Red ulcerative lesions: A literature review of “those nonwhite lesions”

Differentiating red ulcerative lesions from other mixed lesions can be challenging for dental professionals. These lesions may have features that resemble white lesions, depending upon the onset of a breakout and when dental examination is sought. Careful review of the medical and dental history can aid in deciding next steps for patients with a lesion of concern.

Oral mucosal ulcerative lesions are described as being small (less than 0.5 cm) or large (more than 0.5 cm), and round or ovoid in shape. Ulcerative-type lesions begin as a red macule1 that ulcerates and is surrounded by an erythematous border. Healing of these lesions produces a yellow-white covering over the deepest parts of the ulcer.

Also by the authors ... What fingernails say about oral-systemic health

The following is a literature review of red ulcerative lesions that are commonly observed in the oral cavity.

Herpes simplex virus infections

Herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) and 10% of herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV-2) oral infections occur in three clinical forms. The most common type consists of small blisters on the lips and are referred to as fever blisters (figure 1). The second type, called primary herpetic stomatitis (figure 2), is usually accompanied by fever, cervical lymphadenitis, and pain. This type of lesion affects the oral mucosal keratinized gingival tissues and mimics gingivitis. The third and least common type presents on the palatal mucosa.

HSV lesions are transmitted by contact with infected individuals. Treatment includes antiviral drugs such as acyclovir and over-the-counter drugs such as Abreva, drugs that aim to decrease the duration of disease and reduce pain.1 Recurrence of HSV is common. It is recommended that dental hygiene procedures during an HSV outbreak be rescheduled until the lesions have healed.

Angular cheilitis

Angular cheilitis is an inflammatory process of the skin at the labial commissure or angle of the mouth (figure 3). It is usually secondary to oral candidiasis, Staphylococcus aureus,1 and systemic conditions that lead to saliva-induced softening of the epithelium.2 Patients with loss of vertical dimension of occlusion, orthodontic appliances, and saliva-producing habits are affected.1 Additionally, individuals with retrognathic malocclusion, removable partial dentures, deepened furrowing of the skin, enlarged lips, nutritional deficiency, weakened immune system, or Down syndrome are at risk of angular cheilitis.2

Management includes antifungal medications such as nystatin placed topically twice per day as a first treatment, as well as protection of the labial commissures with a barrier such as petrolatum jelly or lip balm. Nonhealing lesions should be referred immediately.2

Syphilis

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted disease (STD) caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum. It is transmitted from person to person via direct contact with a syphilitic sore, known as a chancre.3 This is the primary or first of the four stages of syphilis. Oral symptoms during the first stage of infection appear as small red patches on the lips, tip of the tongue, gingiva, or soft palate near the tonsils. These lesions then grow into larger open sores that can be red, yellow, or gray in color.4

Secondary syphilis appears as a rough red rash that can cover the entire body. Untreated syphilis progresses to a latent stage that usually follows secondary syphilis but can occur after primary. Next is tertiary syphilis (figure 4), which is extremely destructive to various organs and may cause large sores (gumma) inside the body or on the skin. When the brain and nervous system are involved, it is called neurosyphilis.

Oral health-care providers can refer patients presenting with lesions for appropriate medical consultation. Penicillin G administered parenterally is the preferred drug for treatment.5

Aphthous ulcers

The aphthous ulcer is the most common ulcerative condition of the oral mucosa. These ulcers present as sores that begin as round, yellowish, elevated lesions that break down into a “punched out” ulcer, which is then covered with a loosely attached whitish, yellow, or grayish membrane. It is surrounded by an erythematous halo on the nonkeratinized oral mucosa (figure 5).6,7

Otherwise known as aphthous stomatitis (or canker sores), the cause of the ulcers is idiopathic and multifactorial, but likely involves activation of the cell-mediated immune system. The ulcers are not caused by acute infections and, therefore, are not contagious.7

Aphthous ulceration is classified into three types6:

- Recurrent minor aphthous ulcer (80%) presents as less than 5 mm in diameter and heals within one to two weeks.

- Major aphthous ulcer (greater than 10 mm) heals within weeks or months and leaves a scar.

- Herpetiform ulcers, which are pinpoint ulcers, heal within a month and are most commonly found on the tongue.

