Oral manifestations and dental management of bulimic patients: 2 case studies

Key Highlights

- Oral signs of bulimia nervosa include dental erosion, perimolysis, sialadenosis, discolored teeth, Russell’s sign, and soft tissue lesions, which can aid in early diagnosis.

- Case reports highlight the importance of recognizing palatal ulcers and melanotic lesions as potential indicators of bulimia, especially in patients with unexplained dental erosion and soft tissue changes.

- Dental professionals should conduct thorough history-taking and clinical examinations to differentiate bulimia-related lesions from other systemic or local oral conditions.

- Management involves addressing immediate dental concerns, such as restoring damaged teeth and treating soft tissue lesions, followed by referral to mental health specialists for comprehensive care.

- Early detection of periomolysis and other oral signs can prevent further dental destruction and facilitate timely intervention for underlying eating disorders.

Editor's note: This article was coauthored by Deborah Franklin, DDS, MA, D. Le, DDS, Ryan Vahdani, DDS, MHA, MAGD, Christopher Daniel, DDS, MD, MBA, FACS, Gary N. Frey, DDS, Ben F. Warner, DDS, MD, MS, and Cleverick “CD” Johnson, DDS, MS.

All photos are courtesy of and copyrighted by Dr. C.D. Johnson, University of Texas Dental Branch at Houston.

Bulimia nervosa (BN) is one of four eating disorders and described by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) as eating followed by purging. Eating disorders are characterized by severe, persistent disturbance in eating behaviors and are associated with distressing emotions and thoughts.

Oral symptoms of BN include dental erosion, perimolysis, sialodenosis, discolored teeth, parotid gland swelling, Russell’s sign, abrasion, and fractured teeth. Patients often seek consultation with dental providers for dental-related conditions and pain and contributing or accompanying oral problems.

This article presents two case reports on BN. The first presents a 33-year-old female referred from a primary care provider for an ulcerated palatal lesion and multiple melanotic lesions on the tongue and soft palate with comorbid conditions of ADHD, nonspecified hematological problem, and substance abuse. The second case report presents a 35-year-old white female who consulted dental providers due to pain in the third molars with a concomitant erythematous, nonulcerated lesion on the palate

Currently, the DSM-V includes a broad description of behaviors in which individuals consciously refuse to maintain a normal body weight. Specifically, bulimia nervosa includes repeated episodes of binge eating, followed by detrimental behaviors including vomiting, fasting, excessive exercise, and/or excessive use of laxatives and diuretics.

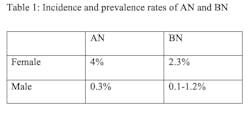

According to the DSM-V, prevalence rates for BN in females is 2.3% and 0.1%-1.2% in males, which shows an increase of BN as compared to the previous DSM-IV criteria (table 1).1 In one study, the prevalence rate decreased, which is thought to possibly have included a lower frequency of binge eating population, once per week that sought care less frequently and were not counted in care-based studies where the severity of purging episodes considers higher frequency (table 2).

Additionally, the overall incidence rate of AN continues to be stable and that of BN is in decline. However, the incidence of AN is increasing in younger people aged less than 15 years. The mortality risk is five times greater for both AN and BN and affects both females and males in western and nonwestern countries.2,3

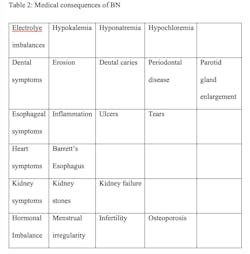

Emotional conditions include low self-esteem, anxiety, depression, and impulsive or self-injurious behaviors. Medical consequences of BN are due to the recurrent nature of the binge-and- purge episodes and upset the electrolyte and chemical balances of the heart and other organ funtions4 (table 2).

The severity of BN is related to the number of purging episodes per week, where mild is rated as one to three times per week. Moderate is assigned if there are four to seven purges per week. Severe is associated at eight to 12 times per week. Lastly, extreme BN is considered 14 or more purges per week.

BN can also be seen clinically in the oral cavity. Persons that suffer from eating disorders share unique patterns of enamel erosion or abrasion. Most eating disorders occur in young white females from highly industrialized countries; however, there is a prevalence of up to 10% in males and the classic dental signs might be less evident in this population. Males tend to use compulsive exercise rather than vomiting to purge to achieve weight loss.

Dentists and dental hygienists are in unique positions to diagnose and identify BN since bulimia behavior is exhibited in the mouth. Symptoms such as dental erosion, perimolysis, sialodenosis, discolored teeth, parotid gland swelling, Russell’s sign, and fractured teeth and abrasion can be recognized during the dental hygiene and dental exams. Patients can then be referred for appropriate medical care. The following describes these oral health conditions.

