Fones and Nightingale: Understanding the evolution of education in nursing and dental hygiene

By Christine Nathe, RDH, MS

Professionally speaking, nursing has been practiced for much longer than dental hygiene. Nursing and dental hygiene actually enjoy professional similarities such as historically beginning with a female-dominated workforce, which continues today. Interestingly, nursing and dental hygiene have followed very different steps when it comes to the evolution of their respective curricula. Understanding the historical evolution of each profession’s education can be helpful when developing solutions to advance future education and improve patient care.

Nursing has documented roots during the height of the Roman Empire in 300 AD but realistically has been around since the beginning of time. The Roman Catholic church was an early advocate in the utilization of nurses to care for others, but there were a variety of advocates throughout the ages. Florence Nightingale opened the first documented nursing school in London in 1860. Nursing education later moved to the U.S. in the late 1800s.1

Initially, nurses were educated in nursing schools, so that students could focus on learning theory as opposed to providing care with little emphasis on the scientific knowledge of health care. This began with Nightingale’s influence, since she knew how difficult it was to train providers who lacked scientific knowledge to care for patients. In fact, many of the early writings suggest that nursing students learning in hospitals were many times used as free labor with little emphasis placed on actually learning standards of care. Nightingale realized the importance of an educated health provider and presented a paper in 1893 that argued for an educated workforce with standards of practice as opposed to one in which nurses served as apprentices (preceptorship) in hospitals.2

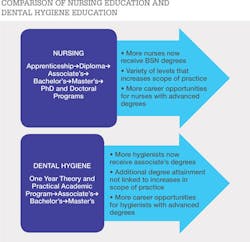

In the 1900s, nursing education was again introduced into the hospitals, which provided hands-on training in emerging technologies, but with theory still being taught.1 These programs typically awarded a nursing diploma. A new, two-year program educating nurses began just after World War II, with the proliferation of community college institutions, which offered an associate’s degree in nursing.3 Bachelor’s degree training began in the 1930s and continues today. As evidence mounts revealing the relationship between higher education for nurses and improved patient outcomes, the movement is progressing.4 There are now a variety of Master’s programs and doctoral programs of nursing throughout the country and these programs lead to an increased scope of practice.

Predating accreditation, the first standard of curriculum for nurses in the U.S. was in 1917, with different accrediting agencies active by the 1920s.5 The National Council of State Boards of Nursing was created to protect the public and strengthen the role of boards of nursing in nursing regulation. This group then developed the first national nursing board exam in 1994, which happened to be the first computerized testing at the time.6

Dental Hygiene Education

Dr. Alfred Fones educated the first dental hygienist, Irene Newman, for one year before he permitted her to treat patients in his practice. In 1913, he started the Fones School of Dental Hygiene, which continues to educate dental hygienists today. Fones recruited instructors and authored the first dental hygiene college textbook before beginning the first program.7 He actually secured experienced professors and experts of medicine, basic sciences, public health, and dentistry from Yale, Harvard, Columbia, and the University of Pennsylvania.8

By 1952, the American Dental Association, Council on Dental Education and Licensure began the accreditation of dental hygiene programs. In 1962, the National Board Dental Hygiene Examination was introduced.9 All states require accreditation by the Commission on Dental Accreditation (CODA) and successful completion of the National Boards (with the exception of Alabama).10

The first bachelor’s degree program in dental hygiene was initiated in 1939 at the University of Michigan.9 The advent of community college dental hygiene programs increased dramatically following World War II and the first master’s degree in dental hygiene programs began in the 1960s, but a significant growth in graduate education did not occur until the 2000s. Although the ADHA adopted a policy supporting the baccalaureate degree as the minimum requirement for practice in 1986, this effort has not yet been successful. Because of the proliferation of entry-level programs, the ADHA advocated for the conduction of a thorough needs assessment before the opening of new dental hygiene program and CODA approved this requirement.11

Levels of Practice

Nursing has had inherent levels. Practical nurses worked under the supervision of registered nurses early on in the U.S. health care system and then took on the subsequent role of the nurse practitioner. Dental hygiene has not had any levels of dental hygienists since its creation. In fact, the scope of practice does not increase based upon degree attainment. Minimally trained dental hygienists can function the same as graduate-level dental hygienists in private dental offices. This is not true when practicing in settings other than private offices, and the increased degree attainment results in diverse career opportunities and increased salaries.12 Dental hygiene has recently proposed levels of practice and Minnesota has an advanced dental therapist model that includes dental hygienists with a master’s degree and an increased scope of practice.13,14

As discussed, historically there were not levels of dental hygienists, but Dr. Fones actually recommended the use of dental hygienists with dental assistant support early on, when talking to the dental boards and associations across the country, which may be closely representative of the relationship between licensed practical or vocational nurses and registered nurses.15 Interestingly, dental hygiene assistants are just now increasing in nature. This may be a side effect of the stagnant use of dental services, hence the need for an increased emphasis on cost-effectiveness within dental practices.

