Sialic acid transporter NanT participates in Tannerella forsythia biofilm formation and survival on epithelial cells. Microb Pathog. 2016;94:12-20. doi:10.1016/j.micpath.2015.08.012

About the Author

Holly Moons, CRDH

Holly has devoted 25 years to periodontal dental hygiene. She has served in multiple roles on local and state boards, belongs to several study clubs, and continues to publish and speak nationally. Holly advocates for a collaborative dental-medical model focused on reducing chronic diseases. Her passion for microbiology drives her research on polymicrobial synergy, pathogenic virulence factors, and emerging concepts in biofilm expression. Connect with her at [email protected].