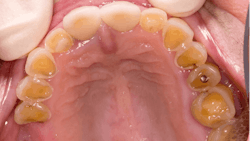

Dental erosion is a chemical process characterized by acid dissolution of dental hard tissue resulting in an irreversible loss of tooth structure. Acid destruction of the dentition occurs with both extrinsic and intrinsic factors. Extrinsic factors are caused by bacteria that produce acidic byproducts in persons that have diets high in sucrose and poor oral hygiene, or diets that are high in acidity. Intrinsic factors such as acid reflux or the purging associated with BN are also causative effects.5 Perimolysis is a specific form of tooth erosion that’s caused from intrinsic factors without bacterial involvement6 (figures 1,2).

Sialdenosis is a non-neoplastic, noninflammatory swelling of the salivary gland in association with acinar hypertrophy and ductal atrophy. Sialdenosis results from systemic metabolic conditions similar to BN. Presentation is of nontender swellings that are often bilateral and symmetric7 (figures 3,4a,4b,5).

Parotid gland swelling occurs in patients suffering from BN. The exact cause of sialdenosis is unclear but the gland receives both sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation with BN and becomes dysregulated, causing hypertrophy. Whatever the cause, with the cessation of bingeing and purging, the parotid glands shrink back to their normal size, indicating a causal relationship.

Discolored teeth are the result of tooth erosion and loss of enamel, which is whiter in color than dentin, which is more yellow. Once the enamel is gone, a darker colored and weakened tooth remains that is subject to fracture and is more susceptible to tooth decay.

Lastly, Russell’s sign is a BN manifestation defined by calluses on the knuckles or back of the hand due to repeated self-induced vomiting and the continued irritation of the affected areas8 (figure 7).

The following two case reports will describe clinical manifestations of BN.

Case study: Clinical case 1

A 33-year-old white female was referred to The UT Health Houston School of Dentistry (UTSD) urgent care clinic from an external dental clinic for evaluation of ulcerated palatal lesions and multiple melanotic lesions on the tongue and soft palate. The patient was an emaciated female who had a labored gait and required assistance to walk. She denied a history of chronic diseases, surgeries, allergies, and tobacco use or substance abuse.

However, her mother provided a sharply contrasting medical history of the patient in a written note. The mother’s information included diagnosis and treatment of ADHD and a recently diagnosed nonspecified hematological problem.

When her mother’s historical accounts were presented to the patient, the patient restated her medical history to include a 10-year affliction with and treatment of BN, which had resulted in a weight loss of approximately 20 pounds in the last five years. The patient stated that she currently purged at least four to six times daily, using her fingers to induce vomiting.

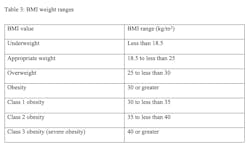

She also used laxatives. The patient further reported a positive history for substance abuse for over 15 years, including cocaine, opioids, and tobacco. She self-reported a height of 5’4” and a body weight of 80 pounds and a BMI of 13.7 (kg/m2). (BMI is an estimate of the fat percentage of a person based on height and weight. Persons with a BMI less than 18.5 are considered underweight according to the CDC). See Table 3.

The patient’s vital signs at her initial appointment were blood pressure 108/75, pulse 76, temperature 98.8 F, and respiration 12 beats per minute. She was alert, aware, and oriented and did not deny her mother’s written note. She had been prescribed the following medications for infection and pain due to dental infections and previous dental extractions by her family physician: Amoxicillin 500mg 1tab QID until gone and Tylenol #3 1tab TID for seven days.

She was also prescribed Seroquel (quetiapine), an atypical antipsychotic, XR 50 mg QD PO divided q12h for mental health care, and Zoloft (sertraline HCL), an antidepressant of the serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), 50 mg PO QD for psychologic depressive disorder. She further stated that she used Milk of Magnesia several times daily as a mouthwash to conceal the smell from vomiting and to lessen the effects of heartburn.

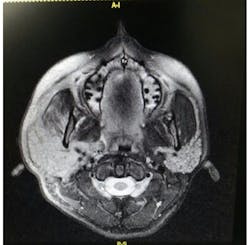

Clinical examination of her oral cavity revealed multiple missing teeth in all four quadrants, and a 3.5 cm erythematic lesion extending from the posterior hard palate to 1 cm onto the soft palate (figures 7,8).

Radiographs indicated that all third molars were missing and the remaining maxillary teeth 3, 5, 13 and mandibular tooth No. 21 were restorable at the time of the examination. The patient was referred to the UTSD Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Department and the Graduate Prosthodontic Department for further treatment. At the two-week evaluation appointment for possible removable appliances, the patient reported an additional weight loss of five pounds and weighed 75 pounds. The patient’s BMI dropped to 12.9. The patient did not return again to the UTSD Urgent Care Clinic and was lost to follow-up.

Case study: Clinical case 2

A 35-year-old white female presented to The UT Health Houston School of Dentistry (UTSD) with a chief complaint of pain in her third molars. The patient stated that she was not taking any medications and had no history of surgeries or allergies. Her vital signs at the initial examination were blood pressure 122/75, pulse 72, respiration 16 breaths per minute, and a slightly elevated temperature of 99.8 F.