Aphthous ulcers are usually diagnosed clinically alongside the dental history. Locations occur on the nonkeratinized oral mucosae of the labial or buccal surfaces, soft palate, floor of the mouth, ventral or lateral surface of the tongue, tonsillar fossa, free (marginal or unattached) gingiva adjacent to teeth, and alveolar gingiva in the sulci.7

Treatment aims to reduce pain, encourage healing, and prevent recurrence. This includes the use of topical agents such as local anesthetics, coating agents, or occlusive agents. Treatment modalities such as local desiccation, laser therapy, or biopsy are also used.7 Recommendations for dietary supplementation, herbal products, and good oral hygiene are important for healing.

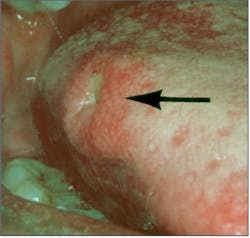

Median rhomboid glossitis

Median rhomboid glossitis (MRG) affects approximately 1% of adults. It has been described as an erythematous candidiasis unique to the midline central area on the dorsal tongue in front of the sulcus terminalis. This lesion has no papillae and is rhomboid in shape (figure 6).8

Usually asymptomatic, antifungal therapy will reduce clinical erythema and inflammation due to candida infection or completely resolve the lesion.9

Identifying variances in normal presentation of oral structures

Dental hygienists and dentists are strategically positioned to identify variances in the normal presentation of the oral structures. Gathering the patient’s medical and dental history at the time of the clinical exam will assist in isolating differential diagnoses for lesions of concern, since the complexity and evolution of red ulcerative lesion breakouts change appearance over time. A periodic review of common lesions will assist the dental team in supporting their patients’ oral and overall health.

Editor's note: This article appeared in the September 2023 print edition of RDH magazine. Dental hygienists in North America are eligible for a complimentary print subscription. Sign up here.

References

- Dunlap CL, Barker BF, Whitt C. A Guide to Common Oral Lesions. Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. UMKC School of Dentistry. https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/read/11603263/a-guide-to-common-oral-lesions-umkc-school-of-dentistry

- Federico JR, Basehore BM, Zito PM. Angular Cheilitis. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. https://www.statpearls.com/point-of-care/32719

- Syphilis. National Institutes of Health. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Reviewed October 27, 2014. https://www.niaid.nih.gov/diseases-conditions/syphilis

- Syphilis oral symptoms. Sexually transmitted diseases and your mouth. Mouthhealthy. American Dental Association. https://www.mouthhealthy.org/all-topics-a-z/sexually-transmitted-diseases

- Syphilis. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. Division of STD Prevention, National Center for HIV, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reviewed May 1, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/syphilis.htm

- Ngan V, Oakley A. Aphthous ulcer. DermNet. January 2016. Updated April 2021. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/aphthous-ulcer

- Plewa MC, Chatterjee K. Aphthous Stomatitis. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. https://www.statpearls.com/point-of-care/17766

- Median rhomboid glossitis. Exodontia.info. https://exodontia.info/median-rhomboid-glossitis

- Goregen M, Miloglu O, Buyukkurt MC, Caglayan F, Aktas AE. Median rhomboid glossitis: a clinical and microbiological study. Eur J Dent. 2011;5(4):367-372.

About the Author

Michele White, DDS

Michele White, DDS, is a general dentist and an assistant professor of restorative dentistry at the UTHealth School of Dentistry where she teaches predoctoral dental students in the preclinic simulation laboratory as well as in the dental clinic. She is the course director for the foundational skills for clinic I and II courses that introduce entry-level dental knowledge and skills to first-year dental students. Dr. White provides dental care to patients in the faculty practice at UT Dentists.

Gary N. Frey, DDS

Gary N. Frey, DDS, is a professor and chair of the department of general practice and dental public health at the UTHealth School of Dentistry.

Updated March 20, 2023

Cleverick “C.D.” Johnson, DDS, MS

Cleverick “C.D.” Johnson, DDS, MS, is a professor and vice chair of the department of general practice and dental public health at UTHealth School of Dentistry.

Updated March 20, 2023

Ben F. Warner, DDS, MD, MS

Ben F. Warner, DDS, MD, MS, is a professor in the department of general practice and dental public health at UTHealth School of Dentistry.

Updated March 20, 2023

Joseph D. Yadin, BS

Joseph D. Yadin, BS, is a graduate of Sam Houston State University. He has a BS in biomedical sciences.

Updated August 4, 2023