Case One: “It hurts when I eat”

A healthy, 54-year-old female presented for her routine exam and cleaning. Her chief complaint at the visit was that she had a lump under her tongue on the left side that had been there for approximately two weeks. The patient commented that it hurt when she ate because the food irritated that spot directly. Furthermore, it fluctuated in size to a small degree, but it never really went away.

Figure 1: A view of the patient’s mass

Clinical assessment revealed a tissue-colored raised fluctuant mass on the left side of the lingual frenum, in the area of the submandibular gland duct. There was a slight tenderness to palpation with some firmness to the lesion overall. The mass measured approximately 4 mm by 5 mm in length (figures 1 and 2).

Figure 2: A view of the patient’s mass

Case Two: “My wisdom tooth feels infected”

A healthy 22-year-old female patient presented for a comprehensive examination (figure 3). She had no chief complaints and no caries. The patient was referred to an oral surgeon for removal of wisdom teeth. Following that, all contact was lost.

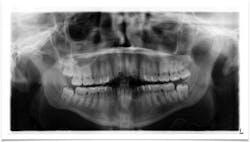

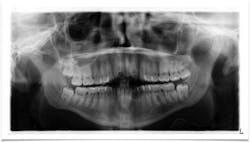

Figure 3: Radiograph from patient’s initial exam

Seven years later, the patient presented with this chief complaint: “Pain in lower right side of jaw that has progressively been getting worse over the course of the last two to three months; it feels like I have an infection in my wisdom tooth.”

A panoramic was taken, and a large radiolucent lesion was noted to extend from the distal of No. 1 to the distal of No. 32. A significant amount of bone destruction in the mandible was observed. Furthermore, a radiolucency was present distal to the crown on No. 17. Clinically, there was inflamed tissue around partially erupted No. 32 that extended up to the distal of No. 2 (figure 4). The area was tender to palpation and unremarkable extraorally.

Figure 4: Radiograph taken at time of complaint

What are your differentials and recommended course of treatment for these patients? Read on!

Case one: Analysis and diagnosis

Differentials

- Mucocele

- Mucus retention cyst

- Sialolith

Discussion

A mucus retention cyst is defined as a “swelling caused by an obstruction of a salivary gland excretory duct resulting in an epithelial-lined cavity containing mucus.”1 The mucus-filled cavity is lined with epithelium2 but rarely involves the major salivary glands.1 Mucus retention cysts can be identified by the following characteristics:

They can occur at any age, but primarily occur in adults who are in their third to eighth decades of life.1

If found in the major salivary glands, 90% are usually in the parotid gland and 10% are in the submandibular and sublingual glands.1 The cysts can resemble mucoceles and low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinomas. The most common sites of occurrence are the floor of the oral cavity, followed by the buccal mucosa and the lower lip.1 Presentation is as a fluctuant, painless, self-contained superficial mass. Treatment is by simple excision, and sometimes the lesions are self-limiting.

Definitive diagnosis: Mucus retention cyst

Figure 5: Radiograph taken immediately after surgery

Treatment and ongoing assessment

In this particular case, the patient was instructed to leave the lesion alone to see how it would manifest over the course of the next two weeks. A follow-up call revealed that the lesion had indeed receded and was, for the most part, gone. Assessment for any changes or questionable pathology in this area will be noted at future recare exams.

Case two: Analysis and diagnosis differentials

Unicystic ameloblastoma

- Benign neoplasm from residual epithelial components of tooth development

- Slow growing, locally aggressive, and can cause large facial deformities; oftentimes will occur in a dentigerous cyst relationship

- Radiographically, lesions appear unilocular, well demarcated with a tooth present within and around the radiolucency

- Removal via enucleation or marginal (block) resection

Odontogenic myxoma

- Aggressive intraosseous lesion derived from embryonic connective tissue

- Primarily found in the premolar/molar area of the mandible and distributed equally in the maxilla

- The slow, often painless growth frequently consists of a “soap bubble” or “honeycomb” pattern

- Oftentimes will resemble an ameloblastoma

- Removal via local curettage or block resection

Dentigerous cyst

- Odontogenic cyst

- Surrounds the crown of an impacted tooth

- Oftentimes asymptomatic, but can produce swelling and pain if large or inflamed

- Radiographically appears as a well-circumscribed radiolucency surrounding the crown of the tooth, oftentimes displacing it and the adjacent teeth

- Removal via surgical enucleation; has a lower recurrence rate

- Ameloblastoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma are different epithelial neoplasms that can arise in dentigerous cysts

Concerns for treatment

The full potential for these lesions must be understood. They can be destructive and life-threatening, especially if malignancy has occurred. A definitive diagnosis must be obtained and rendered as soon as possible. These are the three main concerns: extent of destruction, fracture potential, and permanent paresthesia.

Figure 6: Patient’s three-month radiograph

Treatment

The patient was referred to the oral surgeon for immediate surgery with enucleation (figure 5). A specimen was sent to the lab for pathology, and a liquid diet was recommended for six to eight weeks.

Definitive diagnosis:

Dentigerous cyst

Follow-up

Bone has filled in, no paresthesia is present, and there are no recurrent lesions or abnormal cell formation. No. 17 will be monitored closely with plans for removal when the bone on the right side has healed sufficiently. Figures 6 and 7 are three-month and six-month radiographs, respectively.

Figure 7: Patient’s six-month radiograph

Editor's note: This content was originally published in 2018 and has been updated as of May 2025.

References

1. Sapp JP, Eversole LR, Wysocki GP. Contemporary Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1997.

2. Wood NK, Goaz PW. Differential Diagnosis of Oral and Maxillofacial Lesions. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1997.

Stacey L. Simmons, DDS, is in private practice in Hamilton, Montana. She is a graduate of Marquette University School of Dentistry. Dr. Simmons is a guest lecturer at the University of Montana in the Anatomy and Physiology department. She is the editorial director of PennWell’s clinical dental specialties newsletter, Breakthrough Clinical, and a contributing author for DentistryIQ, Perio-Implant Advisory, and Dental Economics. Dr. Simmons can be reached at [email protected].