Schedule Control - The Key to Productivity

by Dianne Glasscoe, RDH, BS

Our schedule often determines our stress level. Scheduling for success involves more than just throwing 10 names on a hygiene schedule and getting through the day the best way you can.

Schedules gone awry

Have you looked at your schedule at the beginning of the day and wondered how on earth you were going to survive? Your angst doesn’t come from any particular patient’s name on the schedule (although we all have a few “special” patients who give us a queasy feeling when we see their names on the schedule), but rather the sheer number or arrangement of patients. It’s no secret that when the schedule is too full, we have to cut corners to stay on time. When there are too many intense procedures, such as periodontal scalings in succession, neck and back problems ensue. When too many children are scheduled together, such as several 30-minute appointments in a row, there’s not enough time to do everything, keep the operatory turned over, and stay on time for a solo hygienist. What about the 11 a.m. sealant patient? Will there be anyone to help with patient management in keeping a dry field? What about the periodontal maintenance patient at 12:15 p.m. who smokes and you know will need more than 45 minutes to complete. There goes the lunch hour!

Another schedule wrecker is Mrs. Hotshot who is always and forever late. She seems to delight in throwing the schedule into chaos with her tardiness. And what about poor Mr. Lonely who lost his spouse last year and is starving for attention and conversation? It’s hard to get anything done and stay on schedule because of his desire to talk. It’s also hard not to be rude to people like this.

No doubt about it - our schedules cause lots of stress not only for the clinician but also for the person whose job it is to maintain the schedule. The scheduling coordinator leaves the office on Monday evening with a beautifully engineered schedule for Tuesday, only to find it fall apart when she arrives at work the next morning. Now, she has to scramble to find “warm bodies” to fill the cancellations. Further, the re-engineered schedule might not be as beautiful as the original, but rather a patched-up version with people whose needs might not fit the time actually allotted.

Controlling the schedule

Either the office controls the schedule, or the schedule controls the office. Maintaining control of the schedule means that the scheduling coordinator knows the nuances of how much time clinicians need to do various procedures. Additionally, a good scheduling coordinator knows how to communicate effectively with patients about their appointments.

It is important for clinicians to communicate to scheduling coordinators about the time needed for procedures. Scheduling coordinators cannot read the minds of hygienists and dentists, so there must be a communication tool. Many practice-management software programs allow clinicians to input the time needed for successive visits. Often there is a default time set for various procedures, such as one hour for quadrant scaling, 30 minutes for a child prophylaxis, etc.

When paper charts are used, keep a “Treatment Planning” sheet in the chart printed on heavy stock paper in a different color. This document is the tool the clinician uses to communicate to the front desk about what kind of appointment the patient will need and how many units of time are necessary. Highlight this information in yellow. When the appointment is completed on a later visit, highlight the information in pink, turning the entry orange. This means it has been completed. (See Table 1.)

Additionally, scheduling coordinators must possess excellent communication skills when talking to patients about their appointments. They should never say, “When would you like to come?” This implies the patient can come anytime he or she wants. Try this instead: “The doctor would like to see you as soon as possible for your crown procedure. Fortunately, I have next Tuesday at either 10 a.m. or 2 p.m. Which of those times will work best?” or “Angie would like to see you in three months for your periodontal disease control appointment. Let’s find a good time for you.” It is good to give patients a choice of an afternoon or morning time. If a patient requires a “prime time” appointment, the scheduler should say, “Unfortunately, the first appointment available at that time is six weeks out. But I do have _____.” Encourage the patient to accept an alternate time or date. Some patients will be adamant about coming at a particular time of day, so we accommodate them as best we can.

All staff members, including the doctor, should eliminate the word “cleaning” from their vocabulary. This word trivializes the hygiene appointment. Find a word or phrase that better describes the care, such as preventive care, continuing care, or disease control for periodontal maintenance visits.

Prime time appointments - those first thing in the morning and last thing in the evening - are problematic in some offices. I recommend that these appointments not be scheduled more than eight months out (that’s two months beyond the traditional six months). These appointment slots are often reserved several months past the six-month mark. Schedule control involves setting limits on how far beyond six months the scheduler is allowed to schedule appointments. For example, Mr. Jones requires a 4 p.m. appointment for his preventive care. All of those times are taken up to nine months out (poor schedule control). Say this: “Unfortunately, there aren’t any appointments available at the time you’ve requested. However, I do have _____ or _____” (something close to when he has requested). If he is adamant about a particular time, say: “Since nothing is available, we will have to call you when there is a change in the schedule.” Another technique is to allow a patient a prime time appointment on alternating visits in hygiene. This allows more patients who desire a prime time appointment to get one.

It is more efficient for the hygienist (or the hygiene assistant) to schedule the patient’s next visit before the patient leaves the hygiene operatory if there are computers in the clinical area. The hygienist knows the patient’s needs and how much time will be needed for the next visit. “Mrs. Smith, your next continuing care visit should be in six months. Would Wednesday, June 15, at 10 a.m. or 2 p.m. be better?” If the patient says she would rather not preschedule the appointment, put her name in a pending file. When an appointment is scheduled, give the patient an appointment card with the correct appointment information. Further, the hygienist or assistant should go over the appointment and give the patient a reason for the next visit. “When we see you next time, we will be checking that sensitive tooth (or pocket on No. 30 - something in particular for that patient) plus ...”

Confirmation calls - the bane of scheduling coordinators

Did you know that confirming appointments can actually be counter-productive in some situations? It is true that some patients are annoyed by those calls. In some cases, dependable people do not need to be reminded and can be insulted by the call. Confirmation calls can interrupt something a person was doing or wake a sleeping child. Sometimes patients will use the opportunity to cancel because we made it easy by calling them.

Actually, I do not know of another profession on earth that goes to the lengths we do to ensure people will come to their appointments! Some offices beg and cajole, almost to the point of harassment. The whole idea of confirmation says, We’re not sure you are coming, so that’s why we’re bugging you. I think it is entirely possible that patients live down to our expectations!

As an alternative, I suggest that we start asking patients this question: “Mrs. Johnson, do you require a courtesy confirmation call?” If the patient says no, the scheduling coordinator should say, “Great! I’m going to mark you ‘confirmed’ right now in my schedule. Thank you for being dependable!” If the patient says yes, inform the patient approximately when he or she will be called. (I recommend placing the call two working days before the scheduled visit.) Here’s a good script for a confirmation call:

“Hi Mrs. Jones. This is Mary at Dr. Smith’s office with your courtesy reminder call. Our schedule indicates you have reserved time with our hygienist (or doctor) on Wednesday, May 10, at 9 a.m. We’re looking forward to seeing you then!”

Generally, I do not recommend messages asking patients to “call and let us know you got this message,” except in the case of a chronic offender, because it is punitive to good patients and ties up business assistants with extraneous telephone calls.

When patients schedule their next six-month visit, verify the appointment with the patient. Tell the patient that he or she will receive a reminder card about three to four weeks from the appointment. The person making the appointment should also ask if the patient would like to have a courtesy reminder call a couple of days from the scheduled visit. If the patient says yes, make a note for the scheduling coordinator.

One other noteworthy point is that use of electronic reminders is becoming more and more popular in this day of cell phones and computers. E-mail reminders and text messaging are excellent methods for reminding people of their appointments if they prefer this method. Several services are available, such as Televox® (www.televox.com) and Smile Reminder (www.smilereminder.com).

Scheduling for productivity

The scheduling coordinator has a major responsibility to strike a balance between maintaining productivity and keeping clinicians happy. Also, there are variables in the speed at which hygienists and dentists work.

Many hygienists prefer the one-hour-per-patient regimen, because they feel they have adequate time to deliver high-quality care. In an 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. day, that would mean a maximum of seven patients, assuming everyone comes. However, the problem with this scheduling pattern is that there are so many variables with patients. Some need one hour, some need only 40 or 50 minutes, and some need 30 minutes because they have only a few teeth. Some patients might need more time if periodontal charting and/or radiographs are indicated. Another problem with the one-hour-per-patient regimen is that if somebody disappoints, there is a large block of downtime.

Knowing that the most valuable commodity any clinician has is time, it is important to use that time wisely. Hygienists must be proactive in determining how much time will be needed on succeeding visits. For example, if a patient is healthy periodontally and does not require bitewings or periodontal charting on the next visit, that patient should be given an amount of time commensurate with his or her needs, which would be less than if other services were required. Rather than assigning an arbitrary amount of time for each patient, it is more prudent to schedule time based on each individual’s needs.

A productive schedule is one in which there is little or no downtime and includes a mixture of different procedures such as periodontal scalings or maintenance visits, radiographs, sealants, bleaching trays, prophies, and other adjunctive procedures like fluoride treatments, locally delivered antibiotics or antiseptics, and various products. The industry standard is that one-third of hygiene production should be periodontal in nature. However, that may not be the case in some practices. Practices with a high number of new patients each month typically have more periodontal procedures scheduled. Conversely, those practices with fewer new patients have fewer than average periodontal procedures.

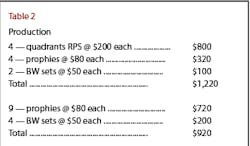

Rational thinking is that the more patients the hygienist treats, the higher the production will be. But most productive procedures, such as periodontal scalings, require longer blocks of time. A hygiene schedule with two (half-mouth) periodontal scalings and four prophy patients will be much more productive than a hygiene schedule with nine prophy patients. (See Table 2.)

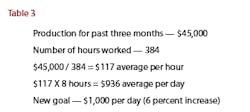

Some offices set a production goal for the hygiene department. Goals are good to give the hygienist a target to work toward; however, they are worthless if attainment or exceeding the goal doesn’t result in a reward of some kind. The best way to set a goal is to divide the total production for the past three months by the number of hours worked. This would be an hourly average that could be multiplied by the number of hours worked in a day. The goal should be set a little higher than the average. (See Table 3.)

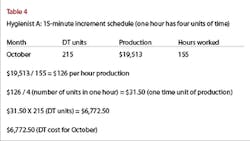

What is the cost of downtime? To put things into perspective let’s consider an example of the high cost of downtime (DT). (See Table 4.)

You can easily see how costly downtime is for a dental practice. If we assumed the amount for October was typical and multiplied the downtime cost in our example - which was for one month only - by 12, the cost for the year would be $81,270!

Additionally, this example does not take into account the hygienist’s wages, which is an expense as well.

Causes for too much downtime can include:

- Weak verbal skills in scheduling/confirmation protocol

- Patients not being held responsible for their appointments

- Not enough patients in the practice or a mass exodus of patients from the practice

- Poorly trained or inefficient business assistants who are not focused on the number one priority of keeping the schedule full

Scheduling tips

I can offer several tips on how to schedule productively. See the box within this article titled “Tips for Productive Scheduling.” With a new outlook on scheduling and an understanding of how it impacts your whole day, you can definitely schedule for success and eliminate the stress!

Tips for Productive Scheduling

- An overbooked schedule will cause the hygienist to cut corners and quality of care in an effort to stay on time, and an underbooked schedule results in low profit margins for the practice. Patient appointment times should reflect the appropriate amount of time needed to deliver high-quality care while being efficient and productive.

- Do not schedule more than two intense procedures back-to-back.

- Do not schedule more than three 30-minute appointments consecutively unless there is a dedicated hygiene assistant.

- Schedule 20 minutes of flex time before lunch and at day’s end.

- Identify chronically late patients by stating their appointment time 15 minutes earlier than the scheduled time.

- Patients who have proven to be unreliable by their history of disappointment should not be allowed to preschedule their six-month appointment. Rather, such patients should receive reminder cards that instruct them to call for an appointment.

- When prescheduling patients six months out, do not completely fill days with appointments. Leave some scattered openings, and block off one day toward the end of the month as a “safety net” day in case patients have to be reappointed due to hygienist absence. If no absence occurs, the day can be appointed with patients who telephone for an appointment.

- Block periodontal scaling time in the schedule to be sure the periodontal patients are seen in a timely manner consistent with treating an infection. To know how much time to block, total the number of periodontal appointments used for the last three months. Divide this number into the total days worked. This will be the average number of periodontal appointments needed on a daily basis.

- When a patient is late, seat that patient and do what you can with the time that is left. Prioritize what is most important and postpone procedures that can be done on a later visit. However, do not feel you have to do everything you had planned to do in only a fraction of the time.

- Communicate with the scheduling coordinator about time needed for individual patients. Understand that scheduling coordinators have a difficult task trying to keep both patients and clinicians satisfied.

- The most productive schedules have a variety of procedures scheduled, including periodontal procedures.

- Confirmation calls should be called “courtesy reminder calls,” and patients should be asked if they require such a call.

- Downtime destroys profitability. Keep downtime to a minimum, and track the unscheduled units of time each month to figure the true downtime cost.

Dianne D. Glasscoe, RDH, BS, is a professional speaker, writer, and consultant to dental practices across the United States. She is CEO of Professional Dental Management, based in Frederick, Md. To contact Glasscoe for speaking or consulting, call (301) 874-5240 or e-mail [email protected]. Visit her Web site at www.professionaldentalmgmt.com.