Light up your career and operatory with lasers—how to jump-start lasers in your practice (Part 2 of 2)

Why diode lasers for the dental hygienist?

While various laser wavelengths and devices are used in periodontics, endodontics, orthodontics, and pediatric, general, and esthetic dentistry, diode lasers are most commonly found in the hands of the dental hygienist.

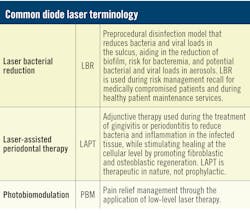

Common laser procedures hygienists perform with lasers include laser bacterial reduction (LBR), laser-assisted periodontal therapy (LAPT), whitening, desensitizing, and the treatment of aphthous ulcers, herpetic lesions, peri-implantitis, and temporomandibular joint dysfunction (TMD) via photobiomodulation.1,2 Diodes have proven to be effective in wound healing and are a significant adjunct during periodontal and implant management therapy appointments for our patients.3 The objective of using lasers in hygiene is to inhibit or eliminate bacterial and viral pathogens and reduce inflammation to promote healing.

“Now more than ever, dental hygienists have the opportunity to inform, educate, and provide treatment for our patients regarding the link with oral care, inflammation, and the impact gingivitis and/or periodontal infection has on the overall systemic health.”—Dangler

Many laser hygienists have already been using LBR as an adjunctive service to reduce the bacterial population prior to scaling in an effort to control potential bacteremia in the bloodstream during the hygiene preventive or therapeutic appointment. With the new importance of aerosol management in our operatories during the COVID-19 pandemic, LBR has become increasingly of interest as a preprocedural modality to minimize sulcular bacteria and viruses. Mounting information supports the cytokine storm and inflammatory effects of COVID-19, which continues to challenge our profession to reevaluate today’s model of care.4-6

“COVID-19, oral-systemic/medical-dental crossover: These circumstances have created a unique opportunity for the dental hygiene profession. There is now the perfect opportunity to increase dental hygienists’ value in the entire health-care profession.”—Press

Why diode lasers for your patients?

One of the many benefits lasers have provided patients is an effective alternative to having surgery or the use of the scalpel. We can reduce patients’ fear and pain by providing them with a conservative, minimally invasive approach, allowing more comfort and an improved experience. The laser’s energy produces a biostimulatory effect that allows the body to repair itself.7

“Diode lasers exemplify how critical technology is to modern dentistry. As clinicians are becoming more knowledgeable about the benefits of laser use in therapy, applying lasers to a wider range of procedures as a standard is dramatically increasing the level of care to the patients.”—Press

This is a real benefit for the patient, as hygienists are not iatrogenically migrating tissue down the roots of the teeth; rather, they are maintaining the natural symmetry of the tissue. Given that the tissue heals itself from the bottom up, the pockets are reduced not through migration or shrinkage but through true healing, more quickly and with less pain.8,9

From pediatric to geriatric patients, lasers have shown to be safe for all age groups. Because there are no known contraindications, they offer an alternative treatment for pregnant or nursing mothers without the risk of post-op medication or analgesics. Pediatric dentists have also embraced laser technology to treat conditions such as tongue-tie. With lasers, the dentist can perform lingual frenectomies more precisely, with minimized bleeding, swelling, and post-op discomfort.

Let’s not forget

Our industry, our patients, and our personal lives have been affected in one way or another by the global COVID-19 crisis. It has required us to take a step back and reevaluate what is important. And while we have been on high alert, let’s not forget how dentistry has been faced with additional global challenges such as the opioid epidemic and antimicrobial resistance.

“We have a professional responsibility to offer our patients alternative treatment that will help reduce or eliminate the need for medication.”—Dangler

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have reported that drug overdose death rates nearly quadrupled in the past two decades,10 while stating that dental professionals have a role and responsibility in effecting change. Additionally, antimicrobial resistance is now noted as one of the top 10 threats to global public health. The International Coalition of Medicines Regulatory Authorities has called on all health-care providers to find alternatives that minimize antibiotic use.11

Laser therapy reduces pain and helps eliminate the need for pain medication.7 We also know that while diode lasers reduce bacteria, they do not cause resistance. With the use of lasers in dentistry, we have and can continue to provide our patients with alternative solutions, and our profession contributes to providing a resolution to another crisis at-large.12

Are you excited to get started using lasers, yet hesitant because you have more questions?

No worries! The following frequently asked questions have been designed to provide clarity for the most common questions asked by other hygienists just like you.

