Sleep Breathing Disorders

Hygienists on the Front Line

The impact of sleep deprivation affects nearly all the body's systems affected by inflammation. A recent study by the American Academy of Periodontolgy showed that lack of sleep ranked just under smoking as the No. 2 lifestyle factor negatively impacting oral health.

by Kent Smith, DDS, and Shirley Gutkowski, RDH, BSDH

The clock reads 1:00 as you walk into the reception area to claim your first patient after lunch. Mr. Pickwick, however, seems to be disinterested. Who would go to sleep when he is about to be retrieved by his favorite hygienist? If Joe is in REM sleep, he is already inappropriately dreaming about the voluptuous hygienist who cares. He has most likely drifted into Stage 1 sleep and can be easily awakened for his appointment. Maybe he stayed up late to finish a report. Maybe he was kept awake by a newborn. Or, maybe he has a sleep disorder that has yet to be identified by a physician.

Sleep disorders remain unidentified and undiagnosed 90 to 95 percent of the time. In fact, 40 million Americans suffer from a chronic, long-term sleep disorder.1 Starbucks sells 256,000 gallons of coffee every day, and many such drinks are in the hands of those people when they walk into the dental office. If they didn’t show, maybe they overslept — or were arguing with their spouse over the snoring that created interrupted sleep. Nearly 25 percent of sleep partners sleep in separate rooms, and The New York Times reported recently that 60 percent of custom houses would have dual master bedrooms by 2015. So what, right?

Regrettably, a recent survey reported that 76 percent of physicians who are not sleep specialists do not screen their patients for sleep breathing disorders (SBD), and therefore do not refer their patients for testing and treatment. It’s time for dentistry to step up to the plate.

The impact of sleep deprivation affects nearly all the body’s systems affected by inflammation. A recent study by the American Academy of Periodontology showed that lack of sleep ranked just under smoking as the No. 2 lifestyle factor negatively impacting oral health.2 Research is ongoing, but has so far shown that SBDs are implicated in the creation or exacerbation of cardiovascular3 and cerebrovascular4 disorders and diabetes.5 Impotence,6 menstrual irregularities,7 depression,8 and weight gain9 are also implicated in SBD. Add bruxing10 as an additional sequela, and there’s another dental reason to pay attention.

So why should hygienists get involved? Because they are on the front line. Hygienists develop or build a level of trust with patients through a regular interval of health-care treatments unparalleled in medicine. Many dentists believe patients trust hygienists more than they trust dentists.

To include an SBD screening is not as time-consuming as one may think. It’s not just one more thing — it’s done concurrently with other observations. More importantly, it’s potentially lifesaving. Start with the health history. Most hygienists already make a mental note about tobacco use or alcohol. Notice, too, the use of medications that cause a sedative effect. High blood pressure, even controlled blood pressure, is also a red flag.

Next is the overall appearance of the patient. Is he or she noticeably overweight? Obesity is easily the defining catalyst and prognosticator for a compromised airway. It’s also very difficult to lose weight with obstructive sleep apnea11 (OSA), so when the time comes to address the breathing disorder, play that trump card. Related to weight is the circumference of the neck. Most women will not know their neck size. Most men will also not know their neck size, but will think they know. A tape measure in a handy location in the treatment room or pocket, when used often, can quickly develop in the clinician an educated eye for guessing neck sizes. The literature supports a neck size of 17 inches on a man12 and 15 to 16 inches on a woman as being a risk factor for OSA.13 So practice on a few peers, friends, and family members, and impress your patients with a new skill.

So far, observation of the patient on the way to the operatory was a beginning step — no time added. At some point soon, you will be looking in the patient’s mouth. Notice the lateral borders of the tongue. If they are heavily scalloped as in Figure 1, they are more than likely representing the lingual surfaces of the teeth. Why would some tongues have this appearance when others do not? Sometimes it seems like trying to fit three cars into a two-car garage. What is creating this condition? There are several potential reasons:

- It could be that the garage is just too small, and the small arches need orthodontic and myofunctional expansion.

- Perhaps the tongue is posturing forward to alleviate a temporomandibular disturbance.

- Maybe the posterior aspect of the tongue is impinging on the airway, and during sleep, the patient’s tongue is trying its best to push forward and open the airway so the patient can breathe.

- Finally, the patient could be a mouth breather due to allergies or a congested nose and nasopharynx. In the inhalation process, the patient may need to keep the tongue in the floor of the mouth so air can be drawn in.

Regardless, there is a space issue, and one source says that 70 percent of patients with scalloped tongues have sleep disordered breathing. This might be a good time to ask how long he or she has been snoring. The question usually brings a surprised admission and lets the patient know he or she is in the hands of a smarter-than-average hygienist.