Nursing and Dental Hygiene Comparison

Nursing education seemed to begin in a training mode, with little emphasis on science and theory. That is quite a contrast to dental hygiene, which began with formal training from established professors of science and health care from prestigious institutions. Interestingly, they both ended up with “two-year” colleges during the growth of such institutions after World War II. However, nursing has advanced with multiple types of graduate educational programs, with sound science and practice opportunities for registered nurses. Nurses are more likely now to attain at least a bachelor’s degree16 and many more graduate degrees that result in increased scope of practice and career opportunities in a multitude of venues. This suggests that nursing has kept pace, educationally, with advances in the nursing knowledge base.

Dental hygiene education, although initially focused on theory and practice, seemed to focus on the fast preparation of dental hygienists, with little emphasis on advancement in alignment with the increased knowledge base of dental hygiene. Once community college programs began, this emphasis was again focused on a short span of time learning, with a workforce-readiness focus. Although there are now entry-level bachelor’s degree programs, the community college associate’s degree programs are still in the vast majority.

However, online learning has also increased opportunities for dental hygienists educated at the associate’s degree level to advance to bachelor’s and master’s degree programs. With the increased availability of online education and the increase in the number of master’s programs, trends in education may be changing, since graduate education leads to an increase in research, which leads to an increased knowledge base.

Dental hygiene and nursing have had quite different evolutionary paths of training, although many world influences contributed to changes in training. Both professions have advanced educationally and dental hygiene should model the paths that nursing has taken to advance education, which include linking the increased scope of practice to educational degree attainment. Additionally, the more graduate-educated dental hygienists produced, the more likely dental hygiene will advance in both science and practice, which should ultimately lead to better patient outcomes. RDH

CHRISTINE NATHE, RDH, MS, is director at the University of New Mexico, Division of Dental Hygiene, in Albuquerque, N.M. She is also the author of “Dental Public Health Research” (www.pearsonhighered.com/educator), which is in its third edition with Pearson. She can be reached at [email protected] or (505) 272-8147.

References

1. The history of nursing. Nursing School Hub website. http://www.nursingschoolhub.com/history-nursing/. Accessed February 7, 2017.

2. History lesson: nursing education has evolved over the decades. Nurse.com website. www.nurse.com/blog/2012/11/12/history-lesson-nursing-education-has-evolved-over-the-decades-2/. Published November 12, 2012. Retrieved February 7, 2017.

3. Scheckel M. Nursing education: past, present and future. In: Roux G and Halstead JA. Issues and Trends in Nursing: Essential Knowledge for Today and Tomorrow. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett; 2009:27-61.

4. Blegen MA, Goode CJ, Park SH, Vaughn T, Spetz J. Baccalaureate education in nursing and patient outcomes. J Nurs Adm. 2013;43(2):89-94.

5. History of nursing education. Accreditation Commission for Education in Nursing website. http://www.acenursing.org/acen-history-of-accreditation. Accessed February 13, 2017.

6. NCSBN historical timeline. National Council of the State Boards of Nursing website. https://www.ncsbn.org/history.htm. Accessed February 13, 2017.

7. Ottolengui R. The inauguration of a serious effort to establish a system of education for the dental hygienist. Dent Items of Int. 1914;36(1):6.

8. Motley WE. History of the American Dental Hygienists’ Association 1923-1982. Chicago, IL: American Dental Hygienists’ Association; 1983.

9. Amyot CC. The evolution of dental hygiene education. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene: A Centennial Celebration of Dental Hygiene 1913-2013. 46-48, 50, 52,54-55. http://www.dimensionsofdentalhygiene.com/print.aspx?id=16369.

10. Alabama dental hygiene program: 2017-2018. Board of Dental Examiners of Alabama website. http://www.dentalboard.org/adhp/. Accessed February 8, 2017.

11. FAQs about dental hygiene education programs and accreditation. American Dental Hygienists’ Association website. http://www.adha.org/resources-docs/72617_FAQs_About_Dental_Hygiene_Education_Programs_and_Accreditation.pdf. Accessed February 14, 2017.

12. ADHA Survey of Dental Hygienists in the United States. ADHA: Chicago, 2007.

13. ADHA Focusing on Advancing the Profession. ADHA: Chicago, 2005.

14. Transforming Dental Hygiene Education and the Profession for the 21st Century. ADHA: Chicago, 2015.

15. Alfred C. Fones personal notes. Bridgeport, CT, circa 1902.

16. In Historic Shift, More Nurses Graduate with Bachelor’s Degrees. Robert Wood Foundation website. http://www.rwjf.org/en/library/articles-and-news/2015/09/more-nurses-with-bachelors-degrees.htm. Published September 9, 2015. Accessed February 9, 2017.