What does bare fiber application mean in LBR?

It is very important that the dental hygienist understand the universal model of treatment associated with the implementation of a laser is “bacterial reduction/disinfection.”8,9 Therefore the standard of care for the integration of a diode laser in dental hygiene is for the purpose of disinfection.13-16

LBR is the treatment standard for laser-assisted hygiene, where emission of standardized low-energy settings and a bare, uninitiated fiber optic is the number one patient treatment model performed by dental hygienists.

Why? Due to the unique principles of laser energy, hygienists are able to perform additional procedures when they use an uninitiated bare fiber tip on warm laser energy settings. This is because no vaporization or ablation of the tissue will occur, thereby allowing hygienists to stay within the duties of their scope of practice.13,14

It is important to note hygienists do not need to initiate the tip or utilize high-power energy settings because they do not cut or surgically remove tissue; rather, they “shine the light” from the laser into the pocket space to create a thermal event that is nonablative and simply decontaminates, ultimately promoting regeneration.

Debris will accrue on the fiber-optic tip. It is important to wipe off any debris with a 2x2 moistened with water during any hygiene-related laser procedure.

Dentists use hot laser surgical energy settings, initiating the fiber by placing the live laser fiber optic against articulating paper, which creates smoke and leaves a carbon residue that darkens the end of the fiber optic. This intentionally focuses the energy toward the target tissue for absorption. This process allows the dentist to use the laser energy more effectively and efficiently for cutting.17,18

“Hygienists are able to successfully use the diode laser with an uninitiated fiber optic to treat their patient’s periodontal infection at every level of diagnosis.”—Press

When is initiation of the laser fiber optic an option?

An initiated fiber optic is applied for intentional curettage of the epithelial lining of the sulcus. Sulcular debridement/curettage is a conscious clinical decision that the patient would benefit from.1,12,14 One such scenario is the intentional removal of necrotic tissue on the surface of the epithelium in a pocket. This is a treatment typically performed for smokers and stage 4 periodontitis, where performing curettage is a diagnostic decision. Another is for the intentional removal and granulation of diseased periodontal tissue.

What happens when you apply laser energy to soft tissues?

Human tissue vaporizes at 100–200°C and smoke (plume) occurs. Dental hygienists stay below this threshold by using the laser between 60° and 100°C, under 1.0 watts continuous wave (CW) of energy.1,7,15

During doctor surgical procedures, a cloud of smoke coming from the vaporizing target tissue creates a plume of smoke as the target tissue is ablated. Plume is the expected byproduct of doctor-performed laser surgical removal of target tissue (e.g., fibroma, frenum release, surgical gingivectomy, etc.).1,17,18

What does it mean if a plume is visible during a hygiene procedure?

It is proper protocol and expected that the hygienist will disengage the foot pedal, stopping the emission of the laser energy before exiting the sulcus, therefore eliminating any concern over a plume occuring.

The potential for laser plume in hygiene procedures can occur anytime an amount of biological debris accumulates on the fiber optic while energy is still emitting from the laser as you clinically exit the sulcus. Plume will only occur if the hygienist exits the sulcus while the foot pedal is still engaged (e.g., while the laser is still emitting energy). The cloud of smoke seen coming off the laser fiber optic tip is accumulated blood, bacteria, and debris during therapy/treatment.

Does fiber-optic selection make a difference in how the laser performs or interacts with the tissue?

Width of the disposable fiber optic: The width of the fiber directly affects the intensity of the applied energy to the target tissue (figure 4). The smaller the fiber-optic width, the more focused/less surface area will be covered by the applied energy. The average fiber optic used by hygienists is 300 or 400 microns wide.12

“Individuals who are confident and prepared to engage in newer technology-based models of patient care will play a huge and important role in helping patients manage their health through the oral-systemic connection and also ensure their dental practice will continue to grow and thrive as we serve the public’s health-care needs!”—Press

What is the difference between continuous wave and pulsed mode selection for energy emission in diode lasers?

Continuous wave: As you depress the foot pedal, the energy is delievered continously to the target. The continuous wave mode is the standard mode used in dental hygiene applications.7,8,18

Gated pulsed mode: Depending on the brand of laser device you are using, the energy is delivered at 20%, 33%, 50%, and 70%. The average diode laser has a 50% pulsed emission mode delivery system. For example, the energy emission interval of on 50% and off 50% occurs 10 times a second. 7,8,18 See Figure 5 for a visual comparison of continuous and pulsed modes.

What is the objective of laser-assisted periodontal therapy?

The objective of LAPT is to leave a clean, coagulated periodontal wound to heal (figure 6).2,3,14 The laser is used as an adjunct during periodontal therapy (SRP) for the therapeutic treatment of gingivitis and stage I, stage II, stage III, or stage IV periodontitis. Prescriptive energy settings to obtain a clinical result have been standardized for therapeutic consistency.

Laser soft-tissue therapy affects a change in the pocket’s bacterial load and leaves a clean, coagulated wound to heal.

LAPT creates new epithelium by increasing fibroblastic and osteoblastic activity, including possible bone density and regeneration of bone in the treated areas.

The therapeutic goal of laser-assisted hygiene is asking the question, “Did the patient heal?” The expectation is that the laser energy assists in eliminating the periodontal infection and supports the physiological regenerative healing process.

During LAPT, the laser is used as an adjunct to scaling and root planing (quadrant therapy) with prescribed energy settings to disinfect (LBR) and support regeneration.14,19

What is the objective of LBR?

Risk management for recare of the medically compromised patient is an additional service offered during periodontal maintenance recall to minimize the risk of new infection.

For healthy recare patients, LBR is an additional service offered during a recall prophylaxis appointment in support of maintaining a healthy patient and minimizing their risk of gingivitis.

Additional laser-assisted procedures

Aphthous ulcer and herpetic lesion treatment is achieved by a process known as biostimulation. There is no direct contact of fiber optic to the lesion or ulcer. The laser fiber is held a couple of millimeters away from the ulcer on the tissue. While in motion, the laser energy is aimed at the lesion, and the patient will feel immediate pain relief as you spiral the released energy toward the lesion. The laser effect reduces discomfort, severity, duration of the outbreak, and has shown to reduce recurrence. Treatment of these ulcers has proven to be a referral opportunity!1,12

Whitening using laser energy creates a photochemical reaction and increases the absorption response to the bleach product applied to the teeth for whitening. Laser energy enhances the effect of tooth bleaching agents for a faster, more effective result.1,12

Tooth desensitization with laser energy creates depolarization of the proprioceptor nerves, therefore lessening the tooth sensitivity and providing immediate pain relief.1,12

What post-op instructions should I communicate to my patients?

For the first 24 hours, stay away from rough and crunchy foods like fried chicken or chips. Avoid vinegar-based foods such as salad dressings and spicy foods such as salsa. These types of foods can irritate the newly treated gingival tissues. Otherwise eat whatever you prefer to maintain your normal healthy diet. Continue to brush daily with your toothbrush using soft strokes. For one week, avoid using your Waterpik below the gumline. For one week, avoid flossing or the use of toothpicks, rubber picks, or microfiber picks below the gumline.

Why are laser safety glasses necessary when using the laser?

Laser energy has a strong affinity to absorption into pigment, so it can cause ocular damage. All dental lasers require eye protection. Laser safety glasses have special lenses that are specifically designed to block the wavelength of light energy coming from the laser device. Every laser comes with three pairs of glasses specific to its wavelength. Each person in the treatment room—whether the doctor, hygienist, assistant, or patient—is required to wear laser safety glasses during procedures.4,14

All additional personnel or patients in the office or outside the treatment room must remain within six feet of the nominal hazard zone. Warning signage and identification of appropriate eyewear should be posted when lasers are in use.7,18

Conclusion

Now more than ever, dental hygienists need to maintain a strong team commitment as a trusted resource, raising our value for the success of the dental practice as a whole. We need to remain efficient, productive, and focused by evaluating patients at the highest level of the medical risk assessment, guiding collaborative treatment decision-making with the doctor, and advising patient treatment acceptance at this most critical time. Understanding advanced technology, accepting the responsibility to gain the skills needed to implement new treatment standards, and embracing necessary professional change will not only secure your future, but ensure the ever-expanding public respect for dentistry as an essential health-care provider.

References

- Coluzzi DH, Convissar RA, eds. Atlas of Laser Applications in Dentistry. Quintessence Publishing; 2007.

- Wolcott RD. Biofilm based wound care. In: Sheffield PJ, Fife CE, eds. Wound Care Practice. 2nd ed. Best Publishing; 2007.

- Ciancio SG, Kazmierczak M, Zambon JJ, Baumgartner S, Bessinger MA, Ho A. Clinical effects of diode laser treatment on wound healing. J Dent Res. (Spec Iss A):2183.

- Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2052-2059. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.6775

- Schett G, Sticherling M, Neurath MF. COVID-19: risk for cytokine targeting in chronic inflammatory diseases? Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20(5):271-272. doi:10.1038/s41577-020-0312-7

- Yumoto H, Nakae H, Fujinaka K, Ebisu S, Matsuo T. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and IL-8 are induced in human oral epithelial cells in response to exposure to periodontopathic Eikenella corrodens. Infect Immun. 1999;67(1):384-394. doi:10.1128/IAI.67.1.384-394.1999

- Coluzzi DJ. Fundamentals of dental lasers: science and instruments. Dent Clin North Am. 2004;48(4):751-v. doi:10.1016/j.cden.2004.05.003

- Moritz A, Schoop U, Goharkhay K, et al. Treatment of periodontal pockets with a diode laser. Lasers Surg Med. 1998;22(5):302-311. doi:10.1002/(sici)1096-9101(1998)22:5<302::aid-lsm7>3.0.co;2-t

- Moritz A, Gutknecht N, Doertbudak O, et al. Bacterial reduction in periodontal pockets through irradiation with a diode laser: a pilot study. J Clin Laser Med Surg. 1997;15(1):33-37. doi:10.1089/clm.1997.15.33

- Hedegaard H, Miniño AM, Warner M. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999-2018. NCHS Data Brief. 2020;(356):1-8.

- Statement from global medicines regulators on combatting antimicrobial resistance. International Coalition of Medicines Regulatory Authorities. https://www.who.int/news-room/events/detail/2019/11/18/default-calendar/world-antibiotic-awareness-week-2019

- Moritz AF, ed. Oral Laser Application. Quintessence Publishing; 2006.

- Aoki A, Sasaki KM, Watanabe H, Ishikawa I. Lasers in nonsurgical periodontal therapy. Periodontol 2000. 2004;36:59-97. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0757.2004.03679.x

- Coluzzi DJ, Convssar RA. Lasers in Clincal Dentistry. Saunders; 2004.

- Bader HI. Use of lasers in periodontics. Dent Clin North Am. 2000;44(4):779-791.

- Rossmann JA, Cobb CM. Lasers in periodontal therapy. Periodontol 2000. 1995;9:150-164. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0757.1995.tb00062.x

- Harrel SK, Molinari J. Aerosols and splatter in dentistry: a brief review of the literature and infection control implications. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135(4):429-437. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2004.0207

- Convissar RA. Principles and Practice of Laser Dentistry. Mosby; 2000.

- Myers TD. Lasers in dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc. 1991;122(1):46‐50. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.1991.0018

Valerie Dangler, BSDH, RDH, is a registered dental hygienist in Arizona, Utah, and Georgia. She received her laser certification at the Las Vegas Institute of Advanced Dental Studies and is board certified to provide dental local anesthesia and nitrous oxide. She serves as a faculty speaker and educator for Align Technology and Biolase, as well as provides training and development for dental team members across the country. She can be reached at [email protected].

Janet Press, RDH, FALD, is a dental hygiene graduate of the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, and has been in general and periodontal specialty practices since 1975. Press holds a fellowship in laser dentistry and received soft-tissue laser certification training in 1995. Internationally recognized in dental hygiene laser education, she has provided laser training in the academic environment as well as the private sector for more than 20 years. Press was named “Distinguished Dental Professional” by Dentsply International and is the owner of 21st Century Dentistry, an approved CE provider for laser certification with training offered throughout the United States. Contact her at janetpress.com.

About the Author

Valerie Dangler, BSDH, RDH

Valerie Dangler, BSDH, RDH, is a registered dental hygienist in Arizona, Utah, and Georgia. She received her laser certification at the Las Vegas Institute of Advanced Dental Studies and is board certified to provide dental local anesthesia and nitrous oxide. She serves as a faculty speaker and educator for Align Technology and Biolase, and provides training and development for dental team members across the country. She can be reached at [email protected].

Janet Press, RDH, FALD

Janet Press, RDH, FALD, is a dental hygiene graduate of the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, and has been in general and periodontal specialty practices since 1975. Press holds a fellowship in laser dentistry and received soft-tissue laser certification training in 1995. Internationally recognized in dental hygiene laser education, she has provided laser training in the academic environment as well as the private sector for more than 20 years. Press was named “Distinguished Dental Professional” by Dentsply International and is the owner of 21st Century Dentistry, an approved CE provider for laser certification offering training throughout the United States. Contact her at janetpress.com.