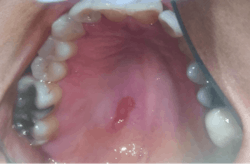

The patient self-reported a height of 5’5” and weight of 125 pounds, BMI 20.8. Oral examination showed a fully dentate individual. Mandibular third molars Nos. 17 and 32 were partially erupted, and both exhibited signs of pericoronitis with negative lymphadenopathy. Her dental history included several amalgam restorations on her posterior teeth. A 4 mm in diameter, erythematous, nonulcerated lesion was noted on the palate (figure 9).

When the patient was questioned about the history of the lesion, she stated that she had just entered a treatment facility for BN. She further stated that she purged three or four times daily and she noticed a slight irritation in the palate but had not noticed the lesion. The patient was referred to the UTSD Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Department for extraction of teeth third molar teeth Nos. 1, 16, 17, and 32. The patient did not appear for her appointment and was lost to recall.

Discussion

Dental professionals are often some of the first health-care professionals to identify patients suffering from BN due to oral symptoms such as abrasion of the soft tissues and enamel erosion that are common in this population.

Several conditions may mimic the enamel erosion found in BN, including tooth erosion due to gastroesophageal reflux disease, methamphetamine use, dental injuries, genetic, mental and emotional illnesses.9,10

Dental management includes addressing any soft tissue lesions and dental erosion with the patient and discussing possible causes for the periomolysis, and a discussion of referral to an eating disorders clinic if needed. As we see in case report 2, the patient’s BMI falls within the normal range. It is, however, the palatal lesion that leads to the discussion of BN, without which might not have happened since the enamel erosion had a mild presentation and was not added to the medical history originally.

Of course, treatment needs for caries, tooth sensitivity, and restoration of severely worn teeth should be presented where restorability allows for direct and or indirect treatment options, as well as preventives such as fluoride. Treatments for eating disorders often include a combination of psychological treatment, medication, and nutritional counseling. Comprehensive treatment may include a multiple interdisciplinary health-care team, especially if the manifestations of the disease are life-threatening. It is essential that the dental professional look beyond the oral injuries and see the entire patient.

Conclusion

Oral lesions in both the hard and soft tissues can mimic conditions associated with eating disorders, as well as those present with substance abuse. Additionally, systemic illness such as oral cancer, viral, bacterial, fungal infection, and other lesions can appear similarly to the traumatized tissues of the oral cavity as that of BN. Careful history taking is important for differential diagnosis.

Dental patients with eating disorders may also present as physically healthy and be considered ASA I patients. Therefore, it is prudent for practicing dental hygienists and dentists to be familiar with the oral manifestations of eating disorders so that they can recognize the oral signs of an eating disorder and refer the patient for proper treatment.2,3,5,8 Particularly, identification of the early signs of periomolysis before more enamel is lost as seen in Figures 1, and 2 is considered optimal.

As shown in the case studies presented, urgent dental needs are prioritized. However, once these needs are met the patient must be referred to a mental health professional and or physician for treatment of the bulimia and the opportunity to prevent further destruction in the oral cavity.

References

1. DSM – IV to DSM – 5. Bulimia nervosa comparison; table 20.

2. van Eeden AE, van Hoeken D, Hoek HW. Incidence, prevalence and mortality of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2021;34(6):515-524. doi:10.1097/YCO.0000000000000739

3. Lavender JM, Brown TA, Murray SB. Men, muscles, and eating disorders: an overview of traditional and muscularity-oriented disordered eating. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19(6):32.

4. Dennis AB, Bulimia nervosa. National Eating Disorders Association.

5. House RC, Grisius R, Bliziotes MM, Licht JH. Perimolysis: Unveiling the surreptitious vomiter. Oral Surg, Oral Med, Oral Path. 1981;51(2):152-155. doi:10.1016/0030-4220(81)90033-5

6. Daniel CP, Ricci HA, Boeck EM, Bevilacqua FM, Cerqueiraleite JBB. Perimolysis: Case report. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1981-8637201500200122397.

7. Adhikari R, Soni A. Submandibular sialadenitis and sialadenosis. StatPearls; August 8, 2022.

8. What is Russell’s Sign? NEDRC Ireland (National Eating Disorder Recovery Center). May 20, 2021.

9. Ogbureke E, Koleini H, Haddad Y, Johnson CD. Typical and atypical tooth erosion in gastro-esophageal reflux: two case reports. J Great Houston Dent Soc. 2015;86(9).

10. Johnson CD, Bouquot JE, Mukherji G. The abused mouth, part II: methamphetamine associated dental injury with a proposed meth mouth. J Great Houston Dent Soc. 2012;84(5).

About the Author

Michele White, DDS

Michele White, DDS, is a general dentist and an assistant professor of restorative dentistry at the UTHealth School of Dentistry where she teaches predoctoral dental students in the preclinic simulation laboratory as well as in the dental clinic. She is the course director for the foundational skills for clinic I and II courses that introduce entry-level dental knowledge and skills to first-year dental students. Dr. White provides dental care to patients in the faculty practice at UT Dentists.