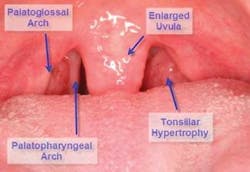

Now look a little more posterior and notice all that tissue back there. A short primer of the anatomy: Palatoglossal and palatopharyngeal arches (collectively known as the tonsillar pillars) house the palatine tonsils. Ideally, the tonsils should be absent or hidden within these walls of tissue. If they extend much past their home, they can contribute to a narrowed airway. The arches should also be pulled back considerably toward the edges of the tongue, unlike Figure 2 where the curtain is half drawn. Additionally, the uvula can become enlarged. All of this excess or redundant tissue interferes with air flow, leading to snoring and obstructive sleep apnea.

Tonsillar tissue can become hypertrophic, particularly in mouth breathers who are unable to use the efficient filters located in the nose and nasopharynx. Because the tonsils are near the entry gate for airborne and alimentary antigens, they become the bodyguards of the airway, becoming infected and swollen themselves to prevent respiratory infections. Additionally, the uvula and other pharyngeal tissues can become swollen from the vibrations occurring during a snorefest, exacerbating the problem.

Now it’s time to observe the occlusal surfaces of the teeth. Look for the acidic effects of GERD. Rather than opening up the contentious GERD vs. occlusion debate, suffice it to say that the effects of stomach acid pouring onto the tooth surface throughout the night are not beneficial. Enamel craters and dentinal pooling that do not correspond to the opposing tooth cusps can come from acid reflux. The surprise is that obstructive sleep apnea has been shown to have a strong association with GERD.

During the apneic event, oxygen levels decrease to dangerous levels. At some point the brain demands a breath, waking the patient. This happens suddenly and with force, so that air is quickly drawn into the lungs. During inhalation, the diaphragm moves upward. During an apneic episode, the force of the upward movement the diaphragm makes gasping for air propels gastric acid up into the esophagus, past the tonsils, burning the tissue and pooling on the teeth, creating recognizable enamel lesions. The pH of these contents is close to battery acid — dramatically worse than the acidic drinks against which we preach ad nauseam.

A word of warning. It will be human nature to adjust your antennas when the patient is obese, and although obese patients are far more likely to be sleep apneics, there is a good number of your patients who do not show the typical signs when first observing them in the reception area. Many thin females display sleep disordered breathing, and they typically have never been screened for SBD or OSA properly by any health practitioner.

Sometimes, the causes for the small garage are iatrogenic in nature. If a person had four bicuspids extracted for orthodontics, he or she has a better chance of a cramped oral cavity. Dr. Bill Hang describes this as having a size 32 tongue and a size 24 space (four bicuspids and four third molars extracted). If the patient wore headgear that forced the maxilla posteriorly, rather than bringing the mandible forward, the airway has a higher chance of being compromised.

Another anatomical variance leading to OSA involves the early growth and development of the patient. This is heavily influenced first by whether or not the patient nursed as a baby and for how long. At Sleep 2007, new research was shown that children who were breast-fed for at least two months as infants had lower rates and less severe measures of a sleep-related breathing disorder, and that breast-feeding beyond two months provided additional benefits for reduced disorder severity.14 It is thought that the action of breastfeeding creates an optimal jaw formation. In the philosophy of minimal intervention, it’s worthwhile to encourage breast-feeding as long as possible.

While on the subject of children, don’t disregard them in the assessments. They suffer from sleep apnea too. Look for the same physical signs as the adults, as well as dark circles under their eyes or that adenoid face where the cheeks are sunken. Ask the mother if the child snores and find out if the child has episodes where the family thinks the snoring is over, then a deep noisy breath resonates throughout the house.

Other symptoms for children with sleep apnea include, not surprisingly, gasping in their sleep, daytime tiredness, hyperactivity/inattentiveness, early morning headaches, poor school performance, lower IQ, and, surprisingly, adult onset diabetes. Keep in mind, however, that many children have sleep-disturbed breathing without snoring at all. This is one way their SBD differs significantly from that seen in adults.

Allergies early in life can cause abnormal breathing patterns, which, in turn, change the craniofacial anatomy, which can then create more breathing problems. There is a battle being waged every waking moment between the masseters and the tongue to keep the maxillary arch stable. As the tongue takes up residence in the lower arch for the mouth breather, it is not providing the defense necessary against the masseteric forces. With no resistance, the masseters win and the maxilla is narrowed. As a result, the palate lifts to form a vaulted shape, and the dominoes continue to fall as the nasal airway gets squeezed from below.

A quick method to check for adequate maxillary width in an adult of European descent is the cotton roll trick as shown in Figure 3. Place one end on the lingual of a maxillary first molar and do likewise with the other. If the cotton roll has to bend to fit, the maxilla may be too narrow. This is not too scientific, but it gives a good idea of how the patient’s maxilla might have been affected early in life.

The next observation is another part of an orthodontic evaluation involving the amount of overbite and overjet the patient exhibits. An overbite in excess of four millimeters is more evidence of a compromised airway, and an excessive overjet can mean an underdeveloped chin or retruded mandible, which also limits airflow by narrowing the pharynx. When craniofacial deficiencies such as these are evident, special attention should be paid to any potential sleep breathing disorder. If the patient can be guided toward myofunctional therapy and orthodontics, he or she can benefit both cosmetically and physiologically.

Now What?

Now that a potential sleep disordered breather is identified, here are a few action plans.

The best course of action would be to already have the dentist interested in the field of sleep, with a team ready to advise the patient. Pass along clinical observations to the dentist, like periodontal and structural concerns, then he or she can lend even more credibility to the discussion. The patient may wonder about a dental interest in sleep, and this is a great opportunity to educate him or her about the appliances available to aid in breathing.

If the dentist does not want to get involved in treating sleep disordered breathing, find another dentist in the area who is interested in taking your referrals. Alternately, a referral to a board-certified sleep physician can be made. If the dentist does not want to get involved at all, at least have the discussion with the patient. Many times, merely planting seeds will stimulate the patient to mention it to his or her own physician.

In Summary

Don’t miss the elephant in the middle of the operatory, but don’t miss the gazelle either. Make a mental list of the signs and symptoms, have the conversation if applicable, or develop a brochure to give patients; then do all you can to get them help. Hygienists are on the front line and establish a consistent, trusting relationship with patients — usually more solid than the dentist/patient relationship. Many times you can save marriages, help patients live more healthy lives, and even save lives. Maybe your patients need a New Year’s resolution — well, you can give them one. To help you get started, you can obtain a copy of an article Dr. Smith wrote for the local newspaper titled “Here’s a New Year’s Goal — Stop Snoring!” by contacting him at the e-mail address below. You can change a few words, sign your name, and send it to your local paper. Whatever you do, let’s spread the word that dentistry cares more about the person than just teeth and gums.

About the Authors

Shirley Gutkowski, RDH, BSDH, has been a practicing dental hygienist since 1986. She is a popular speaker and award-winning author. Gutkowski and Amy Nieves, RDH, are the co-authors of “The Purple Guide: Developing Your Dental Hygiene Career,” a handbook for graduates from dental hygiene school. Gutkowski can be contacted at [email protected].

Kent Smith, DDS, is the co-founder and co-director of the Dental Organization for Sleep Apnea, is on the Medical Advisory Board of Sleep Healers®, and is the course director and instructor for Sleep Breathing Disorders at LVI Global. Contact Dr. Smith at [email protected].

References

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke 2001.

- Longitudinal study of the association between smoking as a periodontitis risk and salivary biomarkers related to periodontitis. Journal of Periodontology. May 15, 2007.

- Pepperell JC, Davies RJ, Stradling JR. Systemic hypertension and obstructive sleep apnoea. Sleep Med Rev 2002; 6:157-173.

- Sleep Mar. 15, 1999; 22(2):217-223.

- Sleep June 1, 2007; 30(6):703-710.

- J Sex Marital Ther. Winter 1995; 21(4):239-247.

- Netzer NC, Eliasson AH, Strohl KP. Women with sleep apnea have lower levels of sex hormones. Sleep and Breathing. Jan. 2003; 7(1):25-29.

- Aloia M, Arnedt J, Smith L, Skrekas J, Stanchina M, Millman R. Examining the construct of depression in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep Medicine 6(2):115-121.

- Phillips BG, Hisel TM, Kato M, Pesek CA, Dyken ME, Narkiewicz K, Somers VK. Recent weight gain in patients with newly diagnosed obstructive sleep apnea. J Hypertens 1999(a); 17:1297–1300.

- Sleep Med Nov. 2002; 3(6):513-515.

- Phillips BG, Hisel TM, Kato M, Pesek CA, Dyken ME, Narkiewicz K, Somers VK. Recent weight gain in patients with newly diagnosed obstructive sleep apnea. J Hypertens 1999(a): 17:1297-1300.

- Obstructive sleep apnea: recognition and management considerations for the aged patient. Advanced Practice in Acute & Critical Care. Acute Care of the Aging Client. Feb. 2002; 13(1):103-113.

- A stepped approach for prediction of obstructive sleep apnea in overtly asymptomatic obese subjects: a hospital based study. Sleep Medicine 5(4):351-357.

- Breast-feeding may help protect against a childhood sleep-related breathing disorder. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 06/11/2007.

Sleep Breathing Disorders

- Sleep Breathing Disorders

Obvious Clinical Signs

- Obesity

- Neck circumference

- Scalloped borders of the tongue

- Enlarged or visible tonsils

- Enlarged uvula

Obvious Signs

- Tiredness

- Inattentiveness

- Falling asleep quickly at night

- Snoring

- Napping

- Coffee/caffeine “